The British Army is in a shocking state. It is suffering from the cumulative effect of sustained cuts, chronic underinvestment and lost capabilities. This article explains what the problems are and sets an agenda for renewal and regeneration.

By Nicholas Drummond

Contents

01 – Introduction – An Army in Crisis

02 – How did we let the Army get into this mess?

03 – An Army without a role?

04 – What does the future hold for the Army in terms of likely deployment scenarios?

05 – The British Army’s principal deployment types

06 – The nine Critical issues faced by the Army

07 – Summary

________________________________________________________________________________________

01 – Introduction – An Army in Crisis

Britain’s army is one of its oldest and most respected institutions. With a history that dates back to before the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, no other full-time professional army has done more to protect the interests of the nation it serves. Discipline, courage and tenacity are its hallmarks. The Army’s heritage and tradition have forged a powerful identity that is synonymous with the British national character. It is an organisation that is infinitely greater than any single person within it. Serving within its ranks, even for only a short period of time, is an experience that leaves an indelible mark on all those who wear its uniform. Perhaps its greatest strength is its ability to adapt and evolve when faced with new or unexpected threats.

Historically, Britain has maintained a small peacetime army that is able to expand rapidly in times of war. The British Army’s one major defeat, during the American War of Independence, was largely due to it being too small and unable to grow quickly enough to respond to the rebellion. Today, the number of soldiers in the British Army stands at 76,877[1]This is the lowest level since before the Napoleonic Wars in 1799.[2]Total headcount is 5,603 short of the 82,000 limit set by the 2010 SDSR. According to some former soldiers, the British Army is now engaged in the most important campaign of its long and illustrious existence: the battle for its own survival.

As well as manpower constraints, many vehicles and key weapon systems are approaching a cliff edge of block obsolescence. The FV432 armoured personnel carrier was acquired in the 1960s. The 105mm light gun, SA80 rifle and Challenger 2 main battle tank can trace their roots back to the 1970s. Though there are plans to extend the life of Challenger, including the addition of a 120mm smoothbore gun, there is no disguising its age. The Warrior infantry fighting vehicle and AS90 self-propelled artillery platform were developed in the 1980s. Over half of the combat vehicles in the Army’s inventory are more than 40 years old. To put that in perspective, how often do you see a 40-year old car on the road? Another fact that perfectly articulates the British Army’s decline is that it now has more horses than tanks (540 horses versus 227 Challenger 2 MBTs).[3]Managing to operate with only limited resources has been a British Army strength. Our past performance has been primarily due to excellent training. Since 2010, budgets for maintenance, training and the procurement of new equipment have all been cut or deferred.

Regular Army units are now dependent on Army Reservists to fill manpower gaps when deploying on operations.[4]In theory, the Army is meant to be able deploy at divisional strength. Growing tensions in the Baltic states resulted in the UK contributing troops as part of a multi-national force. Whereas previously we might have sent an entire armoured brigade, we were only able to muster a single battle group at short notice. According to officers who have recently left the service, the Army has less than 40 working Challenger 2 tanks due to the lack of spare parts. The knock-on effect of defence austerity on morale has directly influenced retention and recruitment. The large number of experienced soldiers who have left the service means that accumulated knowledge has been diluted. When strategic, tactical and logistical lessons need to be relearned, inevitably it is a cost that is paid for in blood.

Perhaps cutting the Army to the bone wouldn’t matter if the world was more peaceful. Over the last five years, the geopolitical landscape has become more unstable and volatile than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Russian aggression in Ukraine has re-ignited former Cold War tensions. China is building its armed forces beyond any territorial defence needs. North Korea appears to have abandoned its nuclear weapons programme, but it isn’t clear whether this will lead to Kim Jong Un being deposed by rivals who see him as weak or what might happen if a new regime seized power. Iran remains belligerent towards the West and still has unfulfilled nuclear aspirations. The Middle East remains precarious and unpredictable. Da’esh and the Taliban have yet to be defeated. And, Islamic extremism continues to pose a serious threat at home and abroad.

Despite acknowledged risks and threats, it appears that few people in government understand the implications of a reduced force. Though the Army has become smaller with more limited offensive capabilities, it is still relied upon to achieve significant government policy goals. Fresh deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan have been necessary to ensure security and stability in both regions. As we continue to ask our troops to do more and more with less and less, it is not clear how quickly or decisively we could respond to a major international crisis. Even our most important ally, the USA, has now told us that the Army is too small and needs rebuilding.[5]In short, the time has come to reform and regenerate the Army so that it can properly protect British interests wherever they are threatened.

02 – How did we let the Army get into this mess?

The Army’s decline is not a recent phenomenon. After the Cold War ended in 1989, the bulk of the Army was left in Germany, because we didn’t know what do with it and didn’t have anywhere else to put it. Investment in new land platforms ceased. The Options for Change defence review in 1990 cut manpower from 160,000 men to below 120,000.[6]Since this time the Army has slowly atrophied. The Challenger 2 MBT only arrived after 1998 because Challenger 1 had not fully lived-up to expectations and it took several years before the investment required to improve it to the desired level was finally made.[7]

Ironically, no sooner had the Cold War been declared over than the British Army was dispatched to the Gulf in 1990. As part of the US-led Coalition, Britain deployed an entire armoured division comprised of 53,462 troops. Its mission was to evict Saddam Hussein’s forces from Kuwait in Operation Desert Storm. At the time, senior officers nostalgically remembered when BAOR numbered four complete armoured divisions plus an artillery division. Hundreds of MBTs and IFVs that had remained largely unused for almost half a century were finally allowed to show their mettle. Although the ground war lasted only a matter of days, Coalition Forces performed admirably and Kuwait was liberated with minimal casualties.

The Army was deployed again in 1992 and 1995 to support UN peacekeeping missions in Bosnia. Ongoing stabilisation efforts in the Balkans continued until 2002. Although British troop numbers were much smaller, around 2,400, the deployment (with other NATO allies also contributing ground forces) was successful because it was instrumental in ending a conflict that had raged for years.

In 2000, the Army sent 1,500 troops to Sierra Leone to prevent the capital city, Freetown, falling into the hands of a rebel army. Although a limited deployment, British troops roundly defeated the insurgents to end the country’s civil war. Given the number of troops used and the impact they achieved, the operation was extremely efficient in terms of cost versus effect. Almost 20 years later, it is still viewed as a textbook intervention.

From 2001 to 2005, the Army was deployed to Afghanistan (Phase 1) to bring down the Taliban régime and to attack Al Qaeda strongholds in the region. As a knee-jerk reaction to the 9/11 terror attacks, this operation quickly and effectively achieved well-defined military goals, again with minimal casualties.

In 2002, a second and more controversial deployment to Iraq was initiated by a US-led Coalition force. Operation Telic saw 46,000 British troops take part in the invasion with 179 losing their lives. Claims that Saddam Hussein was 45 minutes from unleashing a nuclear, biological or chemical attack proved to be wide of the mark. No weapons of mass destruction were ever found. Although the goal of régime change was achieved, the unintended destruction of much of Iraq’s infrastructure and the lack of a coherent plan for rebuilding the country afterwards fermented widespread unrest. An operation designed to liberate the Iraqi people ended-up alienating them. The political vacuum that followed and disaffection with the USA and its allies were undoubtedly factors in the rise of Da’esh. With the legality of the Iraq war questioned ever since, the Army’s achievements here are more difficult to quantify.

In 2006, Britain deployed 10,000 soldiers to Afghanistan (Phase 2). UK troops formed a major part of the larger International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF). The aim was to support the nascent Afghan Government by providing security that would help it achieve domestic stability and political independence. The aspiration was to transition control of different regions to Afghan Forces enabling ISAF contingents to withdraw. However, Britain found itself sucked into an intense and protracted counter-insurgency campaign where its forces were regarded as the enemy not a liberator. Some UK commanders believed that the Army was never properly resourced to achieve the tasks asked of it. Others were convinced that the history and geography of the region made any notion winning unrealistic. Mounting casualties eroded home support for a sustained UK involvement. This led to a loss of political commitment and the drawdown of UK forces from Afghanistan that was intended to be complete by 2014. Not surprisingly, leaving before fully achieving our objectives allowed the Taliban to regain control of territory from which they had been dislodged, making the success of Britain’s 12-year Afghan mission, like Iraq, questionable. Some 453 British service men and women lost their lives and more than twice this number suffered life-changing injuries. The British public considers the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan to be over, but according to official Government figures published in July 2018, around 1,000 UK service personnel are deployed in Afghanistan, 1,400 in Iraq, 900 in Estonia, an undisclosed number in Nigeria, Somalia, the Sudan, Gabon and Malawi.[8]

By 2010, when the Coalition Government led by David Cameron came to power, the global financial crisis was in full flood. An overwhelming deficit meant the UK entered a period of unprecedented economic austerity. It was decided that a substantial reduction in UK public expenditure, especially on defence, was necessary to reduce national debt. With no political appetite to deploy British troops, the Army was singled-out for cuts with total headcount reduced from 102,000 to 82,000. It was decided to bring home troops based in Germany. Tank numbers were reduced from 403 to 227.[9]Programs to upgrade and replace key items of equipment were cancelled or postponed. A new expression became commonly used: “capability holiday” which described an army that has essentially been placed into suspended animation. A further defence review in 2015 tried to reconcile the Treasury’s financial strategy with a coherent Military strategy, but the plan focused only on fulfilling roles that were affordable not what was viewed as necessary. In fact, the cuts were so deep and far reaching that any previous Defence priorities that existed were no longer achievable. Despite the announcement of a bold £178 billion equipment plan to invest in new capabilities, new programmes have proceeded at a glacial pace. By July 2017, Former Chief of the Defence Staff, Lord Dannatt, said that the cumulative effect of cuts made to the Army was so severe it risked becoming a Gendarmerie.[10]

03 – An Army without a role?

The domino effect of indeterminate success achieved in Iraq and Afghanistan, the political fallout of casualties, an unwillingness to deploy troops in wars that are seen as “none of the UK’s business”, swingeing cuts to funding, a reduction in headcount, the sustained degradation of our land forces’ war fighting ability, leading ultimately to the undermining of its core roles and purpose the have led people to question the Army’s ongoing relevance to UK defence.

The reality is that when you cut away successive layers of capability, you cannot blame the Army when it is no longer able to perform the tasks you want it to execute. It is also important to remember that a political reluctance to use ground forces is not because they are ineffective – although they may be if their goals are not fixed and there is insufficient political will to support them– it stems from the need for governments to ensure they are re-elected. And there are no votes in Defence. After a decade of austerity, the underlying problem is notthat the Army has an ill-defined role, but that it now lacks the resources it needs to be effective across the mission types that were previously considered to be essential. You cannot blame it for being unfit for purpose when you refuse to allocate the budget that would easily make it so.

Beyond any ill-informed preconceptions about the Army’s role, the Government still relies on it and has quietly re-deployed units to Iraq, Afghanistan and other trouble spots. Although SF and other Army personnel have been involved in local skirmishes, UK soldiers have been operating in advisory and training roles in support of legitimate foreign governments. This evolution in mission reflects a change in policy to avoid casualties more than a change in tactics to achieve strategic goals, but this changed approach is not ineffective, largely because the troops called upon to perform such tasks have adapted themselves well to the job at hand.

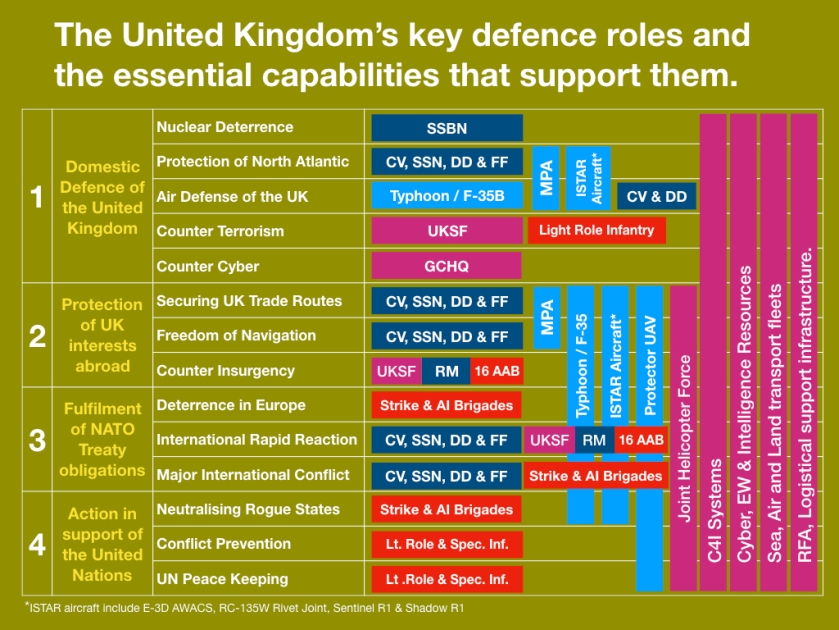

The Army has four well defined overarching roles:

- Domestic Defence of the United Kingdom

- Defence of UK Interests Abroad

- Fulfilment of NATO Treaty Obligations

- Action in Support of the United Nations

These roles a defined by history and geography as much as current policy. Within each, we can expect to perform a wide variety of mission types. The Army operates in partnership with the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. Though potential missions may include a response to natural disasters and other non-military situations where outside intervention is needed, our ability to provide humanitarian air and other support should be a by-product of being equipped for our primary defence roles, not because such missions have assumed a higher priority.

04 – What does the future hold for the Army in terms of likely deployment scenarios?

Looking ahead, the UK Ministry of Defence’s recent policy and doctrinal publication, Future Operating Environment 35,[11]reviews and analyses likely threats and potential deployment scenarios. It is unequivocal in suggesting that the Army still has an essential role to play on an evolved geopolitical stage. A central belief is that all conflicts are still ultimately resolved on the ground. Aircraft and UAVs can degrade an enemy’s ability to wage war, but they cannot seize and hold territory. It means that regardless of how warfare, weapons and tactics evolve, we will still depend on “boots on the ground” to achieve military and political objectives.

Traditionally strategy was developed in terms of Land, Air and Sea domains. More recently Cyber – the information technology and electronic communications domain, has become a priority. Further to this, the USA considers Space as a fifth domain. Using satellites as communication and intelligence gathering hubs can confer a transformational tactical advantage. The ability to protect friendly satellites and destroy enemy ones may become vital in dominating other domains. There is also a sixth domain, which US Army Chief of Staff, General Mark Milley, described as “Headspace.”[12]This is the battle to win hearts and minds. It has always existed, but has increased in importance. More than ever before, knowing what you believe, defining your values and behaviours and then communicating them effectively to those you need to influence achieves a “soft power” effect. In other words, we need to dominate the moral high ground as much as the physical battle space.

The nature of conflict is evolving. Previous wars were characterised by one nation attacking another to achieve territorial or economic gain. Now we see conflict as encompassing ideologies unrelated to geography. We can expect to engage non-state actors as well as state actors. We take the rule of law for granted, but it is becoming easier to subvert rules-based societies. Terrorism and organised crime can overwhelm conventional police forces and governments. Increasingly, our enemies are impossible to distinguish from the local population. Home-grown terrorists, who may be radicalised domestically, rather than those who arrive on our shores from abroad, are a particular problem. As recent terror attacks have shown, we could easily face a situation where large quantities of troops need to be deployed on British streets.[13]

There is a recognition that the distinction between war and peace has become blurred. It is almost as if we live in a state of perpetual conflict where ongoing disputes are never conclusively resolved. Violence flares and subsides requiring constant efforts to monitor and control threats from multiple sources. Cyber attacks may become so serious that they cause infrastructure collapse or even civilian casualties. Formulating an appropriate response may require direct military action as well as a corresponding cyber defence.

Technology is undoubtedly revolutionising warfare. Innovative new weapons, such as drones and directed energy lasers, can achieve an effect out of all proportion to their cost. The increasing sophistication of long-range guided missiles makes warfare less indiscriminate, while the blanket effect of highly potent ICBMs allows states to establish anti-access / area denial (A2/AA) strategies that deter potential aggressors from ever contemplating an attack. Technology continues to revolutionise communications. It can facilitate improved command and control. Remote and automated systems can reduce manpower requirements. Ultimately, exploiting technical innovation can give armies a disruptive tactical advantage. A by-product of technology is that crisis situations can unfold with unexpected speed and severity. It means that more than ever before we go to war with the Army we have not the Army we would ideally like.

The most significant aspects of future conflicts scenarios are demographic and geographic shifts. The world’s population is expected to grow from 7.5 billion today to 10 billion by 2050. With growing concentrations of people living in cities, suburban and littoral areas, future conlficts are most likely to take place across urban environments. The physical control of people in towns and cities requires manpower like never before.

Responding to an evolved future operating environment requires us to embrace innovation, but in many respects the challenge for tomorrow is the same as today: to identify and be prepared to counter the most likely threats without compromising our capacity to deal with less likely threats that have much more serious consequences.

From a practical perspective, there is a recognition that as well as protecting domestic UK territory from internal and external attacks, our Army also needs an expeditionary capability to counter emerging threats at distance before they arrive on our doorstep. Sending troops abroad is not a radical departure from previous UK defence policy. Britain has a long history of expeditionary campaigns that sought to address existential threats at an early stage. Excursions to Sierra Leone and the Falkland Islands show that we excel at short, sharp interventions that nip problems in the bud.

What is less certain is whether we remain capable of mounting significant large-scale operations overseas, as we did during Operation Desert Storm. It remains something we should certainly be able to do and that we would be foolish to pretend is no longer important. We live in an era where alliances and partnerships make vital contributions to world peace. They also imply the military support of friendly nations in the event of an unprovoked attack. A major land deployment in support of European or NATO allies is likely to require the UK to contribute troops to a joint force operating outside the UK. Outside the European Union, the UK can offset the fallout from leaving it by offering military support if needed. Such provision needs to be backed-up with credible forces.

Prior to Russia’s annexation of the Crimea in 2014, peer and near-peer threats were largely viewed as redundant. Russia’s resurgence, evidenced by the extensive rebuilding of its land forces, has raised concerns about its future intentions. Economic sanctions have damaged it and alienated it, making it an enemy. Aggressive posturing and the vulnerability of the neighbouring Baltic States makes Russia a real and present danger.

Opportunistic Iran could easily flex its muscles to settle longstanding differences with Saudi Arabia and Israel. The situation in Syria continues to deteriorate. With Islamic extremists fighting the despotic Assad régime in Syria, it is hard to distinguish friend from foe. The situations in Yemen, Egypt, and Libya are also problematic and could easily escalate without warning. Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, with Turkey aligning itself with Qatar, add further levels of complexity and risk to the region.

Instability and terrorist extremism in Africa continue to undermine legitimate governments and the rule of law. Any of several Commonwealth countries could be targeted and might call upon the UK for military assistance. We could easily find ourselves involved in a situation similar to Sierra Leone or Mali. Widespread criminal activity among gangs motivated by economic gain more than religious ideology has created humanitarian crises. Such suffering demands a response.

China clearly intends to become a global superpower as well as dominating the Pacific region. While it poses no immediate threat, it is using its economic might to build forces that rival those of the United States. Cold War 2.0 is more about China than Russia. The risk is that China could ally itself with a state that poses a direct threat to NATO.

While the threat of North Korea appears to have subsided, there is a view among regional experts that Kim Jong Un cannot cease developing nuclear weapons, because he may be perceived by his rivals as being weak. Therefore, there is the risk of him being deposed or continuing to develop nuclear weapons clandestinely. North Korea’s frequently-stated long-term objective is the re-unification of North and South. If it plans to do this through the use of force, then it needs to lay the foundations of an Anti-Access / Area Denial strategy that would prevent anyone from countering an invasion of South Korea. While a conflict on the Korean Peninsula would likely involve China and Japan, it would not be directly relevant to United Kingdom interests (although 81,000 British troops were deployed between 1950 and 1953 during the previous Korean War). It is also worth noting that a war in Asia could be used as a catalyst by other potential adversaries. With the USA distracted by an Asian campaign, Russia or Iran, for example, could independently act to secure their own political or military agendas elsewhere.

Ultimately, we may wish to assume that a high intensity conflict against a peer enemy is unlikely. We can only ensure that this remains so through the building potent forces with an ample deterrent effect. We forget at our peril that the peace we have enjoyed in Europe since 1945 is based on parity of strength. The token force presently deployed in Estonia may not be sufficiently credible to deter Russian aggression. If Russia’s President Putin thinks he can conquer the Baltic States without a fight he may well try his luck. Though we possess nuclear weapons, if Russian forces had already seized territory in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, we would be reluctant to respond with either tactical or strategic nuclear weapons after the fact, just as we failed to respond militarily after Russia annexed Ukraine territory. Prevention is invariably better than cure. Credible land forces that serve to hold ground achieve a worthwhile deterrent effect. Moreover, it is far better to respond to a ground attack with conventional weapons that force a withdrawal, rather than having no recourse other than a nuclear response. If land forces fail to deter or repel, they may still buy negotiating time before the use of nuclear weapons becomes inevitable.

Building an army that sufficiently strong to have a deterrent effect may be perceived as an expensive insurance policy. But, given the evolution of long-range missiles and other complex weapons there is no need to return to Cold War levels and re-create a large standing army. However, we do need a minimum amount of troops organised to operate independently or in partnership with other NATO or European allies. The current state of the British Army is evidence that we are well below a minimum land power threshold.

05 – The British Army’s principal deployment types

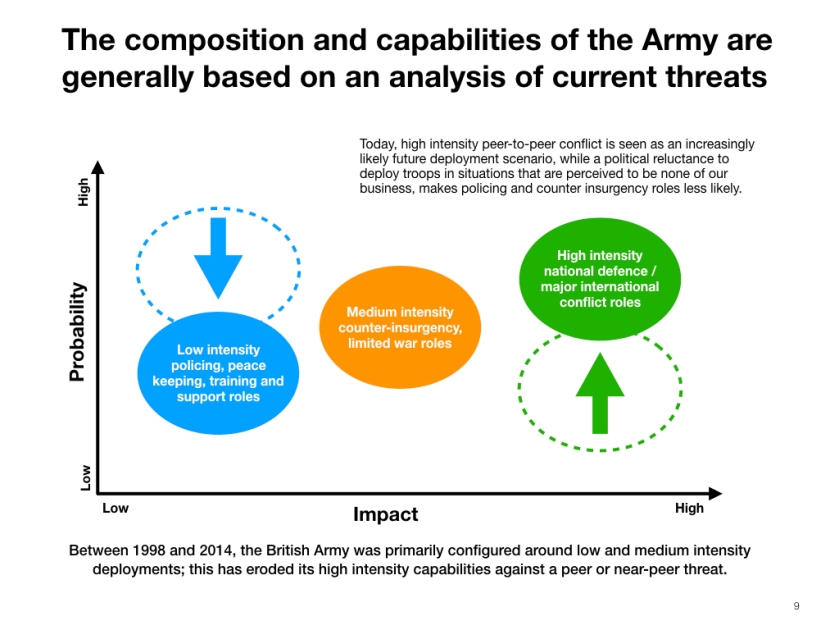

The above threat scenarios and the risks they describe translate into four British Army deployment types:

- High intensity warfare against peer or near-peer threats

- Medium intensity limited operations against medium level conventional / asymmetric threat

- Low intensity interventions against low level rebel forces / criminal gangs

- Peace support, policing, training and aid distribution

As a general rule of thumb, if the Army is resourced to counter the most serious and potent threats, it should easily be able to adapt downwards to respond to less intense scenarios. A historical aspect of equipping any army to respond across a wide variety of mission types is that the next deployment is seldom like the last one. This implies a set of general purpose capabilities.

Traditionally, the Army has been focused on operations that required the use of heavy armour. While tanks and IFVs are still relevant to high intensity operations against peer enemies, such assets are increasingly less ideal when used in other roles. This is partly due to the fact that future operations are expected to be focused on urban, littoral and other complex terrains rather than wide open spaces conducive to armoured warfare.[14]Whatever future operating environment the Army finds itself in, the “iron triangle” of Firepower, Mobilityand Protectionwill need to be balanced to ensure not only vehicles but entire formations can manoeuvre to deliver effect. New capabilities will need to be incorporated into system design to maximise functionality and efficiency. Connectivity is ensuringeffective communication through systems that allow information to be securely shared via voice and data. Harnessing the power of fully-networked units will also facilitate more effective command and control. Sustainabilityis configuring systems and processes that contribute to a reduced logistical footprint and the ability of units of varying size to operate independently and at distance. Perhaps the most important element of all is Adaptability, which is building-in flexibility to allow weapons, vehicles and support systems to be easily reconfigured to perform different battlefield roles and mission types.

In rebuilding the Army, we need to identify specific concerns and prioritise remedial actions that will ensure it is fit for purpose. These are as follows:

06 – Critical issues faced by the Army

Critical issue 1 – Manpower

Presently the size of the Army only allows the UK to field a single division with four brigades plus a further independent air assault brigade. Increasing manpower to 92,000 from its present size would allow two divisions with three brigades each, plus an air assault brigade, to be generated. Theoretically, we could form two full divisions from current manpower levels, but the second would not have the necessary supporting units to deploy independently.

An Army of 92,000 would allow additional infantry, cavalry and artillery units to be recruited, but also engineers, logistical elements, C4I, and other assets essential to ensure a robust overall structure. This level of manpower would provide a larger pool of soldiers from which to select Special Forces personnel. It would also ensure a sufficient number of troops to fulfil other permanently committed forces obligations. It would establish regular reserve forces capable of reinforcing the two primary divisions in time of war. Such a structure would allow the Army Reserve to be correctly focused on rapidly expanding the Regular Army into a third and fourth division should the need arise.

At the moment, Regular Army units can only train properly when additional manpower from the Army Reserve is attached to them. This is far from ideal in terms of effective integration, training standards and levels of readiness. Large formations operate with maximum efficiency when the soldiers within component units spend time training together. Units thrown together at the last minute cannot be expected to exhibit the same levels of discipline, cohesion and combat capability.

Critical issue 2 – Mobility

One of the most important future operational success factors is mobility.How the army gets to the fight is likely to be as challenging as the fight itself.

Resourcing the Army so that it is effective across the deployment scenarios identified above will require it to invest in vehicles and other modes of transport that give it three types of mobility:

- Strategic mobility– how a force deploys from its country of origin to the theatre of operations

- Operational mobility– how a force deploys from its theatre entry point to area of combat operations

- Tactical mobility– how a force moves within the battle space including fire and manoeuvre.

In many scenarios, MBTs and IFVs will be too heavy to deploy quickly or too inflexible to respond to certain operational tempos. However, the need for protected mobility to deliver troops wherever they are needed – the requirement for armoured personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles– remains constant. There is a corresponding need for protected firepowerto neutralise other armoured vehicles and support dismounted infantry- the requirement for direct fire support vehicles or tanks– also remains constant. That said, the evolving nature of likely future operating environments highlights the need for more flexible vehicles with greater mobility.

Wheeled vehicles offer good on-road performance for operational mobility. Since they are less mechanically complex than tracked vehicles, they are more reliable and require less maintenance. This means units equipped with them have a smaller logistical footprint and can operate with greater independence at distance. This is ideal for expeditionary roles. The barrier to wheeled vehicle adoption has always been off-road performance, but the latest generation of 8x8s, 6x6s and 4x4s perform well in soft soil conditions, offering substantially improved tactical mobility. As wheeled vehicles have improved, so the need for tracked vehicles can be scaled back. However, for heavier vehicles above 40 tonnes, tracked platforms may still be preferable as they offer greater stability for mounting larger weapons.[15]They also retain a tactical mobility edge when operating in the most challenging terrains.

The US Army fulfilled its rapid reaction mobility requirement via the Stryker Brigade concept. This led to the adoption of the an 8×8 family of vehicles from 2002. Since then, Canada, Australia, Germany, France, Italy, Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Austria, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Switzerland, Spain, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, South Korea and Japan have all adopted medium weight wheeled vehicles to complement traditional heavy armour. So have Russia and China. The UK identified the same requirement in 1998, but twenty years later, the British Army still does not possess such a capability.

Helicopters have become important too. Here Britain has invested in a sizeable CH-47 Chinook fleet. Operated by the RAF, it allows the rapid movement of troops and supporting materiel by air. Attack helicopters have proved to be particularly useful across a variety of terrains and combat mission types. With an excellent ability to defeat MBTs in peer conflicts, they are also relevant to medium and low intensity operations. The ability of helicopters to look down, observe and engage targets from stand-off ranges has proved invaluable during recent conflicts. The Army also possesses the Lynx Wildcat utility helicopter but has too few to airlift a sizeable force. The RAF additionally operates the Puma support helicopter. Although this has an acceptable payload capacity, it dates back to the 1970s. Puma needs to be replaced by a single large utility helicopter, ideally operated by the Army.

In terms of strategic mobility, the Army is well supported by the RAF’s fleet of 8 Boeing C-17A Globemaster strategic transport aircraft, which can carry up 80 tonnes of cargo. It will soon have 22 Airbus A400M Atlas tactical transport aircraft which can carry up to 33 tonnes of cargo, plus 25 Lockheed C-130J Hercules tactical transport aircraft which can carry 20 tonnes of cargo. In most situations, the UK would deploy a brigade-size unit by sea. However, having the capacity to deploy a single 8×8 MIV or 4×4 Foxhound battle group by air could be a crucial advantage when time is of the essence.

Critical issue 3 – Vehicles, weapons and equipment

The major problem with all army combat vehicle platforms is a lack of numbers. Under the Army 2020 Refine plan, it is anticipated that there will be just two regular and one reserve tank regiments with the total number MBTs reduced further from 227 to just 168. Similarly, there will only be 380 upgraded Warrior IFVs from an original total of 789, but only 245 of these will have the new 40mm CTA cannon. With the Ajax reconnaissance vehicle, a total of 589 will be acquired, but only 245 of these will mount a 40mm CTA cannon.[16]

The Challenger 2 main battle tank Life Extension Programme (LEP) must remain a priority, but needs to include a new main armament to replace the existing 120 mm rifled gun, which is approaching obsolescence. The Army is considering the Rheinmetall 20mm L/44 and120mm L/55 smoothbore guns, both which fire more advanced ammunition natures and which would give us commonality with our NATO allies, including the US Army. The Challenger 2 drivetrain also needs upgrading. With so much that needs to be done to maintain Challenger 2’s effectiveness, we ought to consider whether replacing it with an alternative MBT design would be more effective and less costly.

The new Ajax combat reconnaissance vehicle is a much anticipated replacement for the CVR(T) family, but prioritising its introduction over new MBTs and IFVs is unfortunate because updated versions of Challenger 2 and Warrior are more urgently needed. We presently plan to acquire 589 Ajax variants of which 245 will be turreted reconnaissance variants. Ajax mounts a new 40mm cased-telescoped cannon, this is a significant step-up from the legacy Rarden 30mm cannon.

The Warrior infantry fighting vehicle was meant to be upgraded via a Capability Sustainment Programme (CSP), but more than a decade since being initiated it has yet to deliver. There are ongoing issues with the Lockheed-Martin turret, while cost growth may impact affordability. The CSP will not address serious concerns with the hull of vehicle identified after several Warriors were lost in Iraq and Afghanistan. In particular ammunition stowage in the crew compartment, bulkhead and hatch design, location of the fuel tank beneath the turret and underbody protection create serious survivability issues. This is evidence to suggest that this programme should be abandoned and either the Ajax or Boxer IFV should be acquired instead.

The Mechanised Infantry Vehicle Programme is the Army’s most important combat vehicle priority to replace the FV432 armoured personnel carrier, acquired in 1963 and to provide an expeditionary capability. The ARTEC Boxer is a superb vehicle and was selected to fulfil this requirement in 2018. It is expected to provide the Army with a class-leading medium weight 8×8 capability. The only concern is whether we will acquire sufficient numbers to fully replace the FV432 APC.

The Army desperately needs new and upgraded artillery systems. In particular, the 105mm light gun, and 155mm AS90 howitzer have reached the limit of their development potential. There is a pressing need for a new self-propelled 155mm L/52 howitzer. Although the Army recognises this, and a new Mobile Fires Platform programme has been initiated, no funding has yet been allocated. The Guided Multi Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) continues to be an excellent system, but the M270 tracked platform which launches the rockets is now old and needseither to be upgraded or replaced.

Across the entire combat vehicle fleet, the Army needs more wheeled platforms for protected mobility and enhanced deployability. The Multi-Role Vehicle Protected (MRV-P) Programme will replace a number of legacy MRAP platforms with two types. The MRV-P Package 1 vehicle will replace the Panther Command & Liaison Vehicle and the Husky Tactical Support Vehicle with a single type. As things stand, it is planned that the Oshkosh JLTV will be acquired, which has been selected by the US Army. Unfortunately, the JLTV has internal space issues and cannot easily accommodate Bowman communication equipment. Moreover, costs are reported to have risen substantially, undermining the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) case for purchasing the vehicle without a competition. As things stand, there is a danger of paying a premium to purchase a sub-optimal vehicle. The MRV-P Package 2 vehicle will replace the Land-Rover Battlefield Ambulance and Mastiff MRAP with an armoured ambulance and troop carrying vehicle. This is expected to be either the Thales Bushmaster (which is already in service with UK Special Forces) or the General Dynamics Eagle. Both seem adequate for the intended roles.

The recent decision to upgrade the Apache AH-64 attack helicopter fleet to the Block E standard is a welcome initiative that will maintain an important capability. However, the reduction in fleet size to just 50 helicopters compromises the previous corresponding reduction in main battle tanks when Apache was originally acquired. The Army plans to replace its Gazelle helicopter fleet with a new light reconnaissance and liaison helicopter. Presently, the RAF provides a support helicopter capability via the Puma HC2. However, this is extremely old and it only has 24. Although the Chinook fleet is considerably larger with 60 rotorcraft, the Army needs more tactical transport helicopters. Replacing Puma and Wildcat with a single helicopter type operated by the Army or RAF, might be a more efficient means of transporting Air Assault Brigade elements.

The Javelin anti-tank missile is highly effective, but is likely to be rendered obsolete when Russia fields the T-14 Armata and T-15 IFV. Its out-of-service date is 2025. The MBDA MMP could be an ideal replacement especially as missile costs are expected to be at least 30% lower than Javelin. For the long-range ATGM requirement, the UK never replaced its previous vehicle-mounted system, Swingfire. Instead, Hellfire was purchased for use by Apache attack helicopters. More recently, Spike NLOS was purchased on a limited basis to provide a long-range (25 km) precision capability. This is an excellent system needs to be fielded more widely or substituted by a long-range precision fires missile system. Something like a ground-launched Brimstone missile has been proposed by MBDA and would be ideal for engaging a range of targets, including armour. The Army also needs a Deep Fires Missile capability. This would be a 300-499 km range missile similar to the US Army’s ATACMS / DeepStrike systems. In terms of anti-aircraft systems, the Army needs to adopt the Medium Range Sky Sabre missile system more widely. The current Starstreak HVM is an excellent system, but the Stormer platform needs upgrading. Mounting Starstreak on a wheeled platform such as Boxer would be ideal.

The Army’s small arms are also showing their age. Infantry rifles and machine guns remain the basic building blocks of military capability. The L85A2 is being upgraded to A3 standard, but it is likely that the US Army will adopt a new small arms technology including a new caliber from 2020. If this happens, the UK may wish to adopt it too, especially if it promises to simplify logistics while providing increased range and lethality.

Last, but by no means least, the Army’s C4I systems facilitate effective command control, communication (voice and data), and computer information. Replacing the Bowman system with Morpheus (LEtacCIS) is ongoing and funded. Investment in this area must continue to ensure that communications over long and short distances are secure and reliable. Future solutions will need to address cyber warfare, electronic warfare (intercepting and jamming enemy communications) and the hardening of systems against attack.

In summary, the British Army’s combat capability is provided by a comprehensive range of weapon system types.[17]The list below is not exhaustive but includes the most important. Those marked in bold red italic need replacing or upgrading:

A. Combat Vehicles

Challenger 2 Main Battle Tank / 120mm gun

Ajax Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle / 40mm cannon (replaces CVR(T))

Warrior Infantry Fighting Vehicle / 30mm cannon

Boxer MIV Vehicle (replaces FV432) / 12.7mm HMG

B. Artillery Platforms

AS90 155 mm SP howitzer

L118 105 mm towed howitzer

G/MLRS SP artillery system

Mamba Counter Battery Radar

Watchkeeper ISTAR Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

Sky Sabre / Land Ceptor / CAMM Ground-based Medium-range Air Defence System

Stormer / Starstreak HVM Short-range Air Defence System

C. Protected Patrol Vehicles*

Multi-Role Vehicle Protected – Bushmaster TCV & PBFA

Multi-Role Vehicle Protected – JLTV CLV & TSV

Jackal / Coyote LPV

BVS10 – All-terrain vehicle

D. Helicopters

Boeing Apache AH-64E Attack Helicopter

AW159 Lynx Wildcat Utility Helicopter

Aérospatiale SA341 Gazelle

Britten-Norman Islander AL1 / Defender AL2

E. Engineer Vehicles

Terrier Combat Engineer Vehicle

Trojan AVRE Armoured Engineer Vehicle (based on Challenger platform)

Titan Armoured Bridgelayer (based on Challenger platform)

CRARRV Challenger Armoured Repair & Recovery Vehicle (based on Challenger platform)

JCB 4CX HMEE Armoured Backhoe Excavator

Buffalo Counter-IED MRAP vehicle

Alvis Unipower Tank Bridge Transporter Vehicle

M3 Amphibious Rig Amphibious Bridge Vehicle

F. Other Engineer & Logistic Support Vehicles

Oshkosh HET Heavy Equipment Transporter

Oshkosh MTRV Close Support Tanker

MAN HX SV Support & Cargo Vehicle

MAN SX SV Enhanced Palletized Load System (replaces Leyland DAF/ Foden DROPS)

Land-Rover Battlefield Ambulance

Land-Rover Wolf 110 Utility Vehicle

Yamaha Grizzly Quad bike

G. Infantry Small Arms

L85A2 / A3 5.56mm Assault Rifle

L7 A2 / A3 7.62mm General Purpose Machine Gun

L129A1 7.62mm Sharpshooter rifle

L115A3 8.59mm Precision rifle

L131A1 Glock 17 Gen 4 9mm Pistol

H. Infantry Support Weapons

L111A1 12.7mm Heavy Machine Gun

L123A2 40mm LV Underslung Grenade Launcher

L134A1 40mm HV Grenade Machine Gun

L16A2 81mm Mortar

FGM 148 Javelin Anti-tank Guided Weapon

NLAW Anti-tank Guided Weapon

L2A1 Anti-structure Munition

Starstreak HVM MANPAD

I. Infantry Explosive Weapons

L109A1 Fragmentation Grenade

L84 White Phosphorous Grenade

L132A1 Smoke Grenade

M18 Claymore Remote Control Anti-personnel Directional Mine

L9A8 Bar Anti-tank mine

J. Communications Equipment

Falcon Joint Tactical Trunk Communications System

Bowman Tactical Voice & Data Communications System

Reacher / Talon / Skynet5 Satellite Communications System

Critical issue 4 – Infrastructure

One factor driving the reduction in force size was knowing where to put different units returning from Germany. The Army needs to invest in new UK facilities to house regiments and battalions. This includes building more modern barracks, training facilities, logistics centres, equipment storage depots, shooting ranges, married quarters, hospitals, schools, and all of the supporting services necessary for an army to function efficiently. Much of the land and property on the MoD’s books needs renovating. The cost of doing so has been postponed for more than a decade. While much infrastructure is now well below the expected standard, the quality of facilities available to soldiers directly influences morale and retention.

An effective approach has been the creation of garrison centres that concentrate forces to avoid unnecessary duplication of infrastructure. These include Aldershot, Tidworth, Colchester, Catterick and units based adjacent to Salisbury Plain Training Area (Warminster, Upavon, and Bulford). The Army possesses many independent barracks that are old and ill-equipped. There are already plans to dispose of these and re-base units in new military centres. This will save money as well as driving efficiency.

An important question that needs to be asked is whether the Army needs to bring all units serving in Germany back to the UK. There is a strong case for leaving a single armoured brigade plus divisional artillery, engineer and logistic assets in Germany. Occupying a single garrison centre, e.g. in the Paderborn area, could be ideal as there are many existing facilities. If this is not affordable, could establish a new permanent European base in Poland or the Baltic States.

We also need to consider whether the Army needs other overseas bases, e.g. in the Middle East. The new Naval base in Oman could also be used by the Army as logistics hub for Middle East or African deployments.

Critical issue 5 – Training

A less obvious aspect of budget cuts is that there is less money for training. There is no point in rebuilding existing capabilities or acquiring new ones unless adequate resources are allocated for units to train with new equipment and weapons. This includes training outside the UK, training with allies and the provision of training ammunition supplies.

The UK maintains an armoured training facility in Canada at Suffield. It also has access to European facilities in Germany and Poland. Such facilities are focused around traditional armoured warfare, so it may be necessary to re-think what kind of facilities are needed given likely future deployment scenarios.

Critical issue 6 – Communications / C4I

Good communication systems are a force multiplier because they facilitate improved command and control. Fully networked formations that are able to share data reliably and securely between units will develop a much clearer picture of an evolving tactical situation. This makes the choice and management of communication systems vital. The forthcoming replacement of the Bowman system by Morpheus (LETacCIS) should substantially improve the Army’s combat communications and general C4I capabilities. However, the lifetime of all such systems is inevitably short given technology lifecycles. Constant efforts are required to identify future needs and systems that meet them. Cyber warfare is an integral and growing component of this. How we protect C4I systems against interception, jamming and electronic / electromagnetic threats will be a major concern. Part of this is ensuring that field headquarters are suitably equipped and can be rapidly established and moved.

Critical issue 7 – Logistics

Addressing logistical challenges remains extremely important to ensure that units of varying sizes can deploy at distance quickly and remain effective in the field. As with communications, we can harness technology to reduce the logistical burden of units in the field and to ensure “just in time” delivery of key supplies and ammunition.

One of the problems of acquiring a variety of UOR vehicles rapidly is platform profusion. Presently the Army has 10 different protected patrol vehicles: RWMIK Land-Rover, Snatch 2 Land-Rover, Foxhound, Mastiff, Ridgeback, Wolfhound, Jackal, Panther, Pinzgauer, and Husky. For MRV-P[18]the Army is planning to acquire two vehicles: the US JLTV 4×4 and a further 6×6 PPV. If both can reduce the total number of platforms, it will aid logistical efficiency, reduce costs and speed field deployments.

The Army needs a massive logistics chain to manage delivery of munitions and key resources when forces are deployed on operations. It needs up-to-date computerised systems to manage inventories and ensure on-time deliveries. Automated logistics also saves manpower.

Critical issue 8 – Recruitment and Retention

When the UK Secretary of State for War, Edward Cardwell, instituted his army reforms between 1868 and 1874, British Army life was not much better than penal servitude. Today, the quality of life is much improved, but the Army’s attractiveness as a career choice or a career that opens doors to other careers after a period of service has diminished.

The key to attracting high quality recruits is obviously pay and conditions, but also positioning the Army as a door-opener to other career opportunities after a soldier’s military service is complete. Education that helps soldiers of all ranks develop their potential and to achieve high technical standards in performance of their military tasks can only benefit the Army, especially as weapons become more sophisticated and complex. Educational attainment must be backed-up with valid qualifications that employers outside the Army value. Education is also important for retention, especially when it facilitates promotion and career development.

An important factor that encourages soldiers to stay is a sense of belonging to professional organisation which is highly regarded by others. The Army’s reputation and tradition instil a sense of pride and camaraderie that few other professional organisations enjoy. But if the Army is diminished in the eyes of those who would join it or who already serve within it, it will lose its attraction. This can become a downward spiral that leads to a loss of morale, an exodus of experienced soldiers, lost capability and a diminished army.

General Sir Nicholas Carter, Chief of the Defence Staff, commented that the public perception of the Army reflects sympathy not empathy.[19]This may reflect a lack of support for recent conflicts the Army has been involved in given the results achieved and casualties sustained. Whatever the reason, it suggests that the Army is no longer a great career choice.

So, we must rebuild a positive perception of the Army by genuinely making it a good career choice as well as a force fully capable of securing UK interests. This is fundamentally about building and maintaining morale and a sense of organisational cohesion.

Critical issue 9 – The need for smart procurement and through life support

More than enough ink has been spilled on this subject, so it is only included here for the sake of completeness. However, it needs to be said that the Army’s record for procurement, especially of vehicles, hardly reflects best practice. When procurement is done badly, it will need to be repeated. The saga that describes the sorry introduction and performance in battle of the L85A1 SA80 assault rifle led to a stream of changes before it was finally redesigned in 2002 – some 16 years after it entered service.[20]It is one of the most expensive rifles ever adopted by any army without necessarily being the best. The failure of the FRES programme to deliver an 8×8 armoured personnel carrier is another case in point. The need to drive increased efficiency in this area will reduce the cost to run the Army, making the benefits it provides easier to justify.

Despite mistakes, there are many equipment highlights. The FV432 acquired in the 1960s, has been a workhorse for the Army. The 105 mm light gun and 81 mm mortar have also been exceptional weapons. The Challenger tank when it first arrived was a world-beater. The CVR(T) reconnaissance family was also a great success. We have shown we can get procurement right before; we can do so again in the future.

06 – Summary

Back in the mid-1990s, Britain’s post-Cold War Army had already begun to think about its future role and the capabilities it would need to counter existential and emerging threats. Any aspirations that existed before 2010 were massively reduced in size and scope by the defence review and subsequent cuts to funding. The piecemeal allocation of budget ever since may have hamstrung the Army’s ability to think big.

Efforts to rebuild the UK Army need to be underpinned by a revised strategy that tightly defines its roles, resources and funding requirements. This cannot be driven by the Treasury’s financial goals. Defence is not simply a line item in government expenditure, it is about protection in the purest sense.

After a decade of austerity, the Army needs reforms that are as far reaching as Cardwell’s or Haldane’s. Between 1906 and 1912, the UK Secretary of State for War, Richard Haldane codified the learnings of the Boer War by introducing new doctrines, structures and equipment.[21]The major element of his plan was the creation of a fully-functional peacetime expeditionary force. This was trained and equipped to serve overseas with a full complement of supporting elements. It established a Territorial and Volunteer Reserve force that would facilitate rapid expansion in time of war. When the First World War begun a few years later, Haldane’s foresight allowed Britain to deploy the best equipped and best trained army we had ever assembled.

Today, Britain’s army continues to be comprised of well-led, high quality soldiers. But it has not received a full-scale overhaul since the end of the Cold War. If we question its relevance, it is because so much of its equipment and doctrine are out-of-date. The time has become to invest in the Army, so that it is capable of performing everything we expect of it.

______________________________________

Notes:

[1]UK Ministry of Defence, July 2018

[2]UK Ministry of Defence, July 2017

[3]UK Parliament, Daily Hansard, 20 July 2013

[4]UK Infantry battalions lack third platoon each rifle company, this would be made-up from Army Reserve soldiers in case of deployment and was an outcome of the 2010 SDSR

[5]General Mark Milley, US Army Chief of Staff, RUSI Land Warfare Conference address, June 2017

[6]Defence Options For Change, UK MoD, July 1990

[7]Challenger 2 Main Battle Tank 1987–2006, By Simon Dunston, New Vanguard Series – Osprey Publishing, May 2006

[8]UK Ministry of Defence 11 July 2018, plus UK Armed Forces Personnel Deployments as at 1 April 2017, UK Ministry of Defence.

[9]Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty, Strategic Defence & Security Review, UK MoD, October 2010

[10]General Lord Richard Dannatt quoted in the Daily Telegraph, July 2017

[11]Strategic Trends Programme, Future Operating Environment 35, UK MoD Official Publication, August 2015

[12]General Mark Milley, US Army Chief of Staff, RUSI Land Warfare Conference address, June 2017

[13]Operation Temperer, July 2017

[14]Strategic Trends Programme, Future Operating Environment 35, UK MoD Official Publication, August 2015

[15]The view of Patria Land Systems, Finland, manufacturer of the 8×8 Armoured ModularVehicle (AMV).

[16]General Dynamics UK, manufacturer of the Ajax combat vehicle

[17]Source: MoD, British Army

[18]British Army website

[19]General Sir Nicholas Carter, Chief of the General Staff, quoted in the Daily Telegraph, 8 July 2017

[20]The Last Enfield, SA80 – The Reluctant Rifle, Steve Raw, Collector’s Grade Books, November 2003

[21]The Edwardian Army: Manning, Training, and Deploying the British Army, 1902-1914, Timothy Bowman / Mark Connelly, Oxford University Press, May 2012

Well, that is a hugely impressive piece of writing. You appear to have an encyclopedic knowledge of the British Army: its history, its traditions, its people, it equipment and very importantly, the reasons for its current decline. I shall probably have to read it a couple more times before I am able to ask a really relevant question.

However, here goes with the first attempt. Recently you published on you Twitter a list of the UK’s most important defence roles: Domestic Defence of the UK: Protection of the North Atlantic; Securing key trade routes; Defence of UK Trade routes abroad; Protection of the North Atlantic; Counter Terrorism; International Rapid Reaction; Cyber Defence, etc. etc. etc.

If there were (Heaven forbid) to be more cuts, including some to the Army, do you have any views at all on which of those roles could possibly be abandoned or diminished? I personally can’t see one!

On a more mundane note, you mention at one point in the article, that “Many of the weapons listed above are obsolete or need upgrading. In particular the 105mm light gun, 120mm rifled tank gun, and 155mm AS90 howitzer have reached the limit of their development potential.” I would agree on the first two items but couldn’t the AS90 be upgraded by installing the Braveheart system, with new barrel? Surely many pieces of current equipment could be upgraded in similar fashion and our Armoured Brigades would have a sound basis in Challenger 2, Ajax, Warrior 40mmm, ABSV, etc. etc. It is the question of the Warrior upgrade which really worries me. There has been a spate of rumours concerning its upgrade to the 40mm cannon recently, about possible reduction to the contract or even, cancellation altogether! If the latter were to happen, where would that leave our Armoured force? Just having to run on the 30mm Rarden version for another 15 years or something? We can’t simply just manage without an infantry fighting vehicle!

LikeLike

Mike,

Thank you for your kind words.

To answer your points. I honestly don’t think we can reduce our Defence roles and capabilities any further. My list of 10 key missions cannot be pared back without seriously compromising our ability to respond to an unexpected global crisis. While the roles should remain constant, we could reconsider the capabilities that fulfil them. The carriers and the F-35 aircraft that fly from them are often singled-out as being the most costly capabilities. If we’d acquired the carriers for £2 billion each instead of £4 billion, they’d be very good value indeed. We certainly need carriers and I wouldn’t like to see them cut, (nor our amphibious capability). The biggest problem we have is the cost of the F-35B and how this has been increased by a weak pound. It seems likely that we will reduce the total buy of F-35s from 138 to under 100.

As for 155mm SPGs, the Braveheart solution would be very good, no question about that, but we probably need new AS90 hulls. I also like the German Pz 2000 and South Korean K9.

The Warrior upgrade worries me greatly too. Lockheed Martin has done a good job with the turret and mission systems fit. They’ve turned Warrior into a brand new vehicle. But I do think it is a scandal that the WCSP budget doesn’t include relocating the fuel tank from the floor under the turret to the rear exterior of the vehicle. it means that it is unlikely to achieve Level 4 blast protection. I’d like to see the UK buy either the Ajax IFV or CV90, both with Lockheed Martin’s 40 mm turret. Whatever we do, we absolutely need a tracked IFV.

LikeLike

Many thanks for the reply. You appear to have dealt with my questions very comprehensively and satisfactorily.

I wanted to ask another question. You mention at one point how various scenarios and risks translate into four roles for the British Army, including: High intensity warfare against peer or near-peer threats and Medium intensity limited operations against medium level conventional / asymmetric threat. You also state how, if we build powerful enough deterrent forces, “Ultimately, we may wish to assume that a high intensity conflict against a peer enemy is unlikely.” Let us assume that latter to be the case, perhaps a dangerous assumption, but nevertheless medium intensity limited operations against medium level conventional threats seems a more likely eventuality.

You further mention that “A historical aspect of equipping any army to respond across a wide variety of mission types is that the next deployment is seldom like the last one. This implies some kind of general purpose capability.” Linking this with a further statement that:

“Large formations operate with maximum efficiency when the soldiers within component units spend time training together. Units thrown together at the last minute cannot be expected to exhibit the same levels of discipline, cohesion and combat capability”, I was wondering whether you would consider that the idea of returning to the idea of multi-purpose brigades might be the solution for the greater part of the British Army.

Under the heading of Adaptability, you point out the need for “building-in flexibility to allow weapons, vehicles and support systems to be easily reconfigured to perform different battlefield roles and mission types”. I was thinking of a simple example concerning the RG35, which, as you know, is a wheeled vehicle designed as a hybrid, amalgamating the capability to take part in high intensity warfare with the ability to fight in COIN campaigns.

So, is the Army beginning to look at multi-role formations again? I know that when it deploys nowadays, the battlegroup , rather than the brigade, is the more likely formation but such groups could come from inside the brigades and have the advantage of common ethos, training etc., which would provide the cohesion, discipline and combat capability you mention.

LikeLike

I intend to address this topic in a subsequent blog post.

LikeLike

Great article. Quick question, given the available funds is the ambition for a globally deployable Division counterproductive to securing a balanced effective force? Could not a focus on UK / BOT defence with a larger mixed regular/territorial force with a smaller brigade/commando sized expeditionary capability be better? Sure it would be nice to be able deploy at a divisional level, but if the kit / logistics does not match the ambition then couldn’t any conflict against any major force just turn into a rerun of the BEF in WW2?

LikeLike

Some technical issues, sorry for the double post…

LikeLike

Repulse,

Without having a forward base in Germany or wherever, we need a globally deployable division as a first priority. The $1 million question is what does that division need in terms of equipment to be sufficiently mobile, but also sufficiently potent. I don’t believe we have really figured that out yet. Quite a few people have suggested that tanks are redundant. They’re not invulnerable and the more heavily protected they are, the more difficult they are to deploy. I’m not sure I’m ready to retire MBTs yet, but it seems pretty clear to me that they need to evolve. A mixed brigade format could work, but again it depends on how it is configured. We also need to bear in mind that light forces might be able to deploy within Europe under their own steam, but a full division with tracked AFVs would need to go by sea. In fact, in most situations, deploying long distance will need to be loaded on a fleet of heavy vessels. Given a wide range of potential threats and the need for a general purpose army capable of performing a variety of missions, I’d like to see two deployable divisions: one a traditional heavy armour division with MBTs and tracked IFVs. And a medium weight wheeled division. Both would be supported by a Royal Marines amphibious Brigade and an SF Brigade. I believe this structure is affordable within present headcount limits. The role of any territorial or army reserve is to facilitate the rapid expansion of the Army in time of war. In the short term, with such pressure on the budget, we may be better off prioritising the Medium Weight wheeled division.

LikeLike

I’m sorry, but what is the real value of a “a globally deployable division as a first priority” when the budget does not support it. Even if we were going to deploy to Europe to defend against a Russian attack what impact would it actually have in addition to the combined US, Polish, German and French forces? Wouldn’t it better to focus our funds (beyond UK / BOT defence) on things that would make a difference? I’m thinking focusing on amphibious and air deployable brigade level capabilities with a global reach.

LikeLike

The point is the budget absolutely needs to support a globally deployable division. Such a force isn’t an extravagance; it’s a common standard across NATO. Divisions are the common currency of modern land warfare. If we don’t have a coherent force that is properly equipped, then we are not equipped to defend ourselves.

LikeLike

If the Warror upgrade is having issues why don’t they rejig the contract remove the gun, use the Warror to replace the FV432, rebalanced the Ajax contract for 350 gun versions by lowering the number of Ares and the PMRS versions. then have them take up the IFV role. You’d then buy wheeled scout vehicles which would later form the basis of the strike brigades. After this has been done and the force been rationalized you’d drip buy the wheeled AFVs you wanted, in a way that would keep the fighting force a little more up to date and relevant, with out costing more (hopefully).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Because Ajax isn’t an IFV and can’t be substituted as such?

LikeLike

Its a heavy IFV (weight only) with extra reconnaissance elements. There’s no reason why with its open architecture that the reconnaissance elements couldn’t be taken out, it already has a seating area, which could be expanded. ASCOD from which its based (much smaller) has 8 passengers. Not forgetting that the Warrior has 7 passengers which i believe is set to go down to 6 passengers. Thus allowing more flexibility regarding dismount composition.

LikeLike

It’s a recce vehicle based loosely on an IFV chassis. It isn’t an IFV.

Even if you took all the recce kit out, it would take substantial modification to change it into an IFV, possibly even re-working the hull. The troop carrier version (Ares) carries something like 6 people total, so how you’d fit 8 dismounts in on top of three crew is a little beyond me.

I suspect you could design an IFV based on the Ajax chassis, but it wouldn’t be as simple and cost or risk-free as some people seem to think it is. You certainly couldn’t take an Ajax, take some racks out and fit some seats and have an IFV. Look at the rear view on the Wiki page.

LikeLike

GD has already developed an IFV version of Ajax. It has an extended crew compartment and an extra set of road wheels. It will easily seat 8 dismounts. It has been developed for the Australian Land400 Phase 3 Competition. It should be excellent and given earlier development work already paid for by U.K. Ajax programme, it will be a relatively risk free option.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But not cost free.

Also, any pictures of the IFV derivative? First I’ve heard of it.

It does kind of make my point that you have to radically change the vehicle to get an IFV out of it. It’s not as simple as switching out a few boxes of electronics.

LikeLike

You’ll see pictures of from March 2018. It should be less expensive than Ajax CRV anyway because it has simpler turret and FCS.

LikeLike

Not possibly a critical deficiency but what is Army’s ability to hinder enemy movement both on tactical and operational level? What are the tools and means to do so?

LikeLike

UK Land Power

‘The US Army fulfilled its rapid reaction mobility requirement via the Stryker Brigade concept. This led to the adoption of the an 8×8 family of vehicles from 2002. Since then, Canada,’

Is this true? I was under the impression that the ASLAV and Canadian LAV were both in service prior to 2000, I believe it was the Canadians who were the first to bite the bullet and use an 8×8 as it’s main infantry carrier pre US Stryker brigades and were planning to go all wheeled by replacing the Leapord 1’s with a wheeled 105mm.

‘The key to attracting high quality recruits is obviously pay and conditions, but also positioning the Army as a door-opener to other career opportunities after a soldier’s military service is complete. Education that helps soldiers of all ranks develop their potential and to achieve high technical standards in performance of their military tasks can only benefit the Army, especially as weapons become more sophisticated and complex. Educational attainment must be backed-up with valid qualifications that employers outside the army will value. Eduction is also important for retention.’

This has been way, way too slow for the army to realise and has lead to a period of time in the 90’s to possibly 2010 of the army offering pretty much qualifications with limited civilian cross over and when they do no record of professional experience to back it up, which in turn has lead to the civilian sector not valuing army service as much as it should (a recent CH4 news segment stated that ex military are offered less pay and less skilled work in general).

The constant positioning itself as the recruiter of the ‘school monge’ or ‘disruptive pupil’ does not help recruit more ambitious individuals who want a challenge, why would you join an organisation that will accept anyone? I think nearly everyone has the memory of a teacher who has stated that a disruptive pupil ‘should join the army to sort them out’.

This is just one point that can turn into a huge debate on the army’s lack of truly identifying and dealing with it’s retention and recruiting issues.

LikeLike

Canada did indeed acquire LAVs some time before the US Army, but USMC adopted LAV25 at the same time. Both USMC and US Army used their 8x8s in combat before Canada. Also, Canada saw 8x8s as cheaper tracked APCs/ IFVs, not as a complimentary Medium Weight capability.

LikeLike

Canada complimented their forces with wheels in the same way as the French decades before they turned to the 8×8. They were using a version of the Pirahna 1 for peacekeeping etc from the 70’s and the LAV III was just an evolution to that concept, they were still used alongside tracks and when vehicles based on the LAV III were adopted in the late 90’s they were used on operations pre 2000, the Balkans being one.

In my opinion I would credit the Canadians for being the first western army to embrace the 8×8 as a frontline apc especially as an IFV regardless of wether cost was the driving factor, which after all is part of the reason that everyone adopts wheels over tracks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The following comment was, I believe, salient to the whole discussion.

“The reality is that when you cut away successive layers of capability, you cannot blame the Army when it is no longer able to perform the tasks you want it to execute.”

My fear is that the; ‘old guard,’ still wish us to have the capability to intervene, almost at will, in perceived world trouble spots. That thinking simply leads us to the situation we are currently experiencing. We gave up the role of the world’s police many years ago and should honestly recognise that fact. As a nation we have huge internal problems that require funding….not to mention the NHS. I often feel that those pushing for greater defence spending have private healthcare and see the NHS as a peripheral need. Whilst on this topic, it might be worth considering, in hindsight, that our greatest achievement in the Afghanistan theatre was the Camp Bastion medical facility. Militarily it would be difficult to see that we achieved any objectives.

The Army has been top-heavy for too many years and somewhat dysfunctional. I appreciate that the top-heavy aspect is now being addressed….but, the problem should never have arisen in the first place. The dysfunctional aspect is, probably, related to the old boy network that is still overriding and probably has more in common with the Victorian era than the current century. Unfortunately, the old boy network does not promote a creative or lateral thinking ethic and consequently there is atrophy. I would not expect James Wolfe (of Quebec), to have made progress in the current Army.

From a strategic and requirements viewpoint, I would severely limit the Army expeditionary capability. Our need is to protect the UK, including the North Atlantic. The focus of that should be the RAF and the Navy. We have, in reality; few real friends in Europe, other than Scandinavia and our commitments should honestly reflect that.

Anything expeditionary, beyond our immediate North Atlantic sphere of interest should entail the use of an expanded Royal Marine force, in conjunction with an updated Para Air-mobile arm.

If we can’t move quickly and effectively, we should seriously question any expeditionary role.

The idea of having a future base in Central Europe is risible and reflects the thinking of a bygone era.

LikeLike

I thought that I would send this to the Critical UK Land Power Issues thread, as it seems like the most suitable.

I am sorry if this sounds a geekish question, as I am dealing with one piece of kit only and only twenty vehicles are in service but it does sound to me as if the MOD is to attempt to flog off even more equipment. I feel that this is the way in which the strength of the British Army is being gradually and seriously eroded (death by a thousand cuts, to use the old cliché). I don’t know whether you are intending to visit DVD 2018 personally but if you go their website (called “The Event”), you will see the heading “Defence Equipment Sales authority (DESA)”. Under it about eight types of vehicle are listed as being available for sale.

Now I can understand that some vehicles which are older in the tooth might be put up for sale: e.g. CVR(T)s, Land Rovers and Pinzgauers. The announcement has also been made that Panther was going. However, what on earth the Buffalo is doing in the list is beyond me. You might very well be interested in what is happening. Buffalo was procured at considerable cost as a UOR and is still a state-of-the-art anti-mine/IED vehicle, a vital part of the Talisman suite. Now, unless the Royal Engineers are getting something like PEROCC from Pearson Engineerng, surely something as expensive and valuable as Buffalo should be retained? This is the way in which the capabilities of the British Army are being stealthily and dangerously reduced. It surely would not cost very much to store them against the next contingency involving COIN.

There is also, unless I have got this wrong, very little on the DVD 2018 website about new kit coming into service. I would be grateful for any of your comments. Or am I worrying about nothing?

LikeLike

This is just me writing up my thoughts and ideas for the dire state of our Armed Forces. It might look a bit amateur, but This is my first attempt to put “pen to paper”

I served as Royal Marine for 9 years, rose up to the high rank of Corporal. I am not a military expert, but a really concerned ex bootneck, on the state of our Armed Forces. I am not a war monger, I believe in Peace through superior firepower. I never wish to see again, young men and women go into combat, I never want to see body bags again, full or hideously disfigured Personnel been thrown on the scrapyard.

If the claims by Military experts and The Defence Select Committee are correct. The Government has to take drastic and urgent action to bring the Armed Forces up to the correct size and equip all 3 Services with the necessary equipment.

Drastic times call for drastic measures and the Government has to no choice but to carry out the required action. Defence of the Realm is paramount, regardless off, in a recession or a buoyant economy.

It is my opinion that the government should divert £5B from the DFID immediately to the Defence budget. It has been suggested by Penny Mordaunt Secretary of State for DFID that funds should be diverted to the Armed Forces while they carry out International Aid duties. We hear some horror stories of Aid revenue being abused and wasted with projects and Spending the budget just to use the whole budget.

International Aid is important for the UK, but do we really have to contribute 0.7% GNP annually on International Aid.? Is International Aid more important than the defence of this country and Foreign policy. Yes, International Aid is part and parcel of this Government Foreign Policy, but you also need a capable Armed Forces to back up the Foreign Policy.

UK spending on foreign aid

For every hundred pounds that’s made in the UK, seventy pence goes towards foreign aid.

Another way to say this is that the government has a target to spend 0.7% of the UK’s Gross National Income on overseas development aid each year. Gross National Income (GNI) is the UK’s annual output of goods and services, plus any income we get from abroad.

In 2016, the UK spent £13.4 billion on overseas aid, in line with the 0.7% target.

Because the UK economy is set to get bigger over the next few years the real value of development aid spending is expected to increase.