By Nicholas Drummond

This is an updated version of an article originally written for the Wavell Room blog in June 2018 (see wavellroom.com). It makes a case for a flatter hierarchy by cutting the number of ranks we have today by a third. This is a controversial topic, but one based on a belief that, if UK Armed Forcers are to reflect the nation they serve, then they must incorporate the ways in which contemporary society has evolved. One of the most important changes we’ve seen in industry and commerce in recent years is a reduced number of corporate rungs. Today, the technically competence of an employee has become just as important as absolute seniority or the management position held.

(Above) British Army Brigadier. (Image: National Army Museum)

The case for change

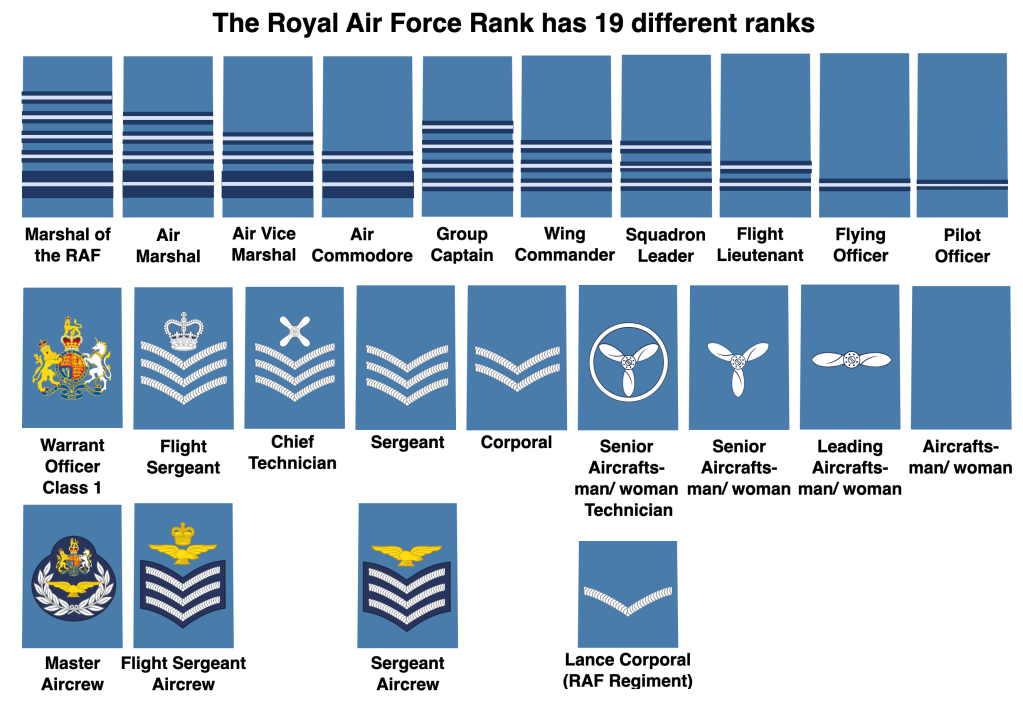

Today, the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force have 16, 18 and 23 different ranks respectively. Compared to other organisations, including commercial and government entities, this is a substantial hierarchy, especially when you factor-in five levels of General rank. Those who defend the existing rank structure argue that the manpower-intensive way in which the Armed Forces operate demands a hierarchy that allows effective command and control at all levels across each service. You need to know who is responsible and to whom responsibility devolves in case a commander is injured, killed or captured. Further, the current rank system has been in use for more than a century with proven utility in two major conflicts as well as countless small wars. This means that even the most compelling case for change will be met by stiff resistance. Given the likely reluctance of senior officers to accept the need for change, the first job of this article is to explain why the system is broken and what the benefits of change would be.

(Above) The NATO Armed Forces Rank System allows for 10 Officer Ranks and 9 Other Ranks. Do we really need such a hierarchical and stratified system?

Five reasons to consider streamlining the total number of ranks across the UK’s armed forces:

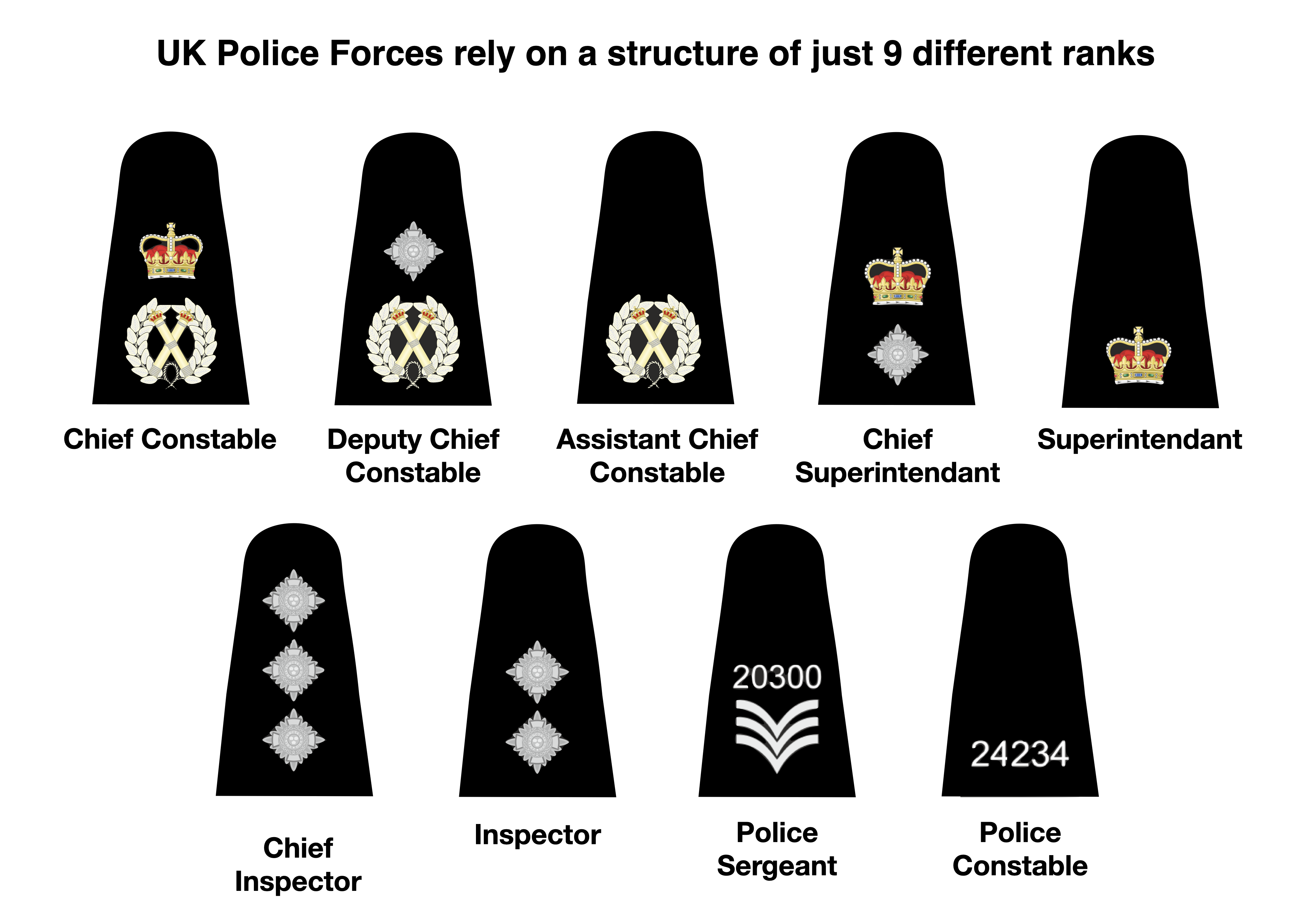

1. The Armed Forces are smaller. The total number of British Police Officers is 123,142[1] yet the Police Force manages to do with a total of just nine different ranks. Contrast this with any major UK professional services firm and you’ll see that they also adopt lean structures. Typically, they have just five management levels: Associate, Associate-Principal, Principal, Director, and Managing Director. Thus, the first reason to consider a rationalisation is the size and structure of Britain’s Armed Forces. The days of a standing army of 300,000 men are long gone. The largest of Britain’s services, the Army, has only 77,000[2] soldiers. Is the command of soldiers, sailors and air crew, even in combat, so demanding that we need such an extensive array of hierarchies? Given that UK Armed Forces have evolved so much over the last century, a flatter structure might actually simplify things and make command easier. Moreover, Warship crews, Battle Group structures and Fighter Squadron compositions have become much leaner. We can expect this trend to continue, especially as we embrace AI and autonomous weapon systems more widely.

The reduction in size of UK Armed Forces was not accompanied by a reduction in the number of senior ranks. After all, why would you want to get rid of a large number of competent senior officers with experience and ability? However, it means that the British Army has become top heavy. Today, the Army has 207 generals (brigadiers and above). This is almost more generals than tanks.[3] Even so, the Army still has one general for every 400 soldiers. Similarly, The Royal Navy has 121 Admirals (Commodores and above) but only 49 active warships.[3]

2. The nature of leadership has evolved. Discipline and obedience to vital direct orders remain paramount, but today’s soldiers, sailors and air crew are more self-disciplined and educated[4] than their predecessors, and therefore more capable of independent thought, judgement and action. It means that military leadership is less dependent on rigid chains of command to get things done. Better educated junior ranks translate directly into more competent junior leadership, which means command can be delegated with confidence. This is important, especially when personnel on the ground are likely to have a more informed view of a tactical situation than senior officers tucked away in HQs many kilometres away from the action. The concept of the “Strategic Corporal,” [5] which is the recognition that junior commanders can directly influence mission success despite their position, by exploiting time-critical information that enables them to take the best possible decision on the spot and at an appropriate moment, stems directly from this devolution of leadership. This means we can and should rely more on junior leaders.

Today’s soldiers no longer need to be bullied into obeying orders, unlike their forbears going over the top during the First World War, who were often described as being more afraid of their own NCOs than they were of the enemy. This is because contemporary service men and women are more motivated and self-disciplined, not least because we have professional forces not conscripted ones. Special Forces unit leaders tend to adopt a more relaxed style of command, because they know that the soldiers under them have a great sense of purpose and the highest standards of self-discipline. But such attitudes are not just true of UKSF; they are hallmarks of all three UK services.

3. Flatter structures tend to promote greater teamwork and mutual dependancy. Another reason to consider fewer ranks is that flatter structures help to promote teamwork and mutual reliance. The quality of NCOs today is superb, and having fewer commissioned officer ranks would make it easier to provide upward feedback. We all know how difficult it is to “speak truth to power” but it is essential, given that lives depend on good leadership decisions. The apocryphal story that illustrates this is the Field Marshal whose staff officers only tell him what they think he wants to hear, rather than what is actually going on. So, he leaves his HQ and visits a forward unit where he finds a platoon sergeant who tells him the unvarnished truth. Less hierarchical structures promote good communication between team members, both upwards and downwards. They foster a group dynamic that promotes cohesion and cooperation. This allows tasks to be completed in a way that focuses on who does what, not who is in charge. In days gone by, a clear chain of command was essential because communication above the noise of battle was so challenging and because casualty rates were often so high. But, even during the First World War private soldiers naturally took command of Sections or even Platoons when the established chain of command broke down.

4. Technical competence to operate different weapon systems has become as important as management of units. Increasingly, today’s forces are reliant on weapon and equipment systems that require a high degree of technical skill to operate them. This means that force structures need to be focused more around professional skills than ranks. A streamlined rank structure would help to disconnect rank with role. It also means appointments could be based more on ability rather than just seniority. Increasingly, we’re seeing how important it is to reward talent with greater responsibility earlier. If we want to retain talent, then we need to recognise not only competence, but equally effort and commitment.

A further benefit of this approach is that it could be used to disconnect pay from years of service and absolute seniority. There might still need to be minimum and maximum pay bands for each rank and such an approach ought to apply to warrant and non-commissioned officers as well as commissioned officers, but it would create a greater incentive to do well, which would help motivation and retention. Thus, you might set pay bands for each rank, but include some kind of annual bonus for meritorious service and ability. It means that a younger and promising junior ranks might be paid the same or more than an older and less motivated senior rank. In any event, if we linked pay more to performance rather than just time in the job, we could start to see other efficiencies, including a reduction in the duplication of roles.

Technical competence is about education. Many soldiers who join the armed forces may be intelligent and capable, but not have benefitted from the same quality of education enjoyed by commissioned ranks. One of the great strengths of all three services is that they facilitate personal and professional development. The ability to unlock potential and create new opportunities post-service has been a longstanding aid to recruitment. With industry and commerce requiring higher standards of technical competence, the Navy, Army and RAF may no longer train service men and women to same standards as commercial firms. If this is correct, then technical training must be re-prioritised.

5. British society has become much more classless. Another reason to consider change is that the existing rank structure reflects what used to be a much more socially stratified UK society, which existed until after the First World War. Today, Britain is a meritocracy and although not quite classless, previous divisions have become irrelevant. Someone’s family origins and connections no longer matter; it is who you are as a person and the qualities you bring that count. It means that where you went to school no longer matters. Former Chief of the Defence Staff, Air Marshal Sir Stuart Peach, attended a State school and reached the pinnacle of the armed forces. Twenty to thirty years ago, a non-private education might have counted against him. This is as it should be. Higher standards of education have done much to promote equality and it is right that UK Armed Forces should reflect contemporary society. This means, as well as having fewer ranks, we also need to remove some of the non-professional barriers that prevent talented non-commissioned officers from obtaining commissions. Further to this, we need to consider the need for lateral entry. Experienced civilians entering or re-entering the military, and used to flat hierarchies, are likely to find current structures cumbersome and unbearably rigid. This could be detrimental to attracting technically skilled people.

An integral part of streamlining the total number of ranks is to reduce the delineation between Officer and Enlisted Ranks. A smaller number of senior ranks will help the Armed Forces to become more classless and less stratified. In particular, it would be helpful to allow Warrant officers to assume command roles earlier in their careers as well as making the transition from Enlisted to Commissioned status easier.

We talk much about transforming the Armed Forces so that they are a truer reflection of society, but UK Government figures on Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority (BAME) integration into UK Armed Forces[6] suggest that more needs to be done. Anyone who can achieve the required standards should qualify for promotion. Creating a flatter, fairer rank structure is a step in the right direction towards giving talented individuals deserved recognition, regardless of gender, sexual orientation and ethnic origin.

Education as a key enabler of a flatter rank structure

As has already been suggested, education is an important part of a flatter hierarchy. So an important enabler is offering professional qualifications to all those who want it, regardless of age, rank or unit. Education is expensive and time consuming, but while training prepares you to manage expected situations, education that enhances your mental faculties:, i.e. that teaches you to think, helps prepare you for the unexpected. When it comes to problem-solving, especially in extreme circumstances, education can be a force multiplier. On a practical level, professional education will help personnel of any rank achieve greater recognition while serving. It also paves the way for a career beyond the services. Positioning the services as a route to a desired career is an effective way of attracting talent. We know that specialised qualifications have become extremely important for industry and technical professions. The challenge is to provide education that gives each service the technical skills it needs while ensuring that specific qualifications have utility beyond military service. A large part of this is promoting a mindset that values education and professional development as a career enabler. We need to look beyond basic degrees too. Allowing personnel to study for advanced degrees, Masters and Doctorates, would do much to promote the Armed Forces as a source of thought leadership.

The opposite is also true. Is it still acceptable for any officer to join the services without a degree and to command personnel who are better qualified than he or she? Or, to put it another way, can leadership be effective without technical training that reinforces the authority of command decisions?

If a reduced rank structure is desirable, what is the optimum number of ranks?

If the case for a flatter rank structure has been established, the next question is: what is the optimum number of levels? To go from 18 to 9 ranks might be too radical a change. But any reduction cannot be an arbitrary decision, but based on the minimum number command levels necessary to ensure effective command, control and communication in battle. At a basic level, we can divide command levels as follows:

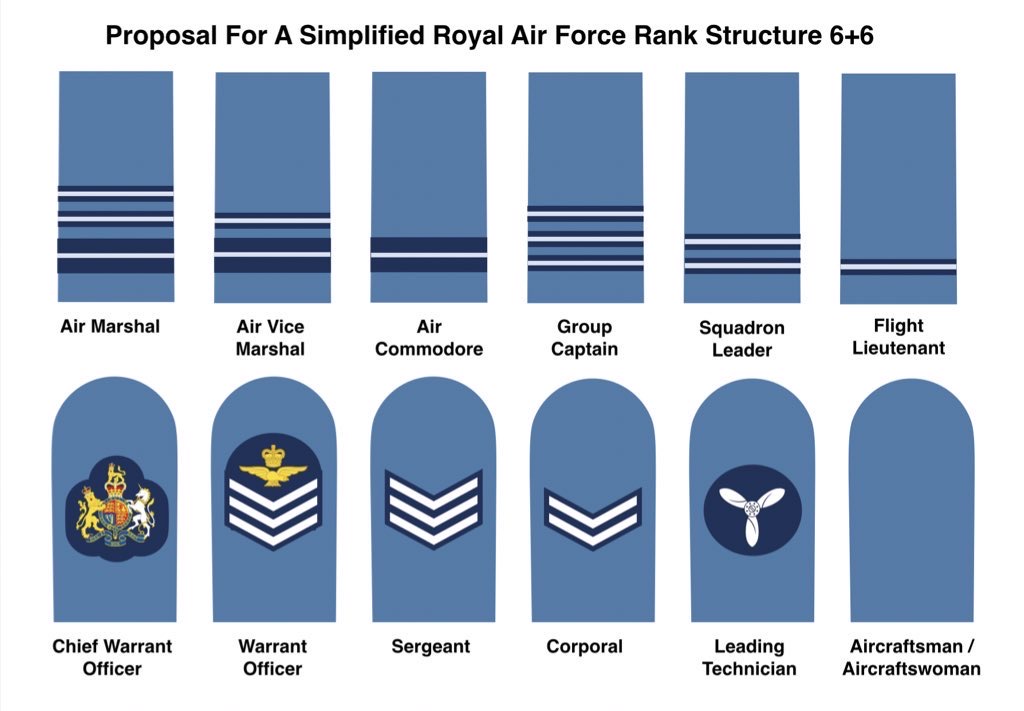

With this in mind, a reduction to just 12 ranks is proposed. This would include six commissioned Officer ranks and six Enlisted ranks. Using the Army as an example, the lowest rank would be Private and the highest General. While there would be an increased number of officers holding the same rank, defining necessary hierarchies for effective command would be achieved by role appointments, e.g. Company Commander, Ship’s Captain or Squadron Commander. The following six commissioned ranks and six non-commissioned ranks are proposed:

(Above) The proposed simplification of the UK armed forces’ rank structure would streamline the total number to 6 Officer Ranks and 6 Enlisted Ranks. The approach would aim to harmonise rank titles and insignia as much as possible, but without sacrificing the heritage and tradition of each service.

Any approach to simplify the total number of UK Armed Forces ranks must be relevant to contemporary needs and forward looking. It must manage the levels of command relevant to all three services. It must maintain tradition and links with the past. The resulting structure should be simple and easy to understand.

For the sake of commonality across the forces and simplification across different Army branches, it is proposed that the anachronistic and confusing practice of having different names and insignia for the same rank is replaced with a common structure across all three forces with only minor variations in name. So three stripes would denote a Sergeant in the Army, as it always has, a Sergeant in the Royal Air Force, but, for the sake of tradition, in the Royal Navy this rank would still be called a Petty Officer and use a system of anchors.

We also need to recognise the increased number of women serving in all three forces. Although it’s acceptable to call enlisted soldiers “Private,” ‘Trooper” “Gunner” and “Sapper,” it is not correct to refer to a female soldier as “Rifleman,” “Kingsman,” or “Guardsman.” This is also true for the Royal Navy with the the rank “Able Seaman,” or the RAF with “Aircraftsman.” Therefore, it is proposed that gender neutral ranks be introduced. All enlisted personnel within the infantry would be called “Private,” while Royal Navy male enlisted personnel would be called “Able Seaman” with the corresponding rank of “Able Seawoman” introduced for female enlisted personnel. However, like the Army, it might be simpler to refer to all naval enlisted personnel as “Sailor” or “Able Rating.” Similarly, Royal Air Force enlisted personnel would be called “Aircraftsman” or “Aircraftswoman,” though it might be worth exploring whether a new and simpler gender-neural rank could be introduced, e.g. “Technician.”

To complement a reduction in ranks, four levels of technical qualification are proposed with service badges that denote the level of competence achieved. For each service, these could include:

- Standard level of military competence

- GCSE equivalents

- Degree equivalent

- Advanced degree equivalent

Part of professional development would obviously include standard military topics such as Weapons, Doctrine & Tactics, C4I, Information Technology, and Logistics, but other subjects like Accounting & Finance, Modern languages, Politics & Diplomacy could also be included. Encouraging all ranks to develop their scientific knowledge would encourage high technical standards across specialist arms, e.g. Law and Mechanical Engineering.

There can be big difference in how officers treat a junior rank who possesses an advanced degree or superior technical competence. When the opinion of technical expert is sought, it can dramatically improve decision-making and thus operational effectiveness.

In terms of implementing a reduced number of ranks, it is important to focus on the concept of a streamlined approach to command levels, not the names of the ranks or insignia used used. So while the examples that follow are illustrative, they are not in any way prescriptive.

(Above) Naval officer ranks would use the two of existing ring-type rank insignia with third thinner ring abandoned. There are two senior admiral ranks, two middle ranks, and two junior ranks. Enlisted ranks remain unchanged with six levels and the existing insignia are also retained using the traditional system of anchors. It might be desirable to add stripes that correspond to the Army and Air Force ranks of Lance Corporal, Corporal, and Sergeant for easier cross-service rank identification.

(Above) Creating a reduced rank structure for the Army is more problematic, because it has traditionally used multiple insignia type. It is proposed that, like the Navy, just two rank insignia are used, the pip and the sword & baton crossed. Like the Navy, this creates two general officer ranks, two middle level ranks, and two junior ranks. A Company or Squadron would be commanded by Captain. A regiment would be commanded by Major or Colonel. A Brigade could be commanded by a Colonel or Vice-General. Enlisted ranks would continue to use traditional stripes, but WO2 and S/Sgt ranks merge into a new Warrant Officer rank.

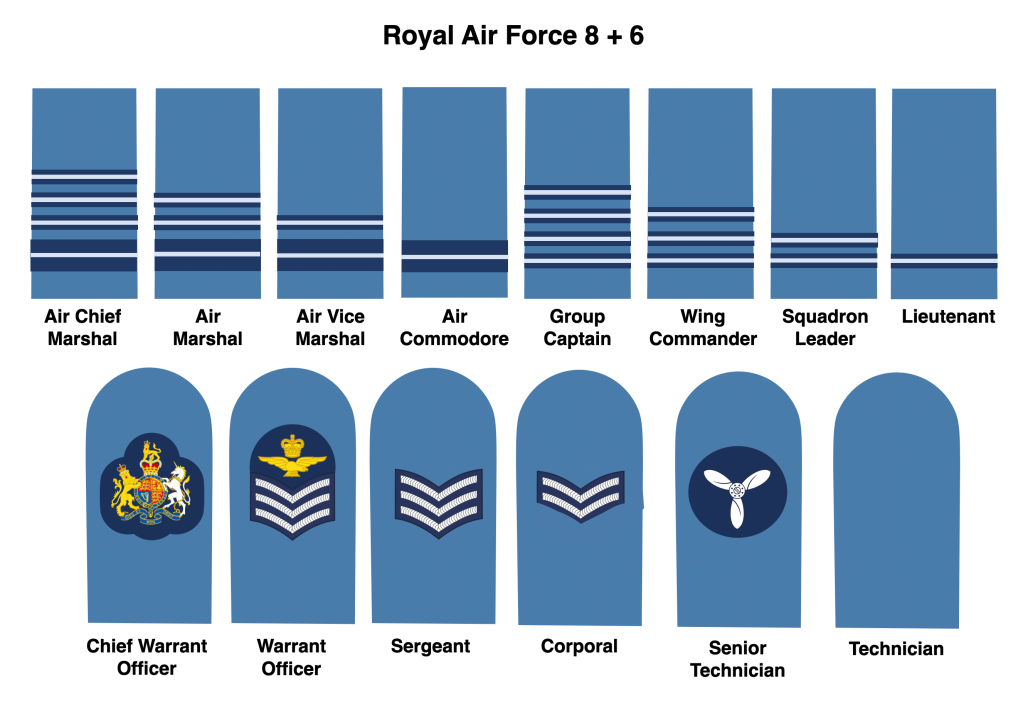

(Above) The Royal Air Force would continue to use the existing ring insignia types, but, like the Navy, the third thinner ring would disappear. The Enlisted Rank structure follows the Army, as before, but merges Flight Sergeant, Chief Technician, and Aircrew ranks into a new single Warrant officer rank.

An OR-1 (Lieutenant) would promoted to OR-2 (Commander/ Captain / Squadron Leader) after 3 to 4 years of service. An OR-2 would be promoted to OR-3 (Captain/ Major/ Group Captain) after 8-10 years of service. An OR-3 would be promoted to OR-4 (Commodore/ Colonel/ Air Commodore) after 15-20 years of service. An OR-4 might be promoted to OR-5 (Vice Admiral/ Vice General or Vice Air Marshal) very soon after making it to OR-4, based on merit, or might not be promoted further at all. Across all three services, OR-5 and OR-6 (Admiral, General, and Air Marshal) would be rare with not more than 40-50 per service.

Pay would be linked more to role than absolute seniority. it would also reflect personal development and the level of professional development reached. For example, an experienced and highly competent Navy Warrant Officer could be paid more than a junior less technically skilled Lieutenant.

It may be too much to reduce all three services from their current number of ranks to just 12 in one go. If this is the case, it might be preferable to move to an interim number of 14 ranks with eight officer ranks and six enlisted ranks.

(Above) An interim approach to rank reduction might streamline the total number from 18 to 14. Enlisted Ranks would be reduced as already described to 6 ranks, while officer ranks would be reduced to 8 instead of 6. In this case, a new rank between Lieutenant and Captain is added, while a third General rank is retained. The Army rank of Lieutenant Captain is designed to correspond with the Naval rank of Lieutenant Commander.

To summarise, any attempt to streamline the total number of ranks would require a revised system across NATO, so that the armed forces of all member states would reflect the same number of command levels. If there was wide scale buy-in to the benefits, then changing structures across NATO would not be that difficult to implement. The only real barrier to change might be the attitude of senior officers who might feel threatened or marginalised by a perceived loss of status. So, this exercise might need to be a political one rather than a military-led initiative.

Whatever the process or the resulting number of ranks, the goal is to create a flatter structure with a reduced number of command levels that better reflects how commercial and non-military organisations function. This would encourage greater cooperation and teamwork, but would not necessarily lead to a loss of control or reduced standards. Most important of all, such a reduction would allow technical credentials to assume a greater importance, with better recognition and reward. Not everyone wants to be a manager, but competent personnel still want their professional skills to be respected and remunerated.

As weapons and communication systems become more sophisticated, the technical competence of the people who operate them must be given a higher priority. Making professional and personal development a priority will improve technical standards. It will additionally give individuals a greater sense of fulfilment and achievement. Equally, it will allow people to leave the services and rejoin at a later stage. When skilled personnel can be persuaded to return to the services, this not only maximises a return on the initial investment to train them, but raises the standards of the whole force.

For some, these suggestions will be akin to heresy. But the purpose of this discussion isn’t to destroy or compromise the many great service traditions of the past, but to reflect contemporary society and the way the Armed Forces need to function to deliver effect.

_________________________________________

Notes:

[1] Source: Home Office data, November 2017

[2] Source: UK MoD, Armed Forces Quarterly Service Personnel Statistics, 1 April 2018

[3] Source: Quarterly Service Personnel Statistics,,UK MoD, July 2018 Edition [4] Source: Education at a Glance, OECD, 2011. Over the last 50 years, higher education has been more widely available to young people, with 81% of the population completing secondary education versus 45% prior to 1960; while 37% of young adults achieves a tertiary degree versus 13% prior to 1960.

[5] The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War. Gen. Charles C. Krulak, Marines Magazine. (January 1999)

[6] Source: UK Armed Forces, Biannual Diversity Statistics, 1 October 2017

The simple answer must be yes. Do the average service personnel understand the current structure? Streamlining is the only way forward on so many facets of the UK forces going into the future, and such a change could help new recruits to grasp the fundamentals of personnel grading. I for one, is baffled by the existing rank structure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just to add, ‘If it moves salute it,’ was a saying of an old uncle who was a Desert Rat!

LikeLike

Or if it flies Air Force gets it

On land, army

Floats, navy

Joint basic training for all ranks and 6 years reserve after service actually used.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My comments of 7th November at 8.03pm were written in haste and I now regret them. The comments below are a more reasoned approach to your article and I would appreciate it if you could delete my comments of 7th November and publish these comments instead.

The RN Lieutenant, Army Captain and the Flight Lieutenant are the bedrock of the British Officer corps. They are suitably experienced, knowledgeable, and dependable to be entrusted with ‘entry level’ command posts.

This however leaves a gap below them of younger, inexperienced, junior officers who are still learning their ‘craft’. They can’t be ignored. They are represented in the Navy by the Sub Lieutenant and Midshipman, in the Army by the Lieutenant and 2nd Lieutenant, and in the RAF by the Flying Officer and Pilot Officer. In the interests of reduction of the number of ranks and rationalisation I suggest they be merged in each service with the title of ‘Ensign’, a term which has been used in the past for junior officers. Below even them are the Officer Cadets which should also be included in the structure.

For many generations now between the Army, the Navy, and the RAF an acceptance has grown of parity of rank between the three services. For example the RN Captain, the Colonel, and the Group Captain have always been considered as of equivalent rank, as have the RN Lieutenant, Army Captain and Flight Lieutenant. These levels of parity in rank should be preserved throughout any change, or confusion and resentment will follow. If changes are to be introduced the names of the different ranks should remain the same as present as far as possible, again if confusion or even resentment is to be avoided. I have tried to avoid changes from the existing organisation as far as possible.

I am a firm believer in all three services having the same Insignia to indicate rank, in perhaps different colours to denote the service. I think this would remove much of the possibility of confusion between the services. For the Enlisted Ranks I agree with the idea of chevrons on epaulets or sleeves, although the Navy would not be pleased. For the Officers I believe a move away from the need to interpret the various symbols on Army Officers epaulets would be welcomed by the other two services, although the Army would not be pleased. I propose rings on epaulets or sleeves. Rings are so much easier to count. For Senior Officers I suggest using Stars like the USA. They are easier to count too. We have to work closely with our NATO allies. To avoid confusion in command our insignia should match theirs, for senior officers at least. If a US Admiral has four stars the British Admiral should have four stars too. (see * in the chart below)

In considering the opinions expressed above I would amend your chart as shown below.

Revised UK Armed Forces Structure.

Commissioned Ranks

O1 White Tab Officer Cadet Officer Cadet Officer Cadet

O2 1 Ring Ensign Ensign Ensign

O3 2 Rings Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant

O4 3 Rings Commander Lieut. Colonel Wing Commander

O5 4 Rings Captain Colonel Group Captain

O6 1 Star Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore

O7 2 Stars Vice Admiral Lieut. General Air Vice Marshal

O8 3 Stars Admiral General Air Marshall

Enlisted Ranks

OR1 None Ordinary Rating Private Aircraftman/Woman

OR2 1 Chevron Able Rating Lance Corporal Senior Aircraftman/Woman

OR3 2 Chevrons Leading Rating Corporal Corporal

OR4 3 Chevrons Petty Officer Sergeant Sergeant

OR5 4 Chevrons Chief Petty Officer Staff Sergeant Flight Sergeant

OR6 Royal Crest Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Warrant Officer

Compared with the present structure this proposal loses one level of Warrant Officer, and one level of Junior Officer. More controversially it lose the middle ranks of Lieutenant-Commander, Major, and Squadron Leader and the senior ranks of Rear Admiral and Major General and the Air Chief Marshall becomes an Air Marshall, which may not please the RAF. Time would tell if these arrangements could be sustained in cooperation with the rest of NATO, who retain these ranks. I would change the name of the Army Captain to Lieutenant to avoid confusion with RN Captains, but I see a problem there of perceived demotion.

I believe there are dangers in adopting civilian practices into the Armed Forces even if they work in peacetime. The Armed Forces live in a different world where for example the prospect of sudden death in action has to be planned for in advance through the rank structure. Great caution is needed.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your website doesn’t like copying microsoft word Tables. Sorry about that.

LikeLike

There’s a saying that the answer to any question posed in an article heading is always “no”.

The efficacy of any system for assessing performance, whether the rewards be rank or bonuses, is always dependent on its assessors. Whatever system you set up, you must be wary of those who will seek out how best to exploit it, be that prejudice of the assessors, the system or any number of other factors.

The number of available ranks is not necessarily linked to the numbers holding those ranks, either. If the problem is that we have more admirals than ships, is that a reflection of the number of types of admirals or something else?

As for renaming ranks, one could make a case for gender neutral titles but I don’t see the logic in removing existing titles for specialist roles that are already gender neutral.

LikeLike

As a former soldier , current reservist RAF and mod civil servant, I have often asked this question to myself. The current system actually leads to career progression where you have many senior ranks that do not play a part in command structure or battle deployment structure so they are then shunted into high level administration jobs.

This is both an efficient and a waste of resources as many of these jobs formal way below the expertise and experience of the person putting them. Why is this happening then? Well it is justification for the promotion ladder and utilizes somebody who has reached this rank. a classic example of this is the amount of senior RAF officers who are pilot qualified but do not fly an aircraft as part of their daily duties but still receive flying pay.

The current system of rank justaccentuates those who would career climb for pay and prestige. It is better to pay more money for longest serving officers even though they may be at the same rank as somebody who has served less years. This way you get to retain those who are experienced. the reserves do it by a form of bounty so there is no reason or me a bounty system should not be introduced for regular service personnel who sign on for extra years, regardless or not if they have been promoted.

LikeLike

Whilst I agree with a parallel rank structure across all three services if the artillery still wanted to call there corporal a bombardier and the guards a lance sergeant, then let them crack on with that. As long as other services recognise the rain kids and authority that comes with it it shouldn’t be a problem what they decide to call each other. The one I do have a problem with is corporal of horse, to anybody else this is a full screw or corporal, but I believe to the horsey types it’s a bit more important

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think this would work unless you eliminated the two tier career paths. The police that you use as an example have a single career path from constable to chief constable. If you wish to eliminate ranks a couple of the other ranks will have to go as well.

LikeLike

This is just change for change’s sake.

What have armed forces got to do with changes in corporate life?

I would be much more impressed if you had identified the most efficient Armed Forces in the world and then based your proposals on their rank structure.

United States? More ranks than us.

France? More ranks than us.

ISIS? No ranks at all as far as I know but would involve putting the Royal Army Chaplains Department in charge. Hmm… might work.

LikeLike

“What have armed forces got to do with changes in corporate life?” Quiet alot now. I work in a combined Civvy MOD and Uniformed environment and therir is an increased use of military officers in budget holding positions and as project managers. Rank is useful in so far as in confers resonsibility and authority of command but increasingly officers have had to advance up the rank structure to take on a role that does not have an eliment of command and control about it but does attract higher money due to the project they are invilved in, hence a wing commander in a technical training establishment that has budgetary responsibilities and a small mixed academic staff of civvys and service personnel. In the odeal world their coudl be a pay uplift that goes with any specialist educatioal skills without having to confer an increase in rank.

LikeLike

The author has not served therefore he lacks credibility, the current rank system is fine it has served us well.Remember you must give individuals an incentive to progress thus rank linked to pay is that incentive play with this proven system at your peril ,former RAF officer 36 years service.

LikeLike

The author has served, thank you very much. He spent seven years as an infantry officer in the Welsh Guards. He has also worked for several large global organisations, two of which, had (and still have) more employees than the RAF or Royal Navy. These commercial organisations manage to operate with lean management structures. Also, it appears that you may not have read the whole article, because, if you had, you might have seen that the reduction in the total number of ranks tries to avoid impacting mission command. Every formation, of whatever size, would still have the number of sub-unit commanders needed to ensure effective command and control.

Ultimately, the aim of reducing the number of ranks is to make the three services flatter, less rigid and less hierarchical, while making them more collaborative, and more efficient, but without losing sight of the values that make our armed forces unique. Leadership should never be about time served in the job, but the capability and qualifications you bring to the task at hand. Indeed, in an age of increasing technical sophistication, specialist knowledge matters more than ever.

LikeLike

Still the fact that just about every army in the world has a similar rank structure is probably not an accident. Other countries have commercial organisations with lean management structures too – but so far they have all resisted the temptation to get their armed forces to imitate them. We would need to identify why that is before taking a leap into the dark, otherwise we might find that we have put a spoke into the wheel of a system which works perfectly well.

LikeLike

Perhaps some of the contributors should accept that the article was written, as I presume, to provoke debate. At no point does the author presume to dictate that his thoughts on the subject is the only view worthy of consideration.

Incidentally, I can verify that Nick served in the Welsh Guards, as I was his platoon sergeant for about eight months in 1981 when he was platoon commander of No one platoon. He was also the sword of honour recipient of his intake at RMAS.

On the substance of the article, changes have been made to the structure of the military when it seemed necessary throughout its history, some more beneficial than others. Everything should be subject for consideration, nothing should be carried through without serious debate and consideration.

LikeLike

Hello Brian! How wonderful to re-connect with you via this blog! Thank you for your kind words of support not only today but all those years ago. You were a first-class platoon sergeant and thank God my father told me to listen to what you said. I learnt so much from you. I look back on my time in the Welsh Guards with great fondness. A superb bunch of men. When I left the Prince of Wales’s Company to go to the Guards Depot in early 1982, I never imagined you would go to war only a few months later. The men we lost in the Falklands will never be forgotten. I have got your email now and will reply separately. Cymru Am Byth!

LikeLike

Why simplify the rank structure at all?! The current rank structure of the British armed forces serves its purpose just fine!

LikeLike

I might add that during the whole of my 21 years’ service in the infantry I heard many complaints about just about every subject under the sun, with one notable exception – the rank structure. I never heard a single complaint about that, basically because it never impinged on anyone’s consciousness as a problem.

LikeLike

The simplified structure proposed completely ignores how units in the forces are organised, taking the Army as an example along with the fact that I’m most familiar with the Army:

A Battalion is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel. Why not a Colonel?

The Colonel is usually reserved for leading a Regiment however a Colonel can Command a Battalion if the “Colonel of the Regiment” is a Major General instead.

Battalions are split into Companies, typically 3-5 Companies in most nations.

All the Companies are individually commanded by a Captain except for either the most Junior Company or the most Senior Company.

This Specific Company is commanded by a Major instead of a Captain, this Major acts as the “Executive Officer” or “2iC” to the Battalion Commander. This role exists so that the Army don’t spend too long working out which Captain to be promoted to Lt. Colonel and the role works so that if the worst should happen to the Battalion Commander, say he is removed from his rank or is killed, the Major would instantly take over and a new Major be selected from the Captains then a new Captain selected and so on.

Each Company is split into Platoons which are commanded by Lieutenants and Second Lieutenants.

Only the most senior Platoon is commanded by a Lieutenant (First Lieutenant in the US Army)

That Lieutenant is again the “Second in Command” of the Company just as the Major is “Second in Command” of the Battalion.

The same system works in a similar way with NCOs however the ranks appear to be mostly kept the same in the proposed restructure.

I hope this shed some light on the subject and how it’s not as easy as just removing a couple ranks that have been in wide usage over nearly 300 years.

Thank-you for reading,

-Ollie | Military History enthusiast

LikeLike

Regimental and Company Sergeant Majors are not ranks but appointments in the Army. The rank is Warrant Officer Class One or Two. This allows other arms to Warrant Officers who are not infantry . For example REME have Artificer Sergeant Majors or Artificer Quarter Master Sergeants who are also Warrant Officer Class One or Two. The appointment changes with the different branches of the Army.

LikeLike

TThe top three most powerful militaries in the world today are generally reckoned to be 1. United States, 2. Russia, 3. China. I had a look at the rank structures of each of their armies (I’m not qualified to talk about any other service).

I’ve left out officer training ranks, specialist ranks and ranks only awarded in wartime (e.g. the US rank General of the Army).

The figures are as follows:

United States Army:

12 Non-officer ranks

10 Officer ranks (with exactly the same titles as ours)

Total: 22

Russian Army:

8 Non-Officer ranks

12 Officer ranks

Total: 20

Chinese Army:

9 Non-Officer ranks

10 Officer ranks

Total: 19

The British Army has 17 ranks (not counting Field Marshal which is now only awarded to Royalty or on retirement)

If these countries feel they need MORE ranks than we have, we would need to think very carefully before reducing ours.

LikeLike

Our small armed forced don’t need the 16-19 different ranks. Simplifying them to 12 is fine and eliminating confusion is good. I see nothing wrong with having a Sargent or Corporal in the Navy or having a Commander in the Army, or the Air Force following Army ranks like many other countries. My 12 ranks would be:

Private, Lance Corporal, Corporal, Sargent, Staff Sargent, Warrant Officier.

Ensign, Lieutenant, Commander, Captain/Colonel, Commodore/Brigadier, Admiral/General.

LikeLike

The problem comparing the Police to the armed forces is that a Chief Constable is, a Lieutenant-General, and is in command of a Division. The Police are not organised at a national level, unlike the Armed Forces.

Even with the Met, you have a Commissioner Rank who is, effectively, a Field Marshal.

But, re-organising the rank system of the UK armed forces is indeed necessary, with a one-track rank progression.

Evolution of the United States Military System thesis written by Kevin A. Deibler, PhD is actually a good example.

How I would break up the ranks would be as follows:

Other Ranks:

OR1/2: Private/Sailor/Aviator

OF3: Lance-Corporal/Able-Rate/Technician

OF4: Corporal/Leading Rate/Lead Technician.

OF5/6: Sergeant/Petty Officer/Head Technician

OF7: Sergeant Major/Chief Petty Officer/Cheif Technician

The next lot of ranks I would combine Warrant Officers and the Junior Officer ranks:

OF1: Lance-Captain/Sub-Officer/Lance-Officer

OF2: Captain/Chief Officer/Chief Officer

Senior Officers:

OF3: Lance-Colonel/Sub-Commander/Lance-Banneret

OF4: Colonel/Commander/Banneret

OF5: Colonel-Major/Chief Commander/Chief Banneret

General/Flag Officers:

OF6: Lance-General/Sub-Admiral/Sub-Ardian

OF7: General/Vice-Admiral/Vice-Ardian

OF8: General-Major/Admiral/Chief Ardian

National Ranks:

OF9: Sub-Marshal of the Forces

OF10: Grand Marshal of the Armed Forces (Chief of the Defence Staff)

For the Junior ranks, the term “Officer” can be used as a suffice for certain roles in the RN, and RAF, such as Pilot Officer, Technical Officer, Clerk Officer, etc. This merges the Warrant Officer roles with the Junior Officer roles.

I decided to use the originally proposed RAF ranks to be separate from the deputy and chief of the defence forces, respectively.

There will only be one Grand Marshal and 4 Sub-Marshals of the defence force, 1 for each of the 3 services, plus one as Deputy of the Defence Staff. The Sub-Marshals can thusly be called: Captain-General/Fleet Admiral/Air Chief Ardian, respectively. While they are head of each of the 3 services, they will primarily assist the day to day running of the Defence Staff, freeing up the General/Flag/Air ranks to command their combat elements as needed. The Fourth Sub-Marshal will then be the Vice-Marshal of the Defence Staff.

LikeLike

I read this article because I am interested in rank structure from a writing and world building perspective. It seems to me as ships and other military forces get more advanced some changes will need to be made. This is simply because of tectological advancements meaning to fewer crew being required. The Astute class submarines, for example, have 32 fewer crew than the predecessor. If this trend continues it could, in my opinion, lead to a confused system. Having fewer ranks might mitigate this somewhat.

LikeLike

Maybe you should have chosen a better example than submarines. The biggest British submarine in World War 2 was HMS Clyde which had a complement of 61, compared to the Astute class submarines’ complement of 98.

LikeLike