By Nicholas Drummond

The British Army’s Regimental System is often acknowledged as one of its greatest strengths, the source of an extraordinary esprit de corps that persuades soldiers to give their utmost in the most extreme of circumstances. But, it has also been criticised as one of its greatest weaknesses, an outdated institution that’s irrelevant in a modern age, an extravagant waste of money and a barrier to innovation. Whatever its pros and cons, the regimental system has been a fundamental part of the British Army since Cromwell’s New Model Army was established in 1645[1] and it remains central to the Army’s composition today, even though the number of regiments has declined significantly in recent years. In evaluating the regimental system, this discussion seeks to describe and define it, looking at its advantages and disadvantages, and to consider whether it should be left alone or evolve in some way.

Contents

01. An emotive topic

02. If it ain’t broke…

03. A bit of history

04. Do we need to reduce the total number of regiments further?

05. The question of uniformity and uniform

06. The need for cap badge mobility

07. Summary

01. An emotive topic

Every time a Defence Review comes along and a reduction in the Army’s size is proposed, there is an outcry. People object to cuts in overall troop numbers, but what really agitates them is the potential loss of famous regiments. In 2018, when the Government was contemplating its Modernising Defence Programme, it was suggested that the Parachute Regiment and Royal Marines should be merged into a single force. Letters to the Times and Telegraph were immediately fired-off. Local MPs received a barrage of angry missives expressing anger and disappointment. The blogosphere came alive with articles defending the existing structure, opposing fresh cuts and with suggestions of betters ways to rationalise the Army. Even a petition to Parliament was launched.[2]

(Above) The Parachute Regiment has become one of the Army’s most famous and iconic regiments, despite only being formed in 1942.

It should be immediately noted that merging the Paras and Commandos into a single unit is a very bad idea, not because they are sacred cows, but because combining them would halve the total number of elite troops that UK armed forces have at their disposal. Only someone who is militarily illiterate would allow a country’s best soldiers to be culled. It would also reduce the pool of talent available for UK Special Forces selection. What matters is not that the Royal Marines and Parachute Regiment perform different roles, and that these remain relevant to UK defence; it is that both units perpetuate the highest military standards. Their excellence percolates through to the rest of the UK’s Armed Forces. And, if the Army or Navy need to become smaller in future, then the quality of what remains must be preserved at all costs.

But this isn’t a discussion about protecting elite units, it is about developing a wider understanding what the regimental system is and what it contributes to the Army’s overall effectiveness. Before assessing the need to maintain the status quo or radically change it, what is significant about the debate is how emotive it is. Any discussion about Army regiments arouses passion and conviction out of all proportion to this topic’s importance relative to other military priorities, such as the acquisition of new equipment or new warfare doctrine. It shows that members of British Army, past and present, view their regiments with extraordinary affection and respect. They are treated as precious objects that need to be protected. The last thing any soldier wants is someone who doesn’t understand the system messing with it. It reflects the human truth that when people are comfortable with something, they dislike change for change’s sake. You have to give them a very good reason to change. You have to show them something better. But, even then, they will be reluctant to adopt something new.

02. If it ain’t broke…

When broaching the subject of the British Army’s regimental system, the default starting position of serving soldiers and veterans alike is: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The underlying belief is that the Army’s regimental system provides an approach to organisational structure and efficiency that has served the Army well for 360 years. Why change something that still manifestly works?

(Above) Cromwell’s New Model Army was established in 1645 was the foundation of the British Army as we know it today, including its regimental system. The new English Army was comprised of 22,000 soldiers, divided into 12 foot regiments of 600 men each, one dragoon or mounted regiment of 1000 men, and an artillery corps with 900 guns. Regiments wore coats of Venetian red with white facings, distinguishing them from their foes.

Going back in time to 1661 may be a good place to start. After the Restoration of the Monarchy, Cavaliers (Royalist commanders who had remained loyal to Charles II while in exile) were invited to form regiments to create a new standing army. Initially, these were the Horse Guards regiments of the Household Cavalry and the three original Foot Guards Regiments.[3] As the Army grew in size, it evolved. By the Napoleonic Wars, it was divided into four basic branches:

- Cavalry

- Infantry

- Artillery

- Logstics

Each branch or Corps was sub-divided into further groups or regiments, which had two or three battalions. These varied in size, but usually had between 300 and 800 soldiers, depending on role. Regiments were further divided into Company, Squadron, and Battery groups of 100 soldiers. Indeed, company-size groups can be traced back to Roman times when they were commanded by Centurions. These in turn were divided into Platoons and Troops. Size was dictated by how such groupings were controlled on the battlefield. Later, battalions and regiments were combined to create brigades, and brigades were combined to create divisions, and so on, to Corps level, and to Army Group level. These standard groupings have changed very little over the last century. They exist today, because they remain organisationally efficient and relevant to the way we and potential adversaries fight.

Over time, as the British Army fought in various campaigns, the regimental model proved to be practical and flexible. Individual regiments sought to distinguish themselves from their peer groups by establishing their own identity. The most obvious manifestation of this was uniform, but the attributes that underpinned a regiment’s culture became important. Its history, including battle honours, traditions and customs, and the type of people it recruited, all began to define a set of intangible associations that made it distinct from other units. Obviously, regiments that achieved greater success in battle were more highly regarded.

Today, regiments of the British Army consider themselves much more than a collection of soldiers grouped together to perform specific military tasks. They see themselves as families. They give serving soldiers and veterans a sense of belonging, of being part of an organisation that is bigger and better than any single person within it. The bonds of friendships within regiments, especially those forged during conflict, can be so strong they create a generational link between units and the families who serve within their ranks, from father to grandson. Very often the emotional connection is so powerful that soldiers who belong to a certain regiment consider its identity to be stronger and more important than the Army’s as a whole. They don’t join the Army; they join the Loamshire Fusiliers or whatever regiment their ancestors served with.

(Above) Today’s Army is comprised of 46 regular regiments.

(Above) The Army Reserve adds another 7 regiments to the total. There are also five British Overseas Territories regiments or defence forces, making a total of 58 regiments.

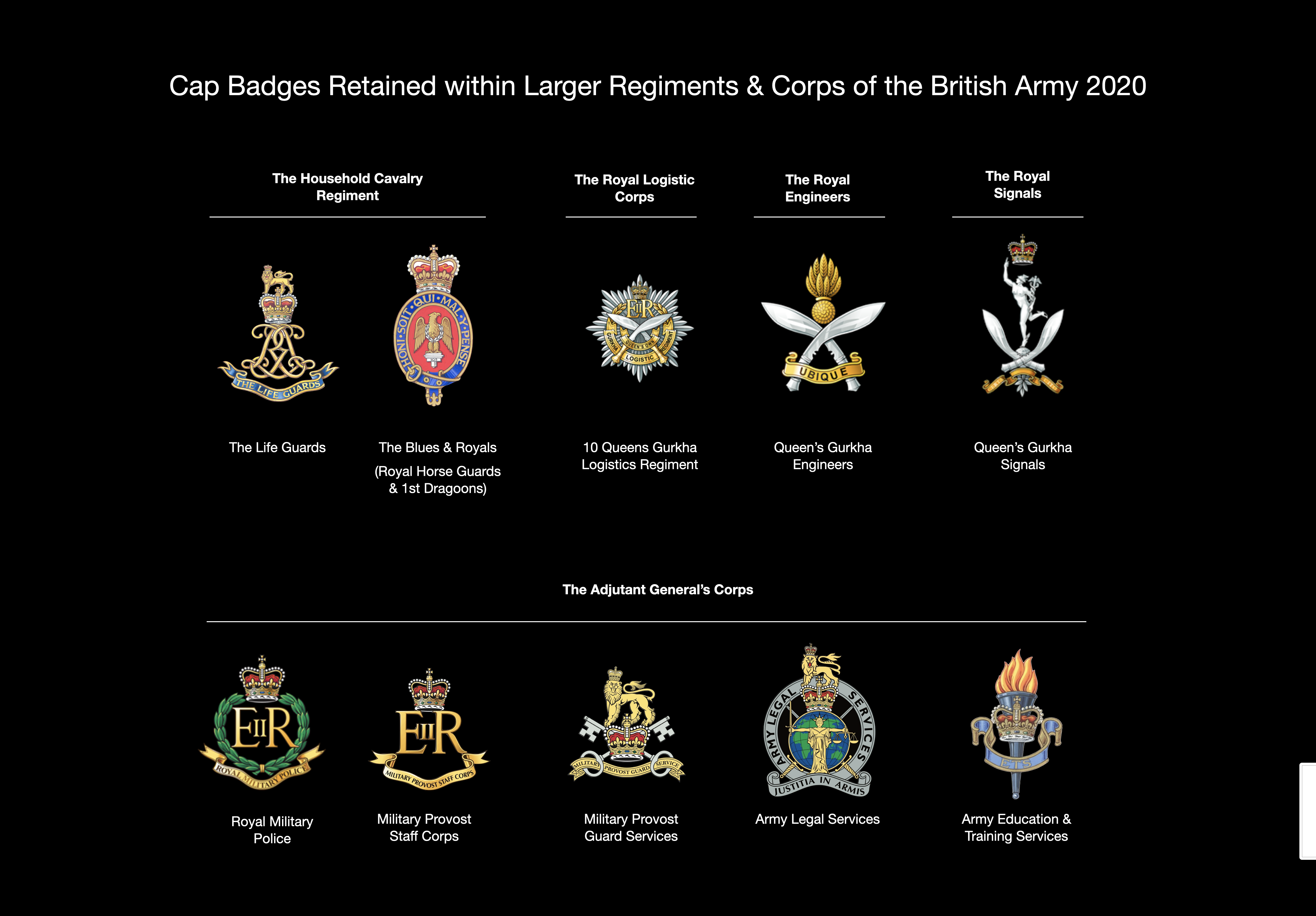

(Above) Within the existing regiments of the British Army, there are a further 10 cap badges that have been retained, creating a total of 68 separate regimental identities.

The strength of the regimental system is that when the chips are down, unit cohesion will carry the day. More often than not, soldiers will identify more strongly with the band of brothers (and sisters) fighting next to them than they will with a national cause, however worthy. Regimental identities reinforce teamwork, a sense of common purpose and shared values. It encourages soldiers to do things for the sake of their comrades and their regiment that they might never ordinarily consider doing.

If the Army values common standards to ensure combat effectiveness across the entire organisation, how can individualism or regimental uniqueness serve its higher goals? The British Army has deliberately codified its values and standards. These are a set of principles it believes every soldier should live by. Regardless of rank, regiment or corps, the Army expects every soldier to demonstrate: courage, discipline, respect for others, integrity, loyalty, and selfless commitment. Its standards for conduct are lawful, acceptable behaviour and professional.[4] If the Army’s intent is to set and maintain these cornerstones qualities across all units, does the regimental system facilitate or compromise the achievement of this goal?

The Army’s guiding principles do not stand alone; they are embedded within the core values of each regiment. Like the Queen’s Regulations, they set a standard that is followed by every cap badge. It is extremely unlikely that any regiment would adopt different standards or condone behaviour that compromises the Army’s brand, e.g. acting contrary to the Laws of Armed Conflict. What is different about the Army’s brand and the brand of individual regiments is that every regiment has a different emphasis. Each one believes in its own interpretation of excellence. Infantry regiments might prize physical fitness and endurance. Artillery and Engineer regiments might value intellectual rigour and problem solving. Regardless of the attributes that build a regiment’s character and personality, all share the higher values of the Army as a whole. The experience that different regiments offer can be compared to English Premier League football teams. All have a distinct identity, e.g. Manchester United, Chelsea, and Everton, but all follow the Football Association’s rules. Sometimes the reasons why people support one team versus another are totally intangible. The same is true of regiments. Another example is people working in the Tech Industry. Employees of Google, Apple, and Microsoft will find that each company offers a very different environment and culture, while essentially being identical types of business. Ultimately, choosing a regiment is about finding a home, a place where you interact with people who share your own beliefs, interests and ways of being and doing. This is good because it encourages friendship and loyalty. If you are going to put your life on the line, then being with people you like, respect and trust is essential.

(Above) The Charge of the Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was immortalised by Lady Butler’s painting. The regiment started life as the 2nd (Royal North British) Regiment of Dragoons. Through successive amalgamations, they adopted their nickname “The Scots Greys” as their formal title. They survive today as the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

The individual customs and traditions of regiments are often viewed as old-fashioned and irrelevant. In fact, they find their origins in standard operating procedures that historically made a regiment more effective in battle. Trooping the Colour (parading the flags of a regiment in front of its soldiers) was something that every regiment used to do. Today, we regard it as a quaint and colourful musical pageant, but it served a vital role by showing troops what the rallying point in battle looked like. Kit inspections may seem banal rituals, but they ensure soldiers carry everything needed to survive in the field. They also teach each soldiers to look after their equipment. Drills are repeated so that they become automatic, something you do without thinking about, because often you can’t think. So while the idiosyncrasies of different regiments may seem bizarre to the uninitiated, they are rooted in regiments codifying knowledge acquired through experience and often at great human cost.

We can summarise the benefits of the British Army’s regimental system as follows:

- Reflects the way Army units are structured and organised

- Helps to forge personal and professional bonds that enhance effectiveness in battle

- Builds strong identities that serve as a recruiting and retention tool

- Allows accumulated knowledge and historical achievements to be recorded and retained

For all its benefits, the British Army’s regimental system is seen by some as inefficient and problematic. They perceive it to be anachronistic and irrelevant to a progressive army, because it invests the organisation as a whole with too much emotion. Some regiments have more influence and power than others and may use it to resist change or obtain an unfair advantage. The argument: “we’ve always done it this way and it works” can be used as a barrier to innovation when change is genuinely needed. Historically, the reluctance of cavalry regiments to give-up their horses was seen as a barrier to modernisation in the early part of the 20th Century.

The regimental system can create petty rivalries that become toxic and counter-productive, e.g. when soldiers from Regiment A get into fights with soldiers from Regiment B and wreck local pubs. Tribalism can compromise rational and correct behaviour. When sub-standard performance or inappropriate behaviour is covered-up to protect the integrity of a regiment, a failure to address the problem damages the whole Army.

Regimental bias can cloud an officer’s judgement. Acting in the interest of your own group can prejudice the achievement of a higher goal. Then there is the question of whether someone is a better leader because they have served in Regiment A as opposed to Regiment B? Are officers whose careers have been built in combat support regiments any less capable than infantry officers? When loyalty to your own regiment blinds you to the quality of other corps and services, then it is counter-productive.

Within a system where identity and culture are everything, it can be difficult for people to move between different unit types. When officers at the top of the tree give preferential treatment to less capable officers from their own regiment or corps, this comprises a higher overall standard. Another example is when an officer from one regiment is sent to command a regiment with a different cap badge. An outsider may never be accepted, regardless of ability, because the regiment in question was never their home. Increasingly, we need to move officers and other ranks between different regiments to widen their experiences and improve their technical skills. If the regimental system becomes a barrier to career mobility, then it needs to be streamlined to reduce the culture clash between different regiments.

If mobility between regiments is desirable, how can it best be achieved? Is it even a realistic aspiration? For some, a more homogenous army would be more objective and efficient. For others, it would be throwing the baby out with the bath water.

There is also the sheer cost of supporting so many uniform variations. Different badges, buttons and dress uniforms can communicate a powerful identity, but sometimes the differences between different regimental identities can be so great that it’s hard to believe they belong to the same army. The idea that one regiment is inferior to another because its uniform is less distinctive is absurd. It’s simply another aspect of unhelpful emotional dimension.

The disadvantage of he regimental system can be summarised as follows:

- Promotes a slavishness to tradition (we’ve always done it like this) that can be a barrier to change and innovation

- Generates tribalism that leads to unfair bias, counter-productive attitudes, and toxic rivalries

- Restricts the freedom of personnel to move between units impeding knowledge development and the enhancement of the organisation as a whole

- High cost of supporting multiple uniform identities.

03. A bit of history

Today, the Regular British Army has 46 separate regiments, plus 10 further cap badges retained within larger regiments. There are 7 additional regiments that form part of the Army Reserve and 5 regiments / local defence forces that belong to British overseas territories and which are technically part of the British Army. This means there are 58 distinct regiments with a total of 68 different cap badges.[5]

In 1990, there were more than 100 separate regiments. Even though the Army had over 160,000 personnel at the time, this was still an extraordinary number of different cap badges to support. The 1990 Defence Review, Options for Change, seeking to cash-in on the “Peace Dividend” resulting from the end of the Cold War, led to the merger of 24 regiments. While some much respected names were lost, there were a number of other sensible reorganisations. The Royal Corps of Transport, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Pioneer Corps, Army Catering Corps and Royal Engineers Post and Courier Service, were all combined to create a single new regiment, the Royal Logistic Corps. This established a unit that has rightfully assumed a much more important status within the Army, and with a stronger sense of identity. More than anything, it has emphasised how important the people who sustain units in battle are. A second collection of administrative units was also grouped together. The Army Legal Services, Army Education & Training Corps, Royal Military Police, Military Provost Staff Corps, Military Provost Guard Corps, and the Women’s Royal Army Corp were all combined in the Adjutant General’s Corps. This new regiment has also been an unqualified success, even though it might have benefitted from a better name. At least, calling it the Adjutant General’s Corps was more imaginative than the Royal Corps of Administration.

(Above) British Army regiments before 1922, when 18 out of 31 cavalry regiments were amalgamated to create what became known as the “Vulgar Fraction” cavalry regiments. Today, just 9 cavalry regiment cap badges survive, plus the Royal Tank Regiment.

The 2004 Defence Review led to a further consolidation and restructuring of infantry regiments. In particular, the “Super Regiment” concept was born and nine new regiments were created:

- The Royal Regiment of Scotland was formed by amalgamating the Royal Scots Borderers, Royal Highland Fusiliers, Black Watch, the Highlanders, and the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders.

- The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment was formed by amalgamating the Queen’s Regiment and the Royal Hampshire Regiment.

- The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment was formed by amalgamating the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment, The King’s Regiment, and the King’s Own Border Regiment.

- The Yorkshire Regiment was formed by amalgamating the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire, the Green Howards, and the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

- The Mercian Regiment was formed by amalgamating the Cheshire Regiment, Worcestershire & Sherwood Foresters, and the Staffordshire Regiment.

- The Rifles was formed by amalgamating the Royal Green Jackets, the Light Infantry, the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire & Wiltshire Regiment, and the Devon & Dorset Regiment.

The Royal Welsh Regiment is single battalion regiment formed by amalgamating the Royal Welch Fusiliers and the Royal Regiment of Wales. Similarly, the Royal Irish Regiment combined the Royal Irish Rangers with the Ulster Defence Regiment.

The Royal Gurkha Rifles was formed by amalgamating the four pre-existing Gurkha regiments into two new regiments.

The Guards Division consisting of five separate regiments was, in effect, already a super regiment, so was untouched. The Parachute Regiment was also left alone, as were the Royal Anglian Regiment, and the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. One reason these regiments were not amalgamated was because all were successful in recruiting new soldiers.

All regular infantry regiments are now distributed between five divisions:

- The Guards Division (Foot Guards x 5 battalions)

- The Scottish, Irish & Welsh Division (Royal Regiment of Scotland x 4 battalions, Royal Welsh x 1 battalion, and Royal Irish Regiment x 1 Battalion))

- The King’s Division (Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment x 2 battalions, Yorkshire Regiment x 2 battalions, Mercian Regiment x 2 battalions)

- The Queen’s Division (Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment x 2 battalions, Royal Regiment of Fusiliers x 1 battalion, Royal Anglian Regiment x 2 battalions)

- The Rifles Division (The Rifles x 5 battalions)

Additionally, the Parachute Regiment has three battalions and the Royal Gurkha Rifles has two,. This reorganisation effectively creates seven infantry regiments.

When the above amalgamations were implemented, they were viewed as a sacrilege that would lead to the death of the regimental system, particularly among serving and veteran Scottish soldiers. With the benefit of hindsight, these consolidations can now be seen to have created new regimental identities that are just as strong as those that existed before. The Rifles has been a particularly successful creation. The way in which the new regiment leveraged the history of the old Rifle Brigade and Light Infantry regiments made it feel as if it had been around for ever, even though it only started life in 2007. The Mercian Regiment and Yorkshire Regiment have also been great successes. Both have been able to combine tradition with modernity. Overall, the consolidations were implemented with care and thought to ensure that the customs and traditions of the new regiments respected as much as possible those of the regiments they incorporated.

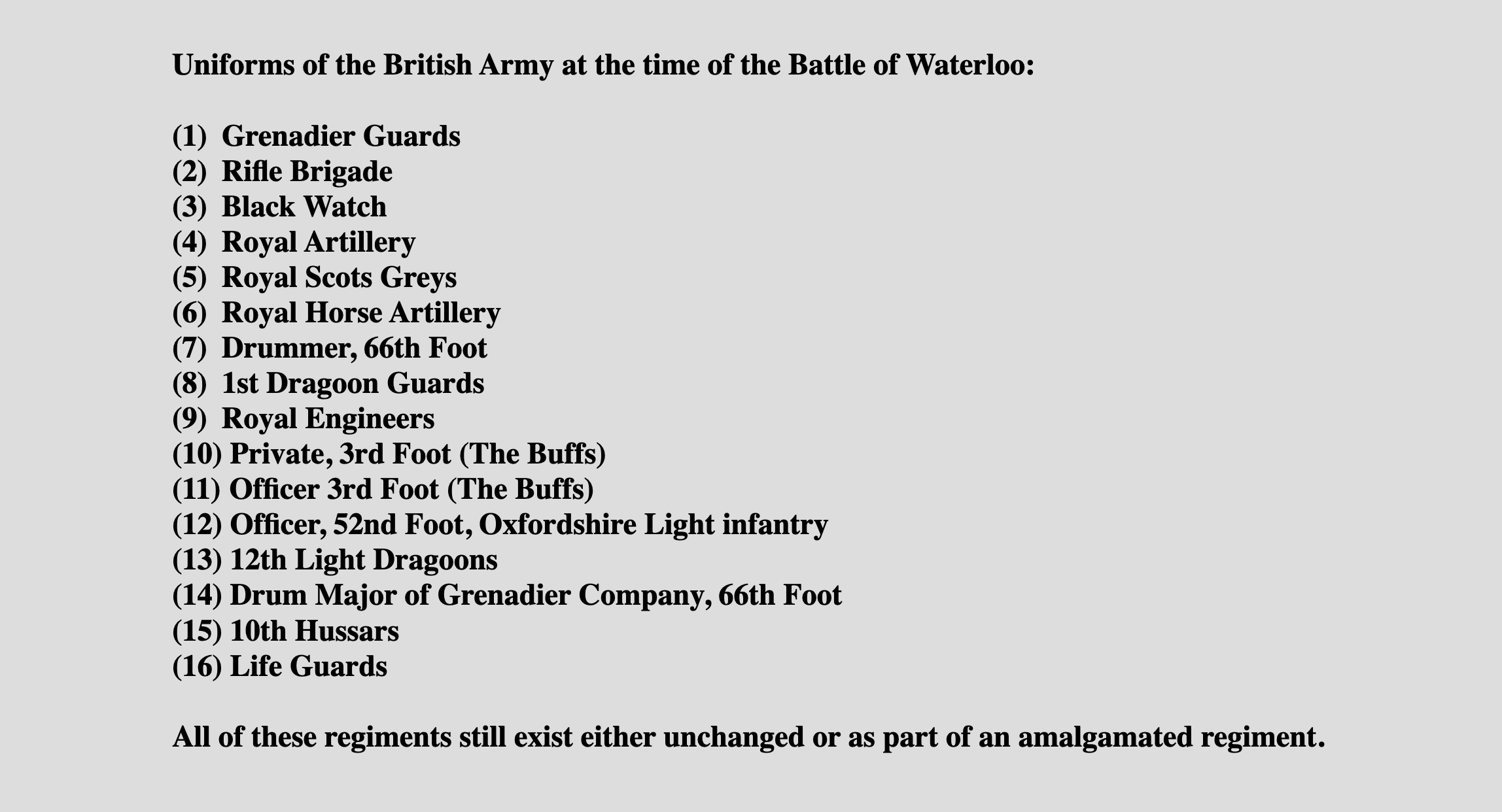

What is interesting about the 2004 rationalisation of cap badges is that the infantry now looks quite similar to how it was at the Battle of Waterloo, when it had four types of infantry regiment and they were all numbered:

- Regiments of Foot (Infantry of the Line)

- Highland Regiments (Infantry of the Line)

- Rifle Regiments

- Guards Regiments

This structure only changed when the county regiment system was introduced after the Cardwell and Childers Army reforms in 1881. When the Army expanded during the First World War, it grew to 96 different regiments with several battalions in each. Although a number of regiments were amalgamated during the inter-war years, the Army grew rapidly again as the Second World War approached. By 1945, the Army had approximately 2.5 million soldiers. Shrinking to a postwar peacetime structure, it was inevitable that many country regiments would be lost. At the height of the Cold War, the Army had 160,000 soldiers, but, when it ended in 1990, a rationalisation of regiments was overdue. Today, the Army has 18 separate infantry regiments with 33 battalions.

The same process of rationalisation was also applied to the Royal Armoured Corps. During the Second World War, when the number of tank regiments grew massively, cavalry regiments could barely keep-up with the need for new armoured units. After 1945, it was necessary to reduce the number of armoured regiments and this resulted in further amalgamations during the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. This continued the practice of creating what were often called the “vulgar fraction” cavalry regiments: 4th/7th Dragoon Guards, 9th/12th Lancers, 16th/5th Lancers, 17th/21st Lancers, 13th/18th Hussars, 15th/19th Hussars, 14th/20th King’s Hussars and so on. By 1990, there were just 15 different regular cavalry regiments left, plus the Royal Tank Regiment. Today, there are nine Royal Armoured Corps regiments (or ten, if the Life Guards and Blues & Royals are considered separate regiments within the Household Cavalry Regiment).

So, in reviewing how the Army has been reconfigured at various inflection points over the last 60 years, most if not all of the changes made have worked well. The Special Reconnaissance Regiment, the Rifles, the Parachute Regiment, and the Royal Logistics Regiment, are all less than a hundred years old, but have identities that are stronger than regiments with track records stretching back two centuries. Evolution has not destroyed the regimental system. It has made it simpler, more in tune with a smaller, peacetime army, while remaining true to the culture and ethos that make the Army a collection of highly functional regimental families.

04. Do we need to reduce the total number of regiments further?

The Army has not been as small as it is today since before the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s. It is hard to see it shrinking further, although there have been suggestions that headcount could be reduced to 75,000. Even if this were to happen, one or two infantry regiments might be lost, but, given the many priorities the Army has today, there seems no immediate need for another wholesale reorganisation of the regimental system.

If the Army has now reached, or is close to, the lowest possible headcount limit, any further reduction in the number of regiments could severely limit its ability to recruit soldiers quickly should the need arise. One approach to rapid expansion could be for all existing regiments to raise a second battalion. This would double the size of the Army quickly. Any further reduction in the number of regiments would frustrate future growth, if needed.

The Army’s current structure is lean and efficient. It has about 200 primary units (plus a further 40 headquarters, training centres, and miscellaneous company / squadron groups that perform specialist tasks. As noted above, the Regular Army has 68 cap badges, but the overall organisation by branch still exists. A further consolidation of regiments and corps could potentially reduce the total number of British Army cap badges to 16:

• Infantry

• Cavalry

• Artillery

• Engineers

• REME

• Signals

• Air Corps

• Logistics

• Administrative

• Chaplain’s Department

• Medical Services

• Music

• Special Forces

• Intelligence

• General Service

• Small Arms School Corps

The largest regiment in the Army is the Royal Artillery. This has three cap badges: the Royal Artillery, the Royal Horse Artillery and the Honourable Artillery Company (an Army Reserve unit). Most of its regiments are differentiated by numbers, e.g. 1 Regiment RHA, 29 Commando Regiment RA, 104 Regiment RA etc. The numbering system works well. The question is whether infantry and cavalry regiments need to re-adopt the same system, and whether it would bring any benefits. For example, the Guards Division could be turned into a super regiment with the five Foot Guards battalions renamed as 1 Guards, 2 Guards, 3 Guards, 4 Guards and 5 Guards, instead of the Grenadier, Coldstream, Scots, Irish, and Welsh Guards. Indeed, this nomenclature was not only used prior to Waterloo, but remains today as evidenced by the number of buttons on the tunics of each regiment. But what would the loss of their names achieve? Would it change anything?

If we went a step further and created a Corps of Infantry, with all regiments wearing the same cap badge and identified only by a number, e.g. 1st Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Regiment etc., we would still have 32 separate battalions. So long as we maintain a unit size of 650-700 soldiers, then the regimental system would remain relevant. If battalions needed to be reduced in size for any reason, then perhaps a further consolidation of cap badges might be necessary. The point is that numbered regiments would actually be no different from named regiments. Inevitably, a collection of numbered regiments would seek to differentiate themselves, which is how many of today’s regiments were born. Previously, they were all numbered Line Infantry regiments. For example the 42nd Regiment of Foot became the Royal Highland Regiment of Foot and then officially became the Black Watch in 1881. This title had been its nickname in Gaelic, reflecting its origin of being a collection of “watch” companies that patrolled the Highlands. It is now the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. If we had 32 battalions in a Corps of Infantry, it is highly likely that each would be given given nicknames that over time would create 32 new identities.

The same logic applies to cavalry regiments that form the Royal Armoured Corps. Previously, these all had numbers and were differentiated by being called Horse Guards, Dragoons, Hussars, and Lancers. We could revert to a numbered system, e.g. 1st Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Cavalry Regiment, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, etc. Like the infantry, over time, each regiment would add new nicknames, unofficial emblems and colour flashes to its uniforms to differentiate it. Would anything really change?

A simplification of regiments would vastly reduce variations in uniform. It would make the Army more homogenous and egalitarian. It would roll-up the history, tradition, identity and culture of hundreds of regiments, built over hundreds of years into a small number of sub-groups. Parachute regiment soldiers might wear the same colour beret as everyone else; their specialisation would be denoted only by airborne wings worn on the shoulder of their No. 2 Dress. The King’s Royal Hussars would lose their cherry red trousers. The Rifles would lose their dark green uniform and black buttons. The Guards would lose their bearskins and tunics. It would certainly save money, but would it be a good thing? It is difficult to see how any benefits of doing this would outweigh the disadvantages.

What this discussion really boils down to is the need for so many different uniform variations. Why should some regiments have elegant, even flamboyant orders of dress, when others have plain and more mundane uniforms? Is the desire of some people to simplify the regimental system based purely on uniform envy? If it is, wouldn’t it just be another form of unit rivalry and thus hypocrisy?

05. The question of uniformity and uniform

Other armies often remark about the extraordinary variation in British Army uniforms. When military conferences are held and the officers of different regiments congregate, people often joke that no two British Army officers are ever dressed alike and, if they are, then one of them is an imposter! Is the Army obsessed with uniforms? Probably. If so, is this a good thing or is it a desire for individualism that has simply spun out of control?

When soldiers joined the Army in the 18th and 19th Centuries, regimental uniforms were a great aid to recruitment. The more distinguished a uniform was, the better a soldier would look. He would earn the affection of women and the respect of his non-military peer group. This would increase his own sense of self-respect and instil a sense of pride in belonging to a particular regiment. As a result of this, it was believed that a soldier would fight better in battle. The Army romanticised war and serving one’s country, because this helped attract recruits. Many soldiers came from poor backgrounds and their uniforms often gave them better clothing than they had ever owned. Joining the Army was an opportunity to better themselves and their uniform was an integral part of this. Thus, the design and quality of uniform provided by a regiment was important because the better it was, the more likely it would be to influence recruits. Red was the obvious and ubiquitous colour for tunics. It achieved standout on the field of battle. (It also disguised the flow of blood.) Every regiment was allotted a “facing colour,” which is a secondary colour used on the tunic. Cavalry and Guards regiments typically had blue facings. Others had yellow or buff facings. Some regiments wore blue tunics with reverse facings, like the Royal Artillery. Embellishments such as gold epaulettes and contrasting colours, such as purple or green, added dashes of individuality. Headdress was an ideal item to customise. Tricornes, Czapka (four-corned cavalry hats), cocked hats, peaked caps, bearskins, busbies, bonnets, berets, and all manner of plumed metal helmets, made ancient battlefields extremely colourful. A further practical dimension of a distinctive uniform is that it made re-grouping in the midst of battle easier (a function also served by regimental flags or colours).

When soldiers joined the Army in the 18th and 19th Centuries, regimental uniforms were a great aid to recruitment. The more distinguished a uniform was, the better a soldier would look. He would earn the affection of women and the respect of his non-military peer group. This would increase his own sense of self-respect and instil a sense of pride in belonging to a particular regiment. As a result of this, it was believed that a soldier would fight better in battle. The Army romanticised war and serving one’s country, because this helped attract recruits. Many soldiers came from poor backgrounds and their uniforms often gave them better clothing than they had ever owned. Joining the Army was an opportunity to better themselves and their uniform was an integral part of this. Thus, the design and quality of uniform provided by a regiment was important because the better it was, the more likely it would be to influence recruits. Red was the obvious and ubiquitous colour for tunics. It achieved standout on the field of battle. (It also disguised the flow of blood.) Every regiment was allotted a “facing colour,” which is a secondary colour used on the tunic. Cavalry and Guards regiments typically had blue facings. Others had yellow or buff facings. Some regiments wore blue tunics with reverse facings, like the Royal Artillery. Embellishments such as gold epaulettes and contrasting colours, such as purple or green, added dashes of individuality. Headdress was an ideal item to customise. Tricornes, Czapka (four-corned cavalry hats), cocked hats, peaked caps, bearskins, busbies, bonnets, berets, and all manner of plumed metal helmets, made ancient battlefields extremely colourful. A further practical dimension of a distinctive uniform is that it made re-grouping in the midst of battle easier (a function also served by regimental flags or colours).

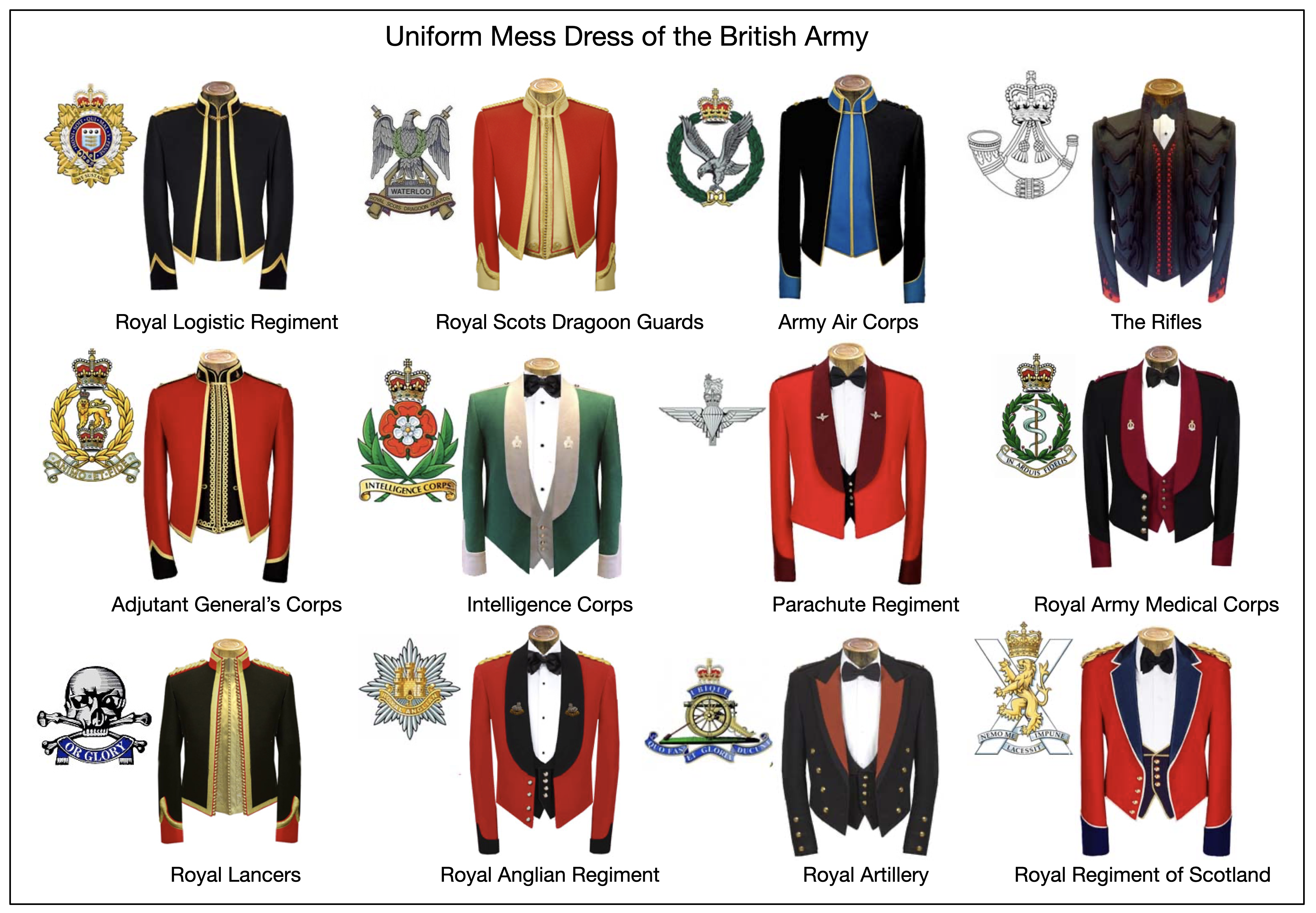

(Above) The Mess Dress of British Army regiments today (which is worn in the evening at formal dinners) shows the huge variation in uniform colour and design. Even newer regiments, such as the Royal Logistic Corps (top left) have created an elegant and stylish uniform.

Today, the British Army’s everyday uniforms are less colourful than they used to be. The No. 2 Dress, khaki service dress, is the primary formal uniform common to all regiments, but a stunning variation in style and design is still possible. The key differentiating elements are regimental insignia, buttons, badges of rank and headdress, while the Royal Regiment of Scotland still wears kilts. The Army still routinely issues a huge number of different uniforms including:

Full Dress – Ceremonial Uniform with Traditional Headdress (Scarlet)

No. 1 Dress – Temperate Ceremonial with Peaked Service Cap (Blues)

No. 2 Dress – Temperate Service Dress with Peaked Service Cap (Khaki)

No. 3 Dress – Tropical Ceremonial Dress with Peaked Service Cap (White)

No. 4 Dress – Tropical Service Dress with Peaked Service Cap (Tan)

No. 7 Dress – Tropical Barrack Dress with Beret (Tan)

No. 8 Dress – Combat Uniform with Beret in Regimental Colour (MTP)

No. 10 Dress – Temperate Mess Dress (for Sergeants and above)

No. 11 Dress – Tropical Mess Dress (White)

No. 13 Dress – Temperate Barrack Dress with Beret in Regimental Colour (Pullover)

This is probably too many orders of dress. It isn’t clear what it costs the Ministry of Defence to support so many uniform variations. Perhaps, three or four uniform types ought to suffice? But, if soldiers were to pay for their own uniforms, would it matter? The overarching point to make here is that reducing the total number of uniform types and variations is necessary and could reduce costs, but savings can be achieved without abandoning the regimental system.

(Above) The King’s Royal Hussars still wear the cherry red trousers of their forbears, the 11th Hussars. Their current ceremonial dress illustrates the extraordinary amount of uniform variation that exists within the modern British Army.

06. The need for cap badge mobility

An important concern already touched upon is the tribal nature of the regimental system and how this can make it difficult for someone from one regiment to move sideways to a regiment with a different cap badge. This is an important issue. As the Army becomes more technical and sophisticated in terms of weapons, equipment, C4I systems, and operational procedures, it is increasingly essential that officers and specialist other ranks gain a wider knowledge and experience of branches beyond their own. This means we need to encourage mobility between regiments and corps. Other armies already do this and it contributes to higher professional standards.

To enable mobility, it may be necessary to redesign career tracks so that all middle-ranking officers, senior warrant and non-commissioned officers are required to spend 12-24 months re-badged serving with another arm to widen their professional skill set. We should also require all senior officers to earn promotional credits by serving across at least two or three command appointments outside their own arm or branch of service. This would see infantry officers gain artillery, engineer and logistics experience, and vice-versa. At the very least, it would give officers a wider understanding of the many components that make-up the Army and better equip them for higher command.

It goes almost without saying that leadership appointments should be based on a meritocratic system rather than seniority based on length of career service. Would it not be fairer if only the most able officers across the entire Army commanded regiments, rather than regiments being led by less than ideal officers, simply because they are the best qualified officer within that particular regiment? In other words, what is really being proposed is that the further a solider advances in his or her career, the less important his or her starting regiment becomes. Instead of forming bonds with a single regiment, soldiers might potentially become close to two or three.

07. Summary

The British Army is often described as a “Reference Army.” This means that what it does is often used as a benchmark by other armies in establishing their own systems, operating procedures, equipment, and values. Despite its reduced size, the Army still consistently punches above its weight. It is well organised, highly disciplined and professional in all that it does. Its customs and culture are so powerful that they go beyond the Army. They are part of the British way of life. The strength of the whole is largely attributable to the many parts that comprise it: its regiments.

The Regimental system has been a significant part of the Army’s success throughout its long history. It gives individual units a strong sense of identity that differentiates them. It creates family ties that see successive generations serve within the same units. Regimental values instil a sense of self-belief and teamwork that enables a unit to perform better in combat. Despite their differences, British Army regiments are more alike than they might seem, because the Army’s core values of are embedded within each. Whether recently amalgamated or with an unbroken tradition, each regiment possesses a unique sense of self.

(Above) Despite being a new regiment, the Royal Regiment of Scotland draws extensively on the past. Its current uniforms are true to the colours, designs, customs and traditions of the regiments from which it was born.

Despite its manifold benefits, the system is not perfect. It can encourage unhelpful rivalries and create unfair bias. It can prevent mobility across different branches of the force. This is a problem, because a wider experience of different arms builds technical knowledge and skills that enhance overall professional standards. The Army may need to consider how it manages the career track of senior commissioned, warrant and non-commissioned officers, so that they are encouraged to move between units to gain specialist knowledge that equips them for specialist roles and higher command. Familiarity and closeness to other regiments will help break-down barriers.

The total number of regiments we have today, 58, is probably more than we need and there may be scope to combine some of these. For example, the four medical regiments (RAMC, RADC, RAVC, and QARANC), could probably be combined into just one Army Medical Services regiment with four different branches. The infantry’s 18 different regiments and the Royal Armoured Corps’ 9 different regiments may also be more than are strictly necessary. The seven groupings of infantry regiments we have today (Guards, Scots, Kings, Queen’s, Rifles, Paras and Gurkhas) seems to define a reduced number of seven future super regiments. We may also wish to streamline the Royal Armoured Corps to six regiments: Horse Guards, Dragoon Guards, Dragoons, Hussars, Lancers and the RTR. Even if we needed to reduce battalion and regiment numbers further, we would still need a total of 25-30 different regiments and corps.

(Above) It would be relatively straightforward to streamline the total number of cavalry regiments to six, with each regiment having two sub-regiments. Similarly, the super-regiment construct would allow the total number of infantry regiments to be reduced to just seven.

(Above) A rationalisation of cavalry and infantry regiments could reduce the Army to just 30 cap badges. This would not be an unmanageable or unaffordable number of unit types.

The Army is now as small as it has ever been, until the COVID-19 outbreak, it was thought that it was more likely to grow than shrink. In short-term, we may need to make further reductions even if there are more pressing modernisation priorities than another round of amalgamations.

The large number of uniform variations across different regiments is excessive. Reducing these through the increased standardisation of insignia, colours, and other elements of uniform design would ensure more consistency and save money, but it doesn’t need to compromise the regimental system. In the same ways that consumer brands need to be repackaged from time to time to ensure that they remain relevant to customers, Army regiments also need to evolve so that they stay in tune with a new generation of potential recruits and evolving nature of British society as a whole.

All things considered, the British Army’s regimental system offers more advantages than disadvantages. Ultimately, it makes the Army greater than the sum of its parts.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

[1] The British Regimental System: essential or outdated? Wavell Room blog, Dave X, August 2018.

https://wavellroom.com/2018/08/16/the-british-regimental-system-essential-or-outdated/

[2] Don’t merge the Parachute Regiment units with the Royal Marines Units Parliamentary Petition. https://petition.parliament.uk/archived/petitions/209564

[3] The Story of the Guards, Julian Paget, Osprey Publishing, 1976. SBN: 0850450780

[4] British Army Values & Standards booklet, Ministry of Defence, 2018.

[5] The British Army website. https://www.army.mod.uk

Great article, a really interesting read.

I would note that the psychology studies tend to show that loyalty tends to your oppo’s tends to by the key driver from Section to Company level (and maybe Battalion) – in other words the concept that you fight (and die) for the comrades you are closest too.

I know that while I am proud to have been Royal Corps of Signals, my real allegiance lay with 15 Psyops – my specific unit – which as an “army hosted” joint service unit had many regiments represented, plus RAF, Navy and Marines.

I think the size of the army now means that a Corps of infantry reduced to a small number of super regiments is the way to go. Putting RM and Para aside as “special operations” enablers, and based on Army desire to field two divisions, my fantasy orbat would be organized like this: 3 “divisions” of infantry, each with 3 brigades of 3 battalions. I have not entirely figured out a leanest way of doing ceremonial tasking, nor the garrison duties of Cyprus, FI, Brunei etc, thats for another post. However this structure would allow for rotation of 1 in 3 – one brigade is your high readiness in a deployable division (that has one of each type of brigade), the next is fully equipped but is training to achieve the high readiness status, and would take part in major exercises. The last is the “out of task” rotation, so 27 battalions – 9 in 3 high readiness brigades, 9 in 3 brigades working up and training, and 9 in 3 brigades on the garrison tasking, UK resilience roles etc

The Light Infantry – 9 battalions, manning 2 x “Light Strike Brigades” that replace 3 CDO and 16 AA , (but often work with RM Cdo’s and Para battalions as enablers).

The Foot Guards – 9 battalions, manning 2 x Strike Brigades. The “armoured infantry” (shock troops?) – yes I want 3 battalions of Boxers in each Strike Brigade 🙂

The Rifles – 9 battalions manning 2 x Mechanised Infantry Brigades (because I cannot bring my self to say Protected Mobility).

Only 3 slightly different uniforms ? Career mobility while staying in the same regiment (9 battalions) – the regiments are largely differentiated by their role (light, medium (mech), heavy (Strike)). The 3 “non-core task” battalions of each regiment would rotate the taskings too, so its not always going to a Light Infantry battalion in Cyprus etc.

There is enough differentiation to have esprit de corps – light fighters versus Guards, versus Rifles, but a much more sensible arrangement for a much smaller army. Regionality can be taken into account too – with 9 battalions in each “speciality” you can still have Scottish, Welsh, Irish, North East, North West, South East, South West, Midlands affiliated regiments.

Anyway, a pure fantasy orbat / organisational schema, but again, a very interesting article 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jed. Next up is your artillery article!

LikeLike

If the light division were to be made up of the Paras, Gurkhas and Marines then it’s basically ‘oven ready’ as Boris would say, you could do it tomorrow.

The combination of skills represented there would mean it could access 100% of the worlds surface, perhaps with the exception of active volcanoes.

A useful side effect of putting 3CDO on the army payroll would be freeing up billets on the navy side, so it could maybe afford to man the LPD’s. Navy could keep ‘navy’ things like 43 and 47.

Household Division for your heavy, King’s and Queen’s for your rifles in six regiments; little steps so the history doesn’t get obliterated.

LikeLike

Thats another way of doing it Nemo, but it does not allow you to lever RM in a littoral security role, which has already been decided will be their focus.

By taking what are currently light infantry units, (and that can include Gurkha’s if desired) and making them the core of the “light brigades” you keep the Para’s and the RM’s aside as specialists: they own and hone their specialist skills and knowledge and are available to act as enablers for both SF and the Light brigades.

So you want to use your Light Brigade to enter from the sea – add RM Assault Squadrons on their Landing Craft, add a Company of RM for Littoral security of the shipping and another Company ashore for other specialist tasks.

You want to fly your Light Brigade into theatre in A400 / C17 – use the Pathfinders and a Coy of Paras to drop in from C130’s to set a security perimeter around the destination airfield etc.

On a purely “inland” operation, you want to use your combat aviation brigade assets (CH47) to do a wet gap crossing operation, use a Coy or 2 of Paras in the Airmobile role, and some Marines to help with security and force protection on the river / estuary / lake your crossing.

Specialist enablers 🙂

LikeLike

Seems too sensible to ever come about!

LikeLike

An informative piece (and so colourful in places!), many thanks.

There’s something very real ale drinker about the military, when you showed your cap badge collection on twitter they immediately began arguing about order of precedence, seeing the

finished article you’ve included a rather lengthy section on what to wear and when.

My argument for big regiments and divisions.

Within larger regiments soldiers will form a close affinity with their battalion as well as their regiment, so it’s not necessarily a case of losing a family as gaining two, there’s also the possibility of a wider identity to be gained at division, something you can see with the US and as someone on another forum pointed out, some US divisions now have longer unbroken lineage and a better pedigree than British regiments.

I think it would be possible to bring antecedents and traditions along were you to look at mergers, if 2nd battalion needs to wear its beret backwards or sing to the regimental duck every Tuesday it’s not really a problem, all adds to the mystery.

A larger regiment evens out recruitment and day to day administrative issues and unless you’re dealing with army brats or the army barmy, or they’re trying for elite infantry, they’re not really going to know that they’re special until whatever regiment they end up in tells them that they are. Sorry if it’s an oversimplification but if you tell someone that they belong, that what they did was hard and that they are special, they’re probably going to believe you.

A large regiment reduces promotional bottlenecking and so helps officer retention, I’d go so far as to say that a large regiment would help retention of all ranks full stop if it were to incorporate more functions and trades for soldiers to move between as they aged or got bored.

You run the risk of your procurement and your doctrine being led by your existing composition, if you have nine cavalry regiments you will buy nine lots of cavalry vehicles to put in those regiments and then you will do cavalry things with them.

Numbering of regiments and battalions needn’t necessarily be an either or, you could have both, numbers just offer the possibility of a later adjustment, regiment survives, antecedents and traditions intact, seems to work for the marines.

Which leads me on. Watching and waiting on the marines to deliver future commando force and wondering what form it will take; if the army formed large regiments, if they were large enough and their constituent parts were small enough and flexible enough then it could embrace constant experimentation and improvement as routine.

LikeLike

This is a subject that takes me to the statistics again. Regular army full time trade trained strength at 1 January 2020 was 73,670 against a workforce requirement of 82,030. If the regimental families are a recruitment and retention tool then they’re not working in their current form.

I have data for individual infantry units from 1 July 2016, when the average strength was up at 95%. The following units were below average.

1st Battalion Grenadier Guards

1st Battalion Scots Guards

1st Battalion Irish Guards

1st Battalion Welch Guards

1st Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland

3rd Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland

4th Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland

1st Battalion Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment

1st Battalion Royal Regiment of Fusiliers

1st Battalion Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

2nd Battalion Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

1st Battalion Royal Welch

2nd Battalion Parachute Regiment

That’s a long list, but not a clear guide for fixing the system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Recruitment is a whole other area. This went badly wrong when we outsourced it to a non-military outfit. We clearly need to re-think how we do this. It is a problem that affects the whole Army and not just those regiments you have highlighted.

LikeLike

One of your 4 summary points in the article for the benefits of the regimental system was:

Strong identities are a useful recruiting and retention tool.

You now say recruitment is a whole other area. Historically, recruitment was closely tied to county regiments. Even outside the infantry there were ties like the Highland Gunners. Is that all relegated to history and strong identities are no longer a useful recruiting tool of the current regimental incarnations?

LikeLike

The County regiment system worked very well for recruiting. Of course, in the past, all recruitment was done at a local level. When the county regiment system started to wane, after WW2, all regiments found particular areas from which to recruit and maintained a presence in these areas. Often, Army careers offices were given targets: x number for the Green Jackets, y numbers for the Royal Engineers. It worked well. When it was centralised, it stopped working as it had before. It cost less money but prevented regiments from controlling their own destiny. Even so, the intangibles wrapped-up in different regiments’ identities still remain a powerful tool. Recruits still join because of family connections. As I say, we now need to re-think recruitment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apologies for my misspelling of Royal Welch, that should be Royal Welsh.

LikeLike

Paul

I think its interesting how the regional aspect works. When I was Navy I was onboard ships with people from all over the UK (and beyond occasionally). When at an RAF station for 6 months, they are the same, no such thing as regional recruiting.

Individuals might be more likely or not to find the regionality important. My Dad was conscripted in the late 1940’s – he was of the Palestine and Korea era. He was proud to be a Yorkshireman, but as he was 6 feet 4, they decided he needed to be a Guardsman. He was then sent to the Blues (later the Blues & Royals), part of the Household Cavalry. Would he rather have been in the Yorkshire Regiment – oh heck no, he loved being Cavalry! So everyone is different, and everyone’s motivation is different, but we find esprit de corps in different ways and places; if that means an element of regionality for soldiers who identify as Scots, Welsh or Irish, that might be factored in, but not the key factor ?

LikeLike

Jed

The Yorkshire Regiment was only formed in 2006 , well after your Dad’s time in the forces. Although, as you say he was conscripted and directed to the cavalry so no family history of A Yorkshire Regiment.

My Dad was conscripted to the West Yorkshire Regiment. The badge was a horse, but the regiment was not cavalry. I didn’t follow him.

My father-in-law was REME then RACD. My brother-in-law was RNR.

We are not examples of the regimental system bringing in recruits. The system had value at times for some but I think that is almost gone.

LikeLike

Ok, the problem as I see it is there is less flexibility with the current system. To keep regiments / battalions the battalion size has been reduced for political reason rather than military. I would say it time to start again with new larger regiments made up of battalions designed from scratch to be the best size / most effective number of sections etc . I suspect some battalions will be 800/900 strong, but that doesn’t matter because that is the best size.

Head down, hat on, waiting for the incoming.

LikeLike

Though not actually relevant, surely we can not ignore the elephant in the room when reviewing defence organizations. The COVID-19, the new phrase in the English language, following BREXIT, could have significant ramifications on the British Army? The two other services will obviously play their role if faced by another contagious virus. However, a viable ‘Virus Containment Strategy’ that will most surely be set up by the UK Government post, COVID -19, could have consequences on some Army structures, and their respective roles? The most significant change could be a substantial reduction in defence spending following an emergency budget, in order to address possibly the worst financial crisis since the 1700’s?

Maintaining the current MOD budget at pre-virus levels, is as likely as getting to the Moon on a bike, and the net damage to our forces is difficult to calculate. As seen with past defence cuts, many regiments have been either discontinued or amalgamated, and this must be a concern to such established units going forward?

We simply can not predict the future of the MOD’s strategic financial planning, but I fear grim times are ahead. In such circumstances, many current regiments will be vying for first place on the budget rankings, apart from possibly, the few historically safe national regiments.

Sorry for the gloom but a radical reorganisation of the NHS and future virus planning, will most likely cut deep into many government budgets, however, defence could be where the treasury knife will cut the deepest? Austerity, is not an option, having just exited an extended period of low scocial spending. My guess will be capital government establishments, of which defence sits perilously close to the Chancellor’s target zone.

LikeLike

I partially agree. The big thing is that Boris might not want to cut defense or risk facing his backbench. I think since I’m not up to date on my UK politics.

Even if defense maintained its current budget I think the army could still lose personal somewhere between 6k- 10k. This is because the the RN and I think the RAF have been asking for personal to man ships, aircraft, and relieve pressure on their current personal. This would also fit into the government’s focus on the RN and RAF after the Afghanistan and Iraq. It doesn’t help that the army is has a huge recruiting problem.

The one part about this article that I disagree with is dodging the question about cuts to the infantry. Even if the army retained its 82k headcount in needs to lose somewhere between 7-10 infantry battalions and I am not including the 5 battalions in the specialized infantry group. This decrease would allow the army to set up a 6th maneuver brigade and also have more enablers that including logistics, artillery, logistics, signals and electronic warfare, logistics, air defense, engineers, and logistics again.

LikeLike

Well, it’s kind of relevant if they need to look at a reduced headcount and radical restructuring.

Spending is sitting right on the 2% of GDP required by NATO, something the major parties have all committed to, so they can’t actually give them any less.

They could demand that they fix their 10 year budget black hole, or GDP could shrink, which frankly it probably will in the short term. Or both.

It would be interesting if the forces/MOD went super lean to meet a reduced 2% budget and rethought procurement. Then the economy recovered.

Maybe the poison we need? An end to our woes.

LikeLike

Sadly, I don’t believe any financial agreements made prior to Covid-19 on MOD budget, is worth the paper it’s written on. Critical financial measures will be necessary, if lockdown or restricted release lasts beyond August 2020.

The economic damage will be off the scale, beating 2008 and Wallstreet crashes combined. There is a real danger that the current financial World order, could shift heavily towards the East, as the US reels due to its distorted finances and horrendous debt. With the UK out of the EU and the US budget in tatters, the UK could find little comfort from that particular quarter? Some would sum up COVID-19 as a perfect storm, and I fear that will prove to be correct. One factor that will make life a little easier, is that the rest of the World will be in a similar predicament.

LikeLike

Hi, an interesting article on an interminable debate. I wonder if we’re simply not barking up the wrong tree. The element of tradition and cohesion is the real strength of the regimental system, but it doesn’t means the system can’t be modified without sacrificing these advantages.

The problem lies in the overall organisation. Armour doesn’t operate without infantry and artillery, etc. So why do continue with ‘Administrative Divisions’? why not simply create a series of functionally organised Corps, as is already the case with logistics and artillery, etc.

The Armoured or Manoeuvre warfare Corps could regroup all the relevant infantry and cavalry cap badges, would offer a specific ‘trade’ while at the same time allowing evolution within different roles. Likewise for a more ‘light infantry’ type corps, modelled around the Para construct, only with the additional emphasis on some form of motorised elements, specialising in long range operations and the jungle or urban theatres. The Royal Marines is already to a certain extent built on this model and has operated successfully for decades.

The cap badges then wouldn’t matter from a purely organisational point of view, but would enhance that sense of common goals across a diverse range of traditions.

I think its this multitude of overlapping formations and affiliation that causes the most damage now and stops budgets from being allocated effectively.

Just a thought.

LikeLike

‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it’….. I agree with this sentiment to a large degree, however what happens when the world changes and one is forced to change, irrespective of how good the previous approach was?

For example, currently brigades are currently built out of battalions and regiments (save 77X) each of which represents a cap-badge. When a sub-brigade all arms force is need then a battle-group is formed, multiple cap-badges but normally dominated by a core regiment/ battalion. One can say that this core unit in effect gives identity to the entire multi-cap badge battlegroup, e.g. 3 PARA Battlegroup.

However what happens if in future we end up forming permanent all arms units, e,g, rather than a battle-group of, say, 1,500 – 2,500 formed around a battalion, one has an all arms unit of around battalion size (650 – 750); e.g. a combined armoured infantry, armour, armoured cavalry, artillery etc. unit rather than a larger battle-group? In that case one would have a multiple cap-badge unit without a core regiment/ battalion at its heart from which to form as a foundation for its identity. Would not in that case the cap-badges become essentially branches of the army (in a similar way to which the navy has warfare/ engineer/ logistics branches) with the day-to-day identity, and loyalty, invested in the unit rather than the cap-badge?

I say this not as a prediction that it will happen but because we’re starting to see examples from around the world (US, Israel etc.) whereby the all arms notion is being pushed down to unit level and one can’t dismiss that it might come to pass, posing a challenge to the way the regimental system is currently used.

LikeLike

Sorry that I have come to the party late again but I just wanted to write in and say what an excellent article this is. Full of both insight and your usual common sense, it really does convey the truth about the British Army’s Regimental System. I agree with almost every point made.

Every Army regiment has its own ethos, created, as you say, through its history, traditions and customs, and the type of people it recruits. Such an ethos creates an esprit de corps, which “persuades soldiers to give their utmost in the most extreme of circumstances.”

I think that you are right too when you assert that people object to cuts in overall troop numbers, but what really agitates them is the potential loss of famous regiments.

On that very point, I just wonder whether there is any method whereby certain famous units could be withdrawn temporarily from the order of battle but their famous name be retained and re-introduced when the Army expands again, which I believe it will have to do eventually. We have lost such a number of famous regiments over recent decades but I believe that efforts have been made in some cases to preserve the name against the possibility of it being re-introduced I am not sure of my facts here, so if anyone could put me right, I would be very grateful. I think that a few years ago, the Green Howards were amalgamated into the Yorkshire Regiment and for a time retained their name as they became the 2nd Battalion of the Yorkshires. After a while, though, I think the Regiment was withdrawn from the orbat of the Regular Army. I don’t know whether it survives in any form in the Reserves. I think that there ought to be historical links to the old regiment for a name to be re-introduced “legitimately” and convincingly. Has such a thing ever happened?

I think too that you are right when you state that if numbered regiments were introduced, then “inevitably, a collection of numbered regiments would seek to differentiate themselves” (by adopting a nickname), “which is how many of today’s regiments were born.”

Agree too with your point that “Given that the Army is now as small as it has ever been, it is more likely to grow than shrink.”

All in all, an outstanding article.

LikeLike

Thanks, Mike. Your comments are much appreciated. I suspect it would be difficult to re-animate disbanded names so long after they were lost, especially when the last living members of these regiments are gone to the great parade ground in the sky. Inevitably, we are moving towards a streamlined number of seven “Super Regiments:” The Rifles, Scots, King’s, Queen’s, Guards, Paras and Gurkhas. Each of these regiments will be able to grow or contract as needs dictate. I can see each having 5 battalions in peacetime but growing to 10 battalions in time of war.

LikeLike

The Royal Artillery puts its batteries in suspended animation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Royal_Artillery_batteries

LikeLike

Greetings, good article.

Just a quick one from me (I know, a breath of fresh air)

I think we are going to see some big names going over the next few years, we have way too many infantry battalions that are still in existence purely because senior echelons in the army are dominated by infantry officers and veto any cap badge cuts. It is telling in the video that the army posted about 2020 refined that the first question was “is there any cap badge cuts?” not “will we loose X capability?”

From the top of my head (lazy google fingers) we have something in the order of 33 infantry battalions with a maximum of 10 in the war fighting division (4 strike 6 Armoured inf) as per 2020 refined. 3 are Para and a few are doing odd jobs but that still leaves the vast majority not being war fighting units.

The specialist battalions that are designed for soft power and to support and mentor other countries armed forces are much smaller than the standard battalions and are made up predominantly of NCOs with the Jr lads moving to the other deployable battalions for the first few years of service. This causes two issues for me, first the promotion potential of the infantry has now sky rocketed as a much larger portion will be NCO and secondly those battalions cannot be used for war fighting.

Specialist battalions are clearly there just to retain cap badges, what can a specialist Inf battalion do that a normal light Inf battalion cant do? except not deploy as a warfighting unit! but conveniently they are much smaller and cheaper. I agree with the idea, its great capability but why dedicate the majority of the army to it and not war fighting?

We are only ever going to deploy at maximum effort 1 Division (3Div) using 3 brigades with one left over for redundancy and to backfill. we should have a minimum of 12 battalions in 3 Div, 3 for each brigade. We should fold the battalions in 1 Div into 12 light Inf battalions (so no redundancies) and create 4 fully manned brigades that can still do the mentoring bit but can also deploy as a war fighting unit. That would reduce us down to 24 usable battalions plus 3 AA.

BV

LikeLike

I agree on specialized infantry, it’s something the rest of the army could do and would probably enjoy doing, those numbers could be pushed back into the other battalions to fill them out.

I think there would be scope for raising a ‘green beret’ equivalent just by giving SAS troopers with the right aptitude a tap on the shoulder before they RTU or are released into the wild, it would also keep their (frankly very expensive) skills to hand should we need them down the line. It could possibly be called the SOE, because reasons.

The other side of that coin you could raise a SFSG in a similar fashion because I think we’re already testing for it.

Talking to a fusilier he said most people in his battalion weren’t interested in trying out for SAS because it was a “face fits” organisation, that is, you could make the grade but not make the cut, because of the way it selects.

I suspect you could fill a regiment with those who made the grade and SF could select from that pool as and when required. So returning 1 Para to its brigade.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mentoring foreign solders is something we have been doing for years, and doing it very successfully I might add. Some jobs are more enjoyable than others, mentoring the Afghan forces was just awful with a constant green on blue threat, having to go work with some lads who just killed a bunch of British soldiers was tense to say the least. Whereas working with the Kenyans was great and we all learned a lot.

I think the SFSG route would be better mainly because it releases 1 Para back to fill its original role. I don’t think SOE would fly I’m afraid, I’m getting images of soldiers dressed as old ladies planting bombs on German railway lines.

BV

LikeLiked by 1 person

The name? I like it, evocative of derring-do, I was looking for something that went back a ways and it might suggest a role alongside 77 Brigade.

If I’m getting my recent history right then as the Middle East ramped up a problem emerged, SF were doing more door kicking and were struggling to cover covert surveillance and mentoring and so the SRR was born to take the pressure off of the one, so you might look at it as a restoration of capability as regards the other.

I think it’s wasteful if you’ve got guys coming out of SF with maybe a decade’s worth of training under their belts (particularly as regards things like linguistics) and professionally seeing the only way as down from there.

All the work is done, all you have to do ask is them if they’re happy to leave, or if they’d maybe like a quick chat; imagine the characters and the skills you’d be retaining. John McAleese got a job digging ditches after he left.

LikeLike

Two new “cap badges” weren’t mentioned (cap badges in inverted commas because, to my knowledge, their badges haven’t been created yet) – The Cayman Regt and the Turks and Caicos Regt both stood up this year.

LikeLike

In his excellent paper on the Regimental system Nicholas Drummond supports the Regimental system for its advantages but points out the following disadvantages:-

It can encourage unhelpful rivalries.

It can cover up sub standard or inappropriate behaviour.

It can blind people to the quality of other service units.

It can create unfair bias.

It can prevent mobility across different branches of the Army.

As an outsider (my suit was navy blue) most Army personnel would argue that I don’t have the necessary knowledge or experience to comment, but perhaps an outsider’s perspective might be less biased ? It seems to me that the emphasis has swung too far towards individual Regiments and away from the Corps and the Army as a whole. Uniform and badges have a subtle but enduring way of influencing attitudes. Changes may not have much influence on the ‘old sweats’ currently in service, but could well bring about changes in attitudes of new recruits and, over the years, of the whole Army.

As a means of shifting the emphasis from Regiment to Corps/Army I suggest that the Army adopts a standard cap badge, with a crown above a circlet of laurel leaves. The middle of the laurels should carry a Corps symbol, and at the base of the badge should be a cartouche bearing the abbreviation of the regiment within that Corps (E.g. 1RTR). You would have to introduce A Royal Infantry Corps. This retains the regimental system but it’s not so obvious, and presents a more uniform appearance to the outside world. It may even make it easier for soldiers to move between units. Similarly if No 1 Dress (Blues) is to be retained it should be identical right across the whole Army, also No 2, No 8 and No 13 Dress should all be identical across the service except perhaps for the colour of a beret and a Corps symbol on the upper arm. If Full Dress is to be retained there should be just enough traditional uniforms in each regiment to equip a guard and band, with the rest of the regiment in Blues, otherwise make Blues the ceremonial dress.

I would take the purely ceremonial units of the Household Cavalry and the Royal Horse Artillery out of the army proper and create a MOD owned private company from them using ex-servicemen and women; and I would leave the Guards intact as infantry but recruit ex-guardsmen into the same MOD owned private company to perform their ceremonial duties. Funding of this company would be less of a drain on the defence budget and could be recovered by charging the Mayor of London or other government bodies for their services. MOD ownership would enable the Army to keep control of the standards, and aid recruiting. Trooping of the colour would be carried out in Blues, not so impressive, but something the rest of the army could identify with, and much cheaper in the long run. Maybe in the long term trooping of the colour could be extended to other regiments? I’ll stop there as the abattoir is now full of sacred cows.

LikeLike

Some significant errors here – for one, it’s the Royal Logistic Corps not Royal Logistics Regiment. And if you think that it’s been an overwhelmingly successful amalgamation you might like to ponder what has happened to the functional skills once curated by the Royal Pioneer Corps and the Army Catering Corps. And you may wish to discuss whether there has been a loss in Supply and Transportation expertise with the loss of the RCT and RAOC. To my mind (as an RLC officer who started in the RCT) there has been a significant dilution of expertise. Big is not always better.

LikeLike

Hi greaat reading your blog

LikeLiked by 1 person