By Anthony G Williams

A guest post by Anthony Williams who is a writer on military small arms, automatic cannon and related subjects. Tony has been the Editor of IHS Jane’s Weapons: Ammunition for 13 years and has an encyclopedic knowledge of this field. He has written and co-authored several books on military guns and ammunition, given presentations to many conferences in the UK and USA, and maintains a website at http://quarryhs.co.uk . It is a pleasure that he has agreed to submit a blog post, on such a highly topical subject.

Contents

01 – Introduction

02 – A Breakdown of current loads

02 – Reducing the Collective Load

04 – Providing Individual Mechanical Assistance (Unpowered)

05 – Providing Individual Mechanical Assistance (Powered)

06 – Providing Group Mechanical Assistance (Powered)

07 – Providing Group Animal Assistance

08 – Conclusion

01 – Introduction

One of the most intractable long-term problems facing infantry is the excessive weight of the loads they need to carry. While vehicular transport of some sort will often be available, foot patrols are still a fundamental element of the infantryman’s role and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. That means wearing or carrying sufficient resources to provide protection (including high-grade body armour), weapons and ammunition, food and water, plus an increasing quantity of electronic sensor and communications equipment together with their associated power supplies.

02 – A Breakdown of current loads

A detailed breakdown of the current infantryman’s load was put on display by the British Army at DSEi 2017, with weights for every element. The full list was collated by Nicholas Drummond and can be found here: http://quarryhs.co.uk/BritishArmyEquipmentWeights.pdf

To summarise, the total load weighs 63.9 kg, divided as follows:

Assault Order, including VIRTUS system with 4.99 kg body armour, CBRN kit (4.71 kg), rifle and 4 magazines: 31.5 kg

Patrol Order, including more clothing, belted MG ammunition, etc: 16.26 kg

Marching Order, including more rations, sleeping bag, shelter etc: 16.17 kg.

Since the average weight of a soldier is around 70 kg, that means that he (or she) will be carrying very nearly their own weight when in Marching Order, and still nearly 48 kg in Patrol Order.

Furthermore, the total of 63.9 kg doesn’t include: spare batteries for radios; 40mm grenades; and additional ammunition (in Afghanistan, troops carried 7 or 8 magazines of 5.56mm, plus 200 rounds of 7.62mm link – considerably more than assumed in these calculations).

The consequences of such burdens are serious. From the immediate, tactical viewpoint the problem is the very limited mobility of such burdened troops, especially in rough terrain, and in high temperatures, and at high altitude. In such circumstances there is little chance of the troops managing to close with lightly-loaded irregular forces, and they will rapidly become exhausted if they try.

The longer-term issue is that of the effect on health. Any internet search for “soldier load injury or damage” will bring up a host of reports from around the world (this is a general problem, not peculiar to the British Army). Many of them are detailed medical studies, but in the past this has even reached the popular press: an extract from a Daily Express article of July 2010: https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/188986/British-soldiers-suffer-injuries-from-too-heavy-weights

“The hostile climate and challenging supply chain in Afghanistan means that soldiers must prepare for every eventuality, carrying as much as 5 litres of water and even cans of oil. In addition, the Taliban use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) has seen British troops adopt the unique position of carrying heavy jamming devices, aimed at blocking all mobile signals and preventing the remote-controlled detonation of roadside bombs, in every patrol.

Although the Ministry of Defence does not collate figures regarding skeletal and ankle injuries, Unites States forces have seen a marked increase in “load bearing” injuries. According to the US Armed Forces Health Surveillance Monthly Report, published in April, 7,516 soldiers visited field hospitals for injuries associated with skeletal injuries in 2009 alone. Most of these were categorised as “intervertebral disc disorders”.

“You can’t hump a rucksack at 8,000 feet for 15 months and not have an effect,” said Gen Peter Chiarelli, the US Army’s vice chief of staff. Danish Army figures reveal that 15 per cent of its 750-strong contingent in Afghanistan returned home with long-term injuries. Half of those were caused by heavy equipment, made worse by the addiction to painkillers needed to cope with the load.

Patrick Mercer MP, a former colonel with the Sherwood Forresters who was forced recently to undergo back surgery, ten years after leaving the army, said: “The heavy weight of kit carried by British soldiers has always been a cause for lower limb injury, and I speak as a victim myself.”

Can anything be done to reduce the infantryman’s load? There are several potential approaches, some of which are feasible now while others require further advances in technology, particularly in energy storage.

03 – Reducing the Collective Load

One approach is to reduce the weight of the collective load being transported by the dismounted unit, in two ways: carry less kit, and/or reduce the weight of the individual items. The problem with the first of these is that the kit to be worn and borne has been gone over many times with a fine-toothed comb and the Army is reluctant to omit anything else. The only circumstances in which carrying less might be acceptable would be if rapid resupply were guaranteed, possibly by a drone like the IAI Air Hopper which can carry 100-180 kg and fly for two hours at up to 120 kph. However, armies are as subject to Murphy’s Law as anyone else, so relying on this to work all of the time is unlikely to do much for soldier morale.

Reducing the weight of each item is an approach which has already brought reductions since the Daily Express article was written – e.g. the VIRTUS system and EMAG polymer rifle magazines – and some of the electronic equipment can be expected to become lighter and use less power; batteries themselves are becoming more efficient as well.

The US Army is exploring reductions in ammunition weight by making the cartridge cases of polymer or polymer/metal hybrid materials; this can save from about 20% of the ammunition weight for polymer/brass cases to 33% if all-polymer as in the Cased-Telescoped system also being tested (and up to 40% in MG ammunition by using polymer belt links as well).

This apart, scope for further reductions in weight seem marginal, and indeed more weight might need to be added back: western armies are realising that high-grade body armour is becoming cheap and available enough for anyone to acquire, so are beginning to consider how to defeat it. This might require more powerful (and therefore heavier) weapons and ammunition which may then generate a demand for even more effective body armour, which is also likely to be heavier.

04 – Providing the Individual with Mechanical Assistance (Unpowered)

There are two simple, low-tech approaches to the load-bearing problem which are worth a fresh look with an open mind: carts or trailers, and bicycles (don’t laugh yet – read on!).

The man-pulled cart has a long history and was a standard item of equipment in many armies in World War 2, as shown below (German Army):

And in the following two photos from this site, showing US Army use: http://www.theliberator.be/handcart.htm

These carts are probably too heavy and cumbersome to meet modern requirements. However, something a lot lighter and handier which could prove useful is available off the shelf – the hiking trailer. Some of these have only one wheel as shown here:

Others have two wheels, in some cases with separate shoulder straps so they can be carried as rucksacks when required:

These trailers weigh around 6-9 kg and typically carry up to 40 kg. At least some of them feature quick-release catches so they can be dropped instantly if required.

A 1974 study comparing the energy use of carts with backpacks* showed that on smooth roads pulling a 100 kg cart used up about the same energy as carrying a 20 kg pack. As the terrain becomes rougher so the energy use equalises, but even then trailers reduce the load carried by the soldier, as transmitted via a hip belt, by at least 50%, the rest being carried by the wheel(s). Such a device could therefore provide substantial benefits to mobility while reducing the risk of medical problems.

*(See Journal of applied physiology 36(5):545-8 ·June 1974 )

This is a link to a video showing one of these – a Monowalker – being used in rough terrain including significant vertical obstacles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id5UTB2DHeQ

The humble bicycle also has a long military history. It has often been seen as a way of increasing the deployment speed of the infantry, since on a reasonably smooth path it can travel at several times the speed of a walking man without requiring any more energy. However, it can alternatively be used as a load-carrier, as demonstrated in the Vietnam War (see below). If it is not being ridden it can take a huge load, several times as much as a man can carry, and the wheels take 100% of the weight.

The effort involved in cycling or pushing a bike along a smooth and fairly level track is relatively small, and only on the steepest and most rugged terrain is it likely to become a handicap compared with a backpack. Furthermore, even hard pedaling seems unlikely to cause the kind of impact injury seen from marching with heavy loads. Bikes are normally rather awkward to push as the user has to lean into them at an angle, but notice the extension poles on the bike shown above, which enable the man to walk alongside it.

A rugged mountain bike carrying the Patrol and Marching Order equipment as saddle bags, while the soldier carries the Assault Order load and rides the bike, could benefit mobility considerably – in terms of energy use, reduced physical stress and also in speed of movement. Furthermore, they can still be ridden on rough tracks, although maybe evolutions of the kind shown below would be beyond the capabilities of the average soldier! Such bikes typically weigh 12-15 kg and are built for rough treatment.

05 – Providing the Individual with Mechanical Assistance (Powered)

Adding power to load-carrying systems will dramatically extend their capabilities but usually at a high price in terms of extra weight, and the need to refill their fuel tanks or recharge their batteries. For the present, nothing beats the energy density of liquid fuel, but internal combustion engines bring mechanical complexity and noise. Battery technology is currently developing with astonishing speed under the dual drivers of smartphone and electric car performance, but recharging points are few and far between. This could be ameliorated for infantry load-carriers by making sure that the army’s trucks, APCs etc are equipped to provide fast-charging.

The simplest form of powered load-carrier is the electric-assisted mountain bike. This isn’t much heavier than an unpowered one, typically 16-24 kg. With the most modern technology, the rider pedals all of the time, but the electric assistance engages automatically when climbing hills so this is no more difficult than pedalling along the flat. Regenerative braking helps to recharge the battery when going downhill. As a result, the effective range of these bikes varies between 30 and 75 miles, depending on battery capacity. Most importantly, when the battery does run flat the bike is still entirely usable – it will just be harder to pedal uphill.

Larger and more powerful motorbikes would be the next step, offering a huge jump in capability at a considerable cost. Dirt bikes like the two-wheel drive Rokon shown below are available off the shelf, and have reportedly seen military use. Logos Technologies in the USA has been awarded a DARPA contract to develop the hybrid petrol/electric SilentHawk 2WD trail bike for military purposes, while in 2017 Kalashnikov announced an all-electric-powered trail bike for military and police use, with a claimed range of 90 miles.

Individual transportation for each soldier avoids the all-eggs-in-one-basket problem of relying on a single vehicle which might break down or be blown up, but perhaps threatens to turn the infantry into the cavalry!

Looking into the future and assuming that batteries (or some other form of silent power, such as fuel cells) continue to develop rapidly, the most interesting possibility is the powered exoskeleton.

Exoskeletons might best be thought of as mechanical legs strapped to the natural legs in order to provide powered assistance. Loads are attached to the exoskeleton rather than the body, so are taken by the mechanical legs. This has the obvious advantage that it does not require any separate load-carrier like a trailer or bike, which makes it the most attractive solution in theory. In practice, the endurance of the power supply is critical, because if this runs out, the exoskeleton not only becomes useless – it makes it very difficult for the user to move.

Even further into the future, the exoskeleton may be extended to include powered arms. Ultimately a powered suit of armour could be the end result, but for the foreseeable future that will remain in science fiction!

06 – Providing Groups with Mechanical Assistance (Powered)

One suggestion for dealing with the load is to take it off the soldiers and carry it on a vehicle to accompany the patrol. The vehicle may be autonomous, able to follow the patrol automatically for most of the time. The vehicle could also provide battery-charging facilities for the soldiers’ equipment, have hot drinks on tap, and even be equipped to act as a mine-clearance vehicle, bulldozer or trench digger to provide rapid protection. Since it would only have to travel at marching speed, it need not have a powerful engine: electric drive would be preferred because of its silence. This is technically feasible, but there is a major drawback – no current vehicle can match the ability of a human to traverse rough terrain.

The 8×8 vehicle shown below can carry a section’s load, but it is obvious that if it is faced with a vertical obstacle little more than half a metre high, something a human can step over, it will be defeated. So it cannot go everywhere the troops can.

This problem might be reduced to some extent by using a tracked vehicle, as shown below, although fording rivers may be a problem. Essentially, it will not be entirely solved by any conventional vehicle.

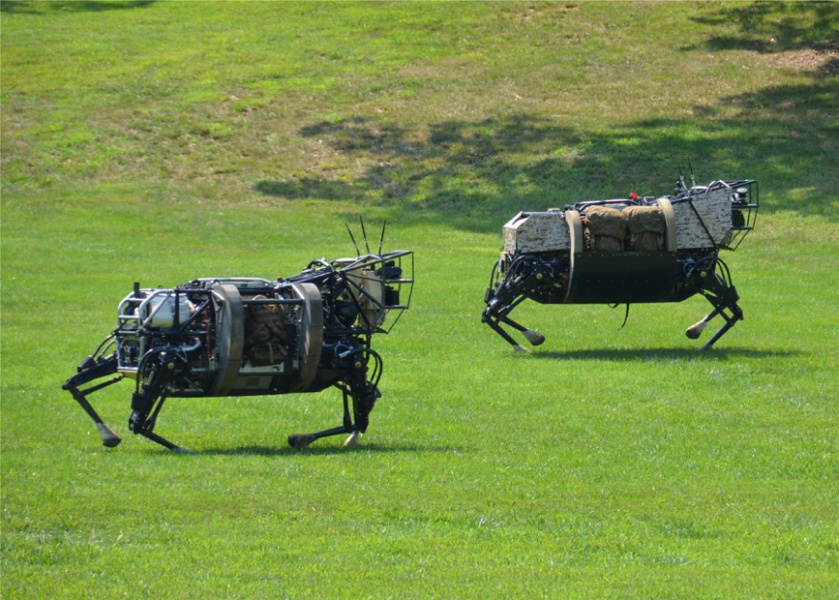

Enter the robotic mule – a four-legged vehicle designed to have a climbing ability comparable with a human, as well as the ability to run. These are at the experimental stage and whether they will be adopted for military service remains to be seen.

07 – Providing Group Animal Assistance

Finally, having discussed robot mules – what about the real variety, which have given good military service in the past (and still do in some circumstances)? I pose this question only because it will inevitably be asked.

Operating beasts of burden is neither cheap nor easy. They require stables, training facilities, feed storage, transportation etc. Soldiers need to be trained in how to look after animals, and specialists like veterinarians need to be available in theatre. Ensuring a steady supply of animals would require a breeding and training program. All of these would be very expensive to establish from scratch, and make operating beasts of burden at least as expensive as motor vehicles, with nothing like the same range of capabilities.

The useful load that beasts of burden can carry will vary greatly depending on the environment, because unless there is plentiful grazing and water available all along the route, large quantities of food and drink would need to be carried for them. They sometimes have minds of their own and refuse to cooperate (as indicated by the phrase “stubborn as a mule”), they make big targets and are bad at diving for cover when under fire. Finally, western societies are increasingly determined in regulating misuse of animals, and the troops understandably tend to get attached to them, so exposing them to the perils of close combat would be unlikely to be acceptable.

08 – Conclusion

There are no completely satisfactory solutions to the problem of the infantryman’s excessive burden. But the penalties of overloading the troops are very clear, both in terms of limiting tactical mobility and in long-term skeletal injury.

While they have some attractive advantages, the problem with all of the “group mechanical assistance” solutions is that they rely on the single vehicle being constantly available which, given the possibility of accident, breakdown or enemy action, will not always be the case. The vehicle also needs to remain in close proximity to its troops, which might not be feasible depending on the terrain. It is therefore desirable for the troops to be responsible for their own kit so it is immediately available to them.

The most promising future individual solutions such as exoskeletons are at a very early stage of development and require further breakthroughs in the density of power storage to provide the endurance needed. Motorists with electric cars already tend to suffer from “range anxiety”; the fear of being stranded if they have no guarantee of recharge facilities en route. This is likely to be a much more serious problem with a military exoskeleton when the user’s life is on the line.

In the meantime, the old but effective technologies of trailers and bicycles are available off-the-shelf. They may not entirely meet military requirements in their present form, but are close enough for evaluation to be worthwhile. It would be an inexpensive exercise to acquire various examples of hiking trailers and mountain bikes (including electric-assisted bikes) and give them to soldiers to use in a wide range of environments to see how their pros and cons compare with that of continuing to carry their present loads on their backs.

*************************

Interesting topic. I’m not holding my breath for robots or exoskeletons helping out any time soon.

Carts, bikes, and ATVs appear to have significant value, but obviously aren’t useful everywhere. It feels like a relatively small investment here could help quite a bit, though.

LikeLike

A truly fascinating article. Intriguing to read about possible solutions such as exoskeletons and hiking trailers. The frightening bit is reading: “western armies are realising that high-grade body armour is becoming cheap and available enough for anyone to acquire, so are beginning to consider how to defeat it. This might require more powerful (and therefore heavier) weapons and ammunition which may then generate a demand for even more effective body armour, which is also likely to be heavier.” So the problem might get much worse.

Incidentally, I understand that the HIPPO-X Light Tactical Mobility Platform, which you show, has been trialled by the British Army and might even enter service. Certainly something is needed to replace the old Supacat ATMP ,which was used by airborne forces and proved so useful, being used not only for re-supply but also for casualty evacuation, re-fuelling, etc. It could carry pallets, ammunition and other bulky stores. It could even mount a weapon for fire support.

LikeLike

Great article – thank you. I think the 80/20 rule comes into play here. While a modern Supacat ATMP or HIPPO-X might not be as versatile and maneuverable over all terrain as a human – what percentage of time will light infantry be operating in terrain that is inaccessible to such vehicles – or a quiet, electric powered autonomous variant ? Not every future fight is going to be the worst Afghanistan type terrain – Korengal valley for example. So I would think these type of vehicles, and the humble 4×4 ATV can have serious utility in many environments, until HALO’s UNSC Mjolnir powered armour becomes available 🙂

LikeLike

The most important thing about getting the infantry’s and scouts’ dismounted loads right is in my opinion self-discipline, not tech.

The more weight technology saves, the more equipment the lads have to carry.

The use of carts will only load to vastly increased loads, not to enhanced agility in proximity to opposing forces.

A change in doctrine that exploits the advantages of superior tactical agility may support a conscious effort by lowering what people think of as bearable loads.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve not mentioned off road segways which can carry loads as well as men trained to use them, scooters can go very fast over small distances on roads and can collapses into a pack. Pack carrying drones and other new tech stuff can be learnt. Platoon strength should have members allready up to speed on these.

LikeLike

Thanks for pointing me to the off-road Segways – I wasn’t aware of them. It would certainly be interesting to put them up against other alternatives in a comparison test. The immediate issues I can see are that it isn’t obvious how the infantryman’s bulky load can be carried on the machine, except on the soldier’s back – so the physical stress caused by such loads remains. And at a weight of 55 kg, they would not be that easy to manhandle over obstacles.

LikeLike

Been thinking a lot about this post. During a recent visit to the US Army’s Manoeuvre Center of Excellence at Fort Benning, I discussed the issue of saving weight with a senior group responsible for equipment procurement. There was unanimous agreement that whatever efforts are made to lighten individual pieces of equipment, any weight saved will soon be “compensated” for by adding something else. So, the idea that combat weights are best controlled by those who lead soldiers in the field is correct. Leaders must ensure that their troops are not overburdened. The problem is that issued load carrying equipment makes it all too easy to exceed sensible limits.

Even before a soldier dons his web equipment, he is wearing almost 19 kg in clothing and body armour. More than anything, it is helmet and body armour that have most added an extra 10 kg in overall weight carried. Body armour has become so good at reducing casualties that it is here to stay.

Looking at the British Army’s new VIRTUS load-carrying equipment, it still defines three basic load levels. Assault order, Patrol Order, and Marching Order. These existed with 1908 Pattern webbing, 37 Pattern, 44 Pattern, 58 Pattern and PLCE 1990. Regardless of the names, each load is designed to ensure dismounted infantry operate with maximum efficiency across mission types and duration.

Assault Order (or Belt kit) is the lightest load level. Infantrymen carry the bare minimum of equipment needed for dismounted close combat.. It typically includes ammunition, water bottle, emergency rations, bayonet, grenades and a respirator. It has always been a struggle to keep the weight of this below 10 kg, but at 12 kg I believe it is already beyond the limit of what should be carried.

Patrol Order (or Fighting order) adds a useful Day Sack that is vastly superior to previous haversacks and kidney pouches. Again, the challenge is not to pack-in too much extra kit. But this adds a further 16 kg of weight and includes more ammunition, rations, cooker, waterproof clothing, an entrenching tool, and miscellaneous equipment.

Marching Order adds a rucksack to carry all of the additional equipment a soldier needs to sustain operations in the field. It includes a sleeping bag, change of clothing, washing / shaving equipment and other miscellaneous items. It adds a further 16 kg of weight.

With these three loads added together, it is very easy to get to 60-70 kg in total weight. This is simply unsustainable.

It is worth noting that UKSF typically carry just Belt order plus Bergen rucksacks . As a reconnaissance platoon commander operating dismounted in Kenya, Cyprus and Belize, we typically adopted this approach. We tried to limit belt order weight to 10 kg and Bergen weight to 25 kg. To do this, we had to ruthless prune whatever we carried.

In many respects VIRTUS is conceptually the same to Belt Order plus Bergen, but usefully adds a Day Sack, to provide additional flexibility when carrying mission-specific kit. While VIRTUS does much to improve ergonomics and comfort; however, the additional capacity / utility it provides only encourages users to add more and more equipment to their combat loads.

Given the long-term health impact carrying excessive weights is having on today’s generation of soldiers, which is the same as heavy loads had on previous generations, the time has come for senior commanders to mandate that soldiers never carry more than 35 kg of equipment, or more than 50% of their body weight, at any time.

LikeLike

An update:

The US Army is exploring the merits of a “group mechanical assistance” solution in the form of a Squad Multipurpose Equipment Transport (SMET). This is to be capable of carrying 1,000 lb (454 kg), to travel more than 60 miles (96.56 km) in 72 hours, and generate 3 kW while stationary and 11 kW on the move. SMET may be optionally manned or unmanned and capabilities could include battery charging, leader-follower control, and other features. Four contenders have just been downselected from an original eight considered in Phase 1:

1. MRZR X – from Polaris, ARA and Neya Systems. This is based on the Polaris MRZR, a conventional 4×4 already in US military service, so has an internal combustion (IC) engine giving a top speed of 96 km/h. It weighs 867 kg and can carry a payload of 680 kg.

2. MUTT (Multi-Utility Tactical Transport) – from General Dynamics. This is an amphibious 4×4 whose wheels can be swapped for a quad track system, it weighs 375 kg and can travel at 13 km/h.

3. Hunter WOLF (Wheeled Offload Logistics Follower) – from HDT Global. A 6×6 using Michelin’s Tweels (airless tyre and wheel unit), this is electrically driven with an on-board generator, weighs 1,100 kg and has a speed of 32 km/h.

4. Howe and Howe have proposed a contender which is believed to be the RS2-H1, a tracked, electric drive, diesel hybrid system weighing 744 kg.

There is as yet no budget for SMET Phase 2, although a bid for funds for a year-long evaluation of these contenders has been made for 2018. The Army is clearly uncertain about whether such vehicles might provide an answer to the problem of the infantryman’s load: the officer concerned said at the beginning of this project: “We’re still struggling to understand this device and what we want it to do for us”. The wide variety of capabilities of the vehicles underlines this.

I can see that this might form part of a long-term solution, in conjunction with an exoskeleton system. The ability of the SMET to provide recharging facilities could combine well with the need to keep the exoskeleton’s power supply topped up at frequent intervals, but the vehicle would not need to be close at hand all of the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

@ Tony Williams

Very interesting to read about the USA’s efforts to provide answers to to the load-bearing problem by using mechanical assistance. Do you happen to know what the latest situation is with regard to British efforts to do something similar? Is the Hippo” vehicle, for instance, (which I mentioned in an earlier comment) a strong contender to enter service?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry, I’ve not read anything about British Army plans for such vehicles. Given the budget crisis for the services, it seems that only the most high-priority programmes stand much chance of progressing.

LikeLike

“It is worth noting that UKSF typically carry just Belt order plus Bergen rucksacks . As a reconnaissance platoon commander operating dismounted in Kenya, Cyprus and Belize, we typically adopted this approach. We tried to limit belt order weight to 10 kg and Bergen weight to 25 kg. To do this, we had to ruthless prune whatever we carried.”

Packing by strictly regulated list is one method that works fine for recon troops since their mission isn’t to engage the enemy head on. They can focus on mission (radios&optics mainly) and survival items.

Infantry has to have some sort vehicles even if they’re just civilian pick ups. Infantry platoon moving into contact needs so much ammunition and anti tank weapons that it’s overburdened if it needs to carry all of it. It needs to have reserve, not only in tactical sense but also material wise.

Is the need for these burden carriers coming from cracked backs and broken pelvises caused by patrolling in Iraq or moving overburdened into contact back in States training for conventional war. US army has had 80 years since motorization started in larger scale to motorize infantry and still were talking about this. Am I the only one to who this doesn’t seem to add up? Has “dismounted infantry ethos” gone too far?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always been impressed by the VC carrier bike concept,but I hadn’t noticed how well engineered the extension handle was(complete with brakes as well)

I bet 100 of these would have been welcome when trudging acrross the Falklands. Obviously they would be extremely useful for transporting troops as well and the batteries would be useful for an infinite number of things,including thawing out frozen troops and smokless tea making.Without a battery its still very useful and is cheap enough to abandon if nessicary.

Keep BAE out of it,buy in bulk cutting out the retailers cut,and I think that about £2000 gets a pretty good and stromg e MTB .Manufacturers would fight hard for the prestige of this order.Another £1000 for racks and modifications and £1000 a year for maintainence,troops (no need to wear them out with training as any soldier can already ride a bike).Clearly not suitable for a lot of operations,a couple of hundred would be enough to be going on with.

This is not enough meat for the military/industrial complex,so we’ll just let our enemies carry on with this effective technique,while we spend a billion on ridiculess robotic mules.

A wheelbarrow is extremely cheap and surprisingly effective,particularly when used as a lever for lifting heavy items

LikeLike

One solution to this challenge was the US M274 Mechanical Mule of the 1960s. Going back to 1940 and you have the Jeep. In the 1970s I saw Bundeswehr motorcycle troops on the march with what looked like dirt bikes.

LikeLike

This reminds me that around the 1970s I think that the British Army had something (for trial if not in service) very similar to the M274 (maybe even the same), probably for paratroopers, which they called “the Bug”.

The reason I remember this is that it featured in a semi-serious TV motoring programme involving a race, I think between military off-road vehicles, around a 4×4 test track. At the climax, the rather excited commentator announced “…and the little Bug has come in last!” (to get the unintended joke, you have to say it out loud, quickly!).

I have been unable to find any reference to it on-line, however.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On the subject of mountain bikes, I recently found this, available to buy, off the shelf: https://www.montaguebikes.com/product/paratrooper/

That thick central frame seems an obvious location for a battery if electrical assistance is required.

LikeLike

Is it time to reconsider the concept of Light Infantry?

LikeLike

You took words out of my mouth. We can have infantry without any vehicles or anything but then their mission can’t be fighting, atleast not head on. Guerrilla tactics need to applied to light infantry without vehicles and their ability to sustain operations. Should we start to think of motorized infantry that fights dismounted as light infantry? Is the “light” referring to firepower or the space and weight required to move infantry with its equipment?

Is all infantry without armoured vehicles light infantry?

My opinion is that all infantry except those that mean to fight dispersed using guerrilla tactics should be motorized, period. Light infantry that fights as a unit is very suspectible to indirect fire unless dug in. Roles and equipment should be as follows:

– Light no vehicles, dispersed, guerrilla tactics

– Light non-armoured vehicles, defensive operations

– Medium armoured vehicles (6×6, 8×8, MTLB, BV410 and such), defensive and limited offensive operations

– Heavy armoured vehicles, offensive operations.

No matter how much we try to lighten the load we still need much more ammunition, mines, equipment, AT rockets and missiles than we can carry. Only answer is full motorization.

LikeLike

I wholeheartedly agree. How about using refurbed MRAPs, bought during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to outfit light infantry?

http://interestedamateur.blogspot.com/2016/12/pimp-my-ibct.html

LikeLike

That’s better than no vehicles. TO&E about USA BCTs states that IBCT rifle company has two or three vehicles if I remember right. Basically it has no vehicles and such formation is next to useless in my opinion. Battalion support company has moblity section of ~10 trucks to move the three rifle companies.

LikeLike

A very interesting analysis of the US SMET programme is here: https://ndiastorage.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/ndia/2016/GRCCE/Massey.pdf

LikeLike

I’d like to add that Sparky (widely considered an obsessive troll) has written a lot about the ‘carts and bikes for infantry’ theme on his combatreform website. I still consider that stuff as niche tools, just like using mules, llamas and KraKas. BTW, mentioning the Kraka of the German paras:

The Americans had something similar, less ambitious in the Vietnam era (they called it “mule”, forgot the designation). Essentially, these things are predecessors of multi-seat ATVs.

You cannot take them with you everywhere. No climbing, hardly any trench crossing, little ability to use microterrain for convealed movement.

—————————-

“– Light non-armoured vehicles, defensive operations”

Positional defences are extremely questionable. Defence should rather be about observation, ambushing, delaying tactics. The latter two require high mobility – indeed higher mobility than the advancing opposing forces use.

Steel is cheap. APCs based on 4×4 or 6×6 trucks with nothing added but simple RHA plates should be afforded. You need to ward against people getting overambitious and aiming at STANAG protection levels, though.

LikeLike

Should just adding steel plates on trucks be as easy we would have seen such thing already. Defencive operations against enemy with potent artillery and ISR capabilities require illusiveness, dispersion and mobility like you said. I have not at any point said we should just dig down and wait for untimely death by artillery. Delaying tactics and ambushing doesn’t need mobility if the troops are meant to stay behind enemy lines. If they mean to trade space for time then mobility is needed.

I believe it was Chechenyan war where they had fortified one area properly and that area sufferd least casualties. Fortifying has place in modern warfare. Having several positions all over the AOO enables fighting from hardened positions and moving into next fortified position.

LikeLike

We have seen it.

https://www.google.com/search?q=hillbilly+armor&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS762US763&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiSuunojcfYAhVFGt8KHaWwBoUQ_AUICigB&biw=1263&bih=887

LikeLike

Don’t mean to nitpick but sure we could call Humvee a truck. I had something that can carry an entire squad and their gear in mind when talking about trucks. Maybe it’s a about how the word “truck” is translated into different languages.

Do we examples of hilly billy armor for these sort of trucks?

LikeLike

Yes,

But then the US made a concerted effort to build in armor at the factory.

LikeLike

These examples are much bigger, heavier and expensive than needed to fill the role suggested by the topic of reducing the infantry’s load. It is like shooting squirrels with an elephant rifle.

LikeLike

My point was that you need self-discipline to come up with a proper APC that can be afforded for a large-enough (mobilised) infantry force (and I don’t care about peacetime strengths – I care about whatt can be deployed where it matters within few days and then what can be deployed within a month).

If you don’t use self-discipline and self-restraint you end up with monsters such as Boxer; more expensive per passenger seat than a business jet.

A self-restrained affordblke APC would look more as the French Bastion (based on VLRA 2nd generation, not quite satisfactory due to 4×4 @ 12 tons – the VLRA 6×6 would have been more promising):

http://www.military-today.com/apc/acmat_bastion.htm

related

http://defense-and-freedom.blogspot.de/2014/11/newest-plans-for-more-gtkmravboxer.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, SO. Simply adding truck-based, armored, organic vehicles to light infantry will not only vastly improve mobility over many terrain types (especially roads), but should also gives them a place to stow their Patrol/March Order kit.

Yes, these vehicles can’t go everywhere. There will still be instances where troops have to hump it significant distances with heavy loads, but are these really the norm? Or are they the exception?

The US Army plans to keep and reset 5,600 M-ATVs. IMHO, as part of the reset, we should extend the wheelbase of some and convert them into M-ATV Assault APC (and other) variants.

The rear six seats aren’t blast seats, so it’s not perfect. But I bet it’s much more economical to modify existing, in service vehicles than design and build brand-new ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m no fan of blast seats. Roof-suspended folding benches would be MUCH better.

That way an APC could easily be used for CASEVAC (litters) and munition resupply (pushiung in and pulling out pallets).

Underbelly blast mine explosions that are powerful enough to do much harm without belly penetration were almost unknown in any setting but wars of occupation and Israeli Gaza raids. They’re to be ignored when your intent is deterrence and defence.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise to you, but ofc I’m not convincing all the time:

http://defense-and-freedom.blogspot.de/2016/10/medevac-and-casevac.html

LikeLike

I have a feeling the lack of blast seats is just a symptom of a bigger issue. Often these MRAP-type vehicles consider the rear payload area to be “sacrificial”, and don’t have the same blast protection as the rest of the vehicle.

They focus protection on the crew capsule.

If true, even blast seats or folding roof-suspended benches may not be of much use.

I’m still ok with that for the purpose of mechanizing light infantry. It’s still better than the Mk 1 Leather Personnel Carriers they have now.

LikeLike

The US Army’s plans are progressing (note that by “mule” they do not mean a vehicle with four legs!): http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2018/2/9/army-on-accelerated-path-to-buy-as-many-as-5700-robotic-mules

LikeLiked by 2 people

The first photo in the leading-in article is about a soldier heading for a COIN mission. Whatabout coming kitted out for a peer-to-peer outing (this guy has already dug in the AT-mines he was issued with): https://alchetron.com/cdn/finnish-army-c4feaf8b-880b-4faf-adb4-648d766d78b-resize-750.jpeg

LikeLike

Exoskeletons and Robots sounds nice, but I would prefer a low-tech approach to this heavy (pun intended) issue. Skip the “better safe than sorry” attitude and reduce the load to the things which are really needed. In addition, give more thoughts to logistics so that the troops can get supplies more reliable. These are the things which can make the difference, until those fancy technology solutions are available.

The German Army has been using mules and horses for 60 years in the mountain troops and is still satisfied. Experiences from Afghanistan showed that the animals are also a valuable support there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed, Franz.

Really, pack animals, mules and such (the actual animals, not mechanical approximations), are the most viable, cost-effective and time-tested option, bar none; but they got what could barely be called a cursory treatment in this essay. Very strange, imo.

Also, much of the negation for pack animals is spurious (eg. ‘soldiers get attached to the animals’: seriously?), or is not applied objectively across other systems, eg. citing fodder, veterinary and other support factors as characteristic for pack animals seemingly rests on an implicit premise that other transport systems do not have “vets” or “wranglers,” or “fodder,” but what then are motor pools, enlisted techs, recovery vehicles, fuel, fuel trucks, fuel depots, security forces for all the aforesaid, etc.? Mules can be stubborn, but other mechanica will always respond to commands? Etc.

In other words, pack animals were evaluated in this essay as part of a system, necessitating support and logistica of its own, whereas other powered systems were looked at for what they can furnish in themselves, in terms of just carrying troop kit, not also in terms of what they *introduce into systems themselves* as mechanica, save for the exoskeleton, albeit the only friction cited for exoskeletons being power loss or broken power transfer, which is still very much unfair to pack animals.

And this is all speaking in terms of friction and costs, not really delving into battle area tactical factors or even operational level tactical considerations (the only ones touched on in the essay being low-obstacle clearance, ‘diving for cover’, and enduration of fires) where pack animals actually have several advantages.

For one, the very real likelihood of EMP weapons in future battle spaces, and the resultant vulnerabilities around everything being plugged in to some digitized machine. For another, the fact that pack animals are, by far, the most dynamic and capable of existent systems in negotiating rough, inclined, soft and hazardous terrain. Still another, potentially decisive advantage of pack animals, is that their “signatures” are incredibly low-observable, whether IR, EM, acoustic or seismic, relative to internal combustion vehicles; and while some of the other options discussed are low key too (bikes and such), this comes full circle to the idea of negotiating terrains and load capacity per the amount of space the vehicle occupies and needs to maneuver, so pack animals are the lowest observable system for the given amount of load transportation potential.

The powered “mules” are potentially the ‘best of all worlds,’ but are also still in R&D phase at this point, which the essay does recognize.

Anyway, I really think that, at the end of the day, the reason people shy from exploring the pack animal concept more is because it looks “too barbaric.” It is too anitquted. Bicycles and carts are ancient too; but men fashion them completely, put their “stamp” on them: they’re human artifacts, not animals/organisms, after all. Pack animals offend against Post-post-Modern sensibilities that men have “arrived” at the future, and they’re something that far below-peer enemies can and have utilized too, which is troubling to many military theoreticians, who would prefer to see qualitiative superiority in terms of tech and domestic economic complexity.

But as Patton said, if it’s stupid but it works, then it isn’t stupid.

LikeLike

I think you have noted some very interesting points, appreciate it for the post.

LikeLike

Frankly, the solution is simple, but the brasses and pencil pushers overlook it.

Solution? Carry less shit. If you don’t need something, ditch it. Forget “packing lists”, let the field soldier pack what they need themselves.

Command can seriously help out by giving out those BP-5 type rations instead. It taste like a bar of questionable butter but at least it’s light, and frankly lightweight is everything in the field.

Teach infantry to operate enemy weapons. If you’re lucky enough to run into left-behind weapons and all you need is make noise and suppress insurgents, conserve your M855A1 or some exotic precision weapon ammo they issue these days. Grab an AKM or a PKM lying around and hose.

Allow foxhole-dwellers to make their own decisions, and they’ll make the decisions that won’t wreck their backs.

LikeLike

Travel light and fast , water, ammo , food and light weight comms ,if you cant travel as fast as your enemy you cant catch them , aerial back up drones for intel and replenishment , too much weight will get the infantryman killed or give him permanent skeletal damage ,

LikeLike

We talk about making stuff lighter or carrying less stuff or getting something else to carry it as our only options but medium range support is also a way of carrying less HE / getting something else to carry it.

Our foot patrols (walking around until someone reveals themselves) are difficult as the enemy are probably the ones choosing the contact location, so we should be heavy on 5.56 and 40mm (HE & Smoke) to break contact quickly and have a 120mm vehicle mortar or similar on call to defeat the target.

LikeLike