By Nicholas Drummond

Now that the dust has settled, it’s time to have a deeper look at the Integrated Review and evaluate its implications for UK Defence. This article is divided into two sections. The first is a review of the core strategy document: “Global Britain in a competitive age.” This is the primary Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy blueprint. The second part is a review of the Defence Command paper: “Defence in a competitive age,” which essentially explains how the aspirations of the defence and security components of the IR strategy will be implemented. This is further divided into a discussion of each of three primary domains, Sea, Land and Air, plus a brief discussion of Cyber and Space. Since this is a land power blog, the Army is the focus of this commentary. Readers interested only the land power element of this discussion should feel free to skip to the Army paragraph below.

1. Global Britain in a competitive age

The primary objective of the integrated Review was to reconfigure UK defence commitments around a more realistic and achievable set of foreign policy goals. This was necessary to ensure proper alignment between the things that we must absolutely do to protect UK interests at home and abroad with what we can realistically afford to do within our budget. Within military circles, defence academia and the wider armed forces community, there was an overwhelming sense that we were trying to do too much with too little. Therefore, a starting assumption was that instead of trying to do everything badly, we should identify the most important priorities and resource them properly, enabling a reduced set of commitments to be performed to the highest possible standard. The Government recognised that this was a sensible if not essential approach and got behind it.

A second driving force behind the Integrated Review is Britain’s need to reconsider its place in the world post-Brexit. The Government’s Global Britain agenda means we will look beyond Europe’s borders to trade more widely with Commonwealth and other international partners. This is not a rejection of Europe. It is about leveraging our renewed independence to unlock new opportunities internationally. We will definitely continue to trade with Europe, even if there is an inevitable increased cost of doing so, but the review recognises that Europe remains a vital ally, strategic partner and friend.

Thirdly, there has only been one serious attempt to re-set our defence priorities since the end of the Cold War. This was the 1998 Defence Review. Unfortunately, 9/11 and the resulting deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan ensured that its plans were never properly implemented. A decade later, we had become embroiled in what were widely considered to be two unwinnable wars. To make matters worse, the global financial crisis of 2008 caused an economic meltdown. When David Cameron’s coalition government came to power it embarked on a strategy of radical economic austerity to balance the budget. Consequently, the 2010 Strategic Defence & Security Review (SDSR) was not about managing UK defence needs, but cutting the deficit. The Defence Budget was slashed by £7 billion. Manpower was reduced by 20% and multiple equipment programmes were cut outright, reduced in scope or deferred. It was the most shocking reduction in UK military capability since the drawdown that occurred after second world war. The worst aspect of this was that there was no underlying strategy that made sense of what was left.

Fourthly, the economic impact of the Covid-19 is likely to be much more severe than the global financial crisis of 2008. While the consequences will not become apparent until the virus is fully under control, the level of Government borrowing has been significant. This will require austerity on a whole new level. Unavoidably, this means that the Integrated Review has had to be a cost-reduction exercise.

For all of the above reasons, there can be no doubt that a new strategic blueprint was well overdue. The result is a 111-page document, “Global Britain in a competitive age,” published on 16 March 2021. The first thing it provides is an overview of the national security and international environment to 2030. This highlights geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts, including China’s increased power and assertiveness. It notes the systemic competition between states and non-state actors, emphasising increased challenges to the established norms of the rules-based international order, and the fact that the distinction between peace and war has become blurred as authoritarian states resort to actions below the threshold of conflict to undermine democracy. It identifies rapid technological change, with scientific innovation and growing digitisation reshaping our societies, economies and relationships, as something that brings enormous benefits, but also that introduces further competitive challenges. Fourthly, the document lists transnational challenges, such as climate change, global health risks, international crime, the loss of biodiversity, and terrorism, as issues that require urgent action to ensure global resilience. Wrapped-up within this is the long-term geopolitical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, something that has completely changed our world since January 2020.

The high-level overview is used to construct an overall strategic framework that consists of four primary elements:

- Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology

- Shaping the open international order of the future

- Strengthening security and defence at home and overseas

- Building resilience at home and overseas

This is a framework that plays to Britain’s strengths as a nation. The document goes to considerable lengths to describe areas in which we punch above our weight. Britain has the fifth largest economy globally and is the second biggest spender within NATO, which means we make a serious contribution to global defence and security. We excel at scientific and technological innovation and are ranked fourth in the Global Innovation Index. We are a global leader in diplomacy and development. While the UK may not be a superpower militarily, we are ranked third in terms of our soft power influence. Many UK institutions contribute to this, including our education system, our legal system, and our system of government, which is truly democratic, open and accountable to the people it serves. We attract foreign investment, particularly in science and technology. The way in which we engage with international partners and competitors is always balanced and measured. Our culture and values make us a valued and respected member of the international order. So while we may not be superpower, we still wield considerable influence on the world stage.

As you would expect, the Integrated Review document explores the challenges we face in terms of state and non-state actors who represent risks and threats to our security, but equally, it identifies our key international partners and allies. Not surprisingly, China has overtaken Russia as the principal threat. This is attributable to its expanding influence and control in South East Asia, its “Belt & Road” initiatives in Africa and elsewhere, and intensifying competition for access and control of scarce natural resources. What is left unsaid, but is perhaps implicit within the Government’s overall evaluation, is the danger China now poses. It failed to provide timely warning of the dangers of the Coronavirus. It lacks transparency and refuses to cooperate with the global community in managing the pandemic’s impact. China’s manipulation of the situation to ensure it emerged sooner with a stronger economy is not how a global superpower should behave. Its failure to respect the Hong Kong handover agreement, its aggressive posturing in the South China Sea and, most seriously of all, reports of genocide committed against Uyghur Muslims in North West China, are all hallmarks of an inevitable metamorphosis from partner to competitor. China’s authoritarian regime has never really been questioned until now. The review is careful to use the word competitor instead of potential adversary, but we should be in no doubt that China has become both.

In describing the threat posed by Russia, the review document succinctly implies that the problem is not Russia’s people or culture, but rather its autocratic leader who respects neither democracy nor the rule of international law. Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Ukraine territory has alienated him. His response to sanctions is to actively undermine western democracies by all possible means. The use of weapons of mass destruction on UK soil illustrates an increasingly reckless regime. This makes Russia dangerous and unpredictable.

Coping with Russia or China in isolation would represent a major challenge, but together they exemplify a vastly more complex geopolitical environment. Closer ties between China and Russia are a further cause for concern. Other principal threats include North Korea, Iran and extremist terrorist groups. None of these are new, but they underline the fact that future conflicts are extremely hard to predict. Whereas we need to prepare for the most obvious challenges, we also need to meet unexpected dangers that leap unexpectedly out of nowhere. Avoiding conflict requires us to be proactive as well as responsive. This means that our defence posture must deter as well as being able to counter. Ultimately, we live in a world that is more volatile and dangerous than it has been at any time over the last 50 years.

Seeking to shape a future open international order requires the UK to form meaningful partnerships with our neighbours and longstanding allies. Not surprisingly, the document lists the United States as our most essential strategic ally. It also acknowledges the enduring importance of maintaining strong mutually beneficial relationships with our European neighbours, singling-out France, Germany, Ireland, Italy and Poland as tier one partners. Second tier European partners include Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey. There is recognition of the importance of the Five Eyes partnership between Britain, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Further afield, in the Indo-Pacific region, key partners include Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore. We also maintain strong historic links with Pakistan and India, with both countries playing an important role in containing Russia and China. Then there is the African continent with South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and Ghana, which remain an enduring focus for diplomatic efforts. In the Middle East, constructive relationships with Saudi Arabia, Israel, the UAE and Egypt remain paramount to avoid conflagration in the region. Distributed globally are the 54 members of the Commonwealth. This is not a complete list of international partners, but gives a flavour of massive diplomatic effort required to prosecute effective foreign policy.

The overarching strategy of the Integrated Review reflects “a tilt towards the Indo-Pacific while retaining a Euro-Atlantic focus.” Engaging effectively with international partners across the four strategic areas represents a huge political commitment, even before the defence and security component of this is considered. Note the word “tilt” is used rather than “pivot.” This suggests a recognition of the need to engage east of Suez, but not a wholesale realignment towards an enlarged permanent presence in Asia.

The foreign policy context drives the UK’s defence policy component of the document. The “Defending the UK and our people, at home and overseas” section has been divided into three high level commitments:

- Countering state threats: defence, disruption and deterrence. This includes defending the UK and our people at home and overseas; defence and deterrence through collective security; and countering state threats to our democracy, society and economy.

- Addressing conflict and instability. This involves the UK making an active contribution to conflict prevention and to prevent instability from creating power vacuums that allow security threats to proliferate.

- Homeland security and transnational security challenges. This includes countering radicalisation and terrorism; countering serious and organised crime; and strengthening global arms control, disarmament and counter-proliferation

These three strategic pillars reflect a policy of domestic physical defence of the United Kingdom, Overseas Territories and UK Dependencies, and the protection of UK interests abroad. They underline our commitment to the NATO alliance and operating in partnership with other member states. Further, they reflect an ongoing commitment to the United Nations and operating under the principals of International Law.

A core strategic tool remains Britain’s nuclear deterrent. An explicit statement of commitment to having a minimum, assured and credible capability in this area preserves Britain’s place as a Permanent Member of the United Nations Security Council. It is a commitment backed-up by the renewal of the Trident ballistic missile submarine fleet and by an upgrade to the missile system itself. This will allow us to increase the total number of nuclear warheads available for use from 180 to 260. In reality, the number of warheads possessed by the UK is unimportant so long as our multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) can reliably hit their designated targets. The new Dreadnought Class of SSBNs will be able to carry 12 Trident missiles. At the moment, it is not clear whether the current maximum of eight warheads per missile will be increased. If this is planned, then it would explain the UK’s intent to have a higher total number. What this announcement does do is send a clear message to China that anything it might do to trigger a major international conflict would end very badly for all parties if it led to a nuclear exchange. The threat of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), something which has kept the peace since the end of WW2, therefore provides an ongoing deterrent effect. The UK’s possession of nuclear weapons belies our relatively small size and limited economic power.

If nuclear weapons remain a weapon of last resort to counter peer adversaries, a corresponding capability is the regular and active employment of world-class national security and intelligence agencies. Britain’s resources in this area give us a tool that provides early warning of potential conflicts situations, as well as enabling us to pre-emptively counter terrorism and organised crime. This is increasingly dependent on technology for surveillance and information gathering. As we conduct our own “grey zone” initiatives, robust intelligence will enable timely and informed decision-making. Continued investment in this area supported by a trusted and well-established network of international relationships network reflect the fact that this is another area in which the UK excels.

Across the Integrated Review’s strategic framework, the UK is committed to building capabilities across all five domains:

- Sea

- Land

- Air

- Space

- Cyber

The scope of the review document is comprehensiveness and offers a polished discussion of the critical areas of defence and security. In doing so, it provides the desired connection between foreign policy and defence. What is alarming is the sheer breadth and depth of challenges we face. Ultimately, the Review defines a set of commitments, or a “To do list” that are expanded in scope rather than contracted into more affordable and sustainable objectives. This means the Integrated Review is a triumph of ambition over affordability – just like every other defence review of the last century. However, this does not mean that it has failed to achieve a fundamental goal. Rather it reflects an uncomfortable truth that any desire for retrenchment or withdrawal from a wider global engagement has been overtaken by events and this has happened much faster than we might have imagined.

Funding the aspirations of the Integrated Review will be challenging. Whether or not we can afford to resource every priority to the level we need is likely to be impossible, but it could well mean that we expand our armed forces beyond the scope of current plans. Ultimately, the Integrated Review is an outstanding strategic blueprint that will inform not only what Britain does as a result of having produced it, but also the defence activities of our friends and allies. Finally, it is a clear statement of intent that should leave potential adversaries in no doubt that any attempt to undermine or attack UK interests will be made to be as difficult and costly as possible.

2. The Defence Command Paper

If the Integrated Review document provides a strategic foundation, the “Defence in a competitive age” white paper, published on 22 March 2021, explains how the UK’s Armed Forces will evolve in terms of roles, tasks, size, structure, composition, and capabilities to deliver the Integrated Review’s objectives.

This document was less good. After reading just a few paragraphs it is apparent that large parts of the document were changed at the last moment. It doesn’t flow. It doesn’t feel joined-up, even though it echoes many of the themes of the primary document. The structure is more clunky and difficult to navigate. Much of the language uses impenetrable technical military jargon. When it describes a “permanent and persistent global engagement,” that is “catalysed by a digital network” to provide a “network of global hubs,” and you see that the plan incorporates the same overseas bases that we’ve used for the past 50 years, the effect is diminished. It is almost as if the authors forgot who they were talking to. It is a poor piece of communication, which frustrates its intent and its impact. More than that, major gaps and an overall lack of detail show that the implementation strategy is still a work in progress.

The core theme is an expeditionary focus enabled by a series of “lily pad” forward bases that offer jumping-off points to deploy larger forces. This plan envisages major operations being conducted in partnership with allies and heavily reliant on information technology, including resilient C4I systems, and interoperable systems.

A. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is fundamental to Global Britain and to delivering an expeditionary forces wherever they are needed. It is also essential to protect UK approaches, the North Atlantic and key trade routes. So, it was right that it came of out of the review in a strong position. The cost of renewing the nuclear deterrent is likely to rise above £41 billion, not only because we are building new ballistic missile submarines, but also because we are upgrading the Trident D5 missiles that they fire. Carrier Strike is also resource intensive due to cost of the ships themselves and the F-35 aircraft they carry, but additionally because they require such a huge infrastructure to support them, including escort vessels for protection. Escorts that sail with the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) cannot be used for other tasks, so plans for a new Type 32 Frigate and Type 83 destroyer to boost total ship numbers are welcome.

With a national shipbuilding programme at the heart of the Royal Navy’s future strategy, it will have one of the most formidable fleets in NATO by 2035. This will include 4 ballistic missile submarines, 7 attack submarines, 2 aircraft carriers, 2 commando LHDs, 24 escorts including 6 destroyers (Type 45 to be superseded by the Type 83), 18 frigates (including 8 Type 26, 5 Type 31 and 5 Type 32, which together will replace the existing Type 23), 8 offshore patrol vessels, and assorted smaller patrol craft. The Royal Navy’s current fleet of Hunt-Class mine counter-measures vessels will be superseded by a new type of autonomous mine clearance system. While harnessing new technology to save cost, this option ignores the fact that MCM vessels can also perform general patrol duties when not used in their primary task. A new multi-role ocean surveillance ship will arrive by 2025 to protect key underwater communications infrastructure. Investment in new ships will be matched by investment in new weapons, including a new anti-shipping missile and enhanced air defence systems. The Royal Marines will complete their transformation to the Future Commando Force. This will include two “Littoral Response Groups,” with one in Northern Europe and the other in the Indian Ocean.

There are three chinks in the Royal Navy’s armour. One is whether it has sufficient anti-submarine frigates. Eight Type 26 frigates are planned in total, which is barely sufficient to cover North Atlantic roles. The second concern is whether seven attack submarines is enough. There can be no doubt that Astute Class nuclear attack submarines are among the best boats of their kind, but they can only be in one place at a time. The third issue is the total number of F-35B Lightning II combat aircraft to be purchased. This has presently been capped at 48. The review committed to growing the fleet beyond this number, but did not specify how many or when. Each carrier can carry up to 36 aircraft, so this suggests a fleet of 72, plus a training squadron of 12. Irrespective of RN needs, the RAF also needs a Short Take Off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) aircraft to replace its own Harrier fleet that was retired early in 2010. A total purchase of 138 F-35Bs was anticipated, but with an acquisition cost still close to £100 million per aircraft and support costs that are more expensive than expected, we are unlikely to acquire more than 90 aircraft. Regardless of cost, the F-35 has fulfilled its promise. It is an extremely capable aircraft. Although we aim to acquire less expensive future aircraft that are more focused in the roles they perform, for the at least the next decade there is no serious alternative to the F-35.

B. The Royal Air Force

This brings us to the Royal Air Force which did not emerge from the review unscathed. The good news was reaffirmation of the Government’s commitment to the Tempest future combat aircraft, plus investment in a new remotely piloted aircraft system, the LANCA loyal wingman combat drone. The RAF’s ten Reaper RPAS will be replaced by 16 General Atomics MQ-9B Predator or Protector, as it will be called in UK service. We are unlikely to see the fruits of these development programmes before the mid 2030s.

The above initiatives were offset by a reduction in the Typhoon fleet of 24 aircraft through the premature retirement of Tranche 1 aircraft by 2025. This will leave a total of 107 aircraft to establish seven frontline squadrons and a training squadron. This means the RAF will have a total of 155 frontline combat aircraft. According to the IISS Military Balance yearbook, as recently as 2019, the RAF had 250 combat capable aircraft. So any decision to reduce the total number of F-35s ultimately purchased is likely to impact the RAF’s critical mass.

The RAF was forced to gap its maritime patrol aircraft capability for a decade after the Nimrod MRA4 was cancelled in 2010. However, the first of nine Boeing P-8A Poseidons is now entering service. It would be helpful if the total number could be increased to 12, but this is unaffordable at the moment. The RAF also intends to acquire the Boeing E-7 Wedgetail AEW&C aircraft to replace the Boeing E-3D Sentry AWACS, but only three will be acquired not five or six. This seems barely credible, making this the one serious shortcoming of the Defence Command Paper outcomes.

The fleet of 14 Lockheed-Martin C-130J Hercules transport aircraft fleet will be retired early, by 2023, despite flying as many hours annually as the Airbus A400M and Boeing C-17A fleets. It is not clear what will replace the Hercules in the Special Forces role, even though the A400M is now parachute capable. With Global Britain adopting a more outward looking defence posture, culling the number of strategic transport aircraft that can support deployed forces globally seems shortsighted. The RAF is rightly concerned about whether 22 A400Ms and 8 C-17As are sufficient to meet our needs.

A further 36 Hawk T1 training aircraft will be retired and replaced by virtual training; however, the type will continue to be flown by the Red Arrows display team. Nine of the RAF’s older Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopters will be retired, but the RAF is committed to maintaining this capability and intends to replace the entire fleet with the updated M-47F version. Given its overall contribution to defence, Chinook remains a high-value capability. The Puma fleet of 24 helicopters and several other disparate helicopter types will be replaced by a single new medium lift helicopter type.

While the above cuts have been balanced by investment in the new capabilities described above, plus the integration of new weapons onto the F-35B Lightning II, they amount to a net loss in RAF capability.

C. The British Army

As expected, the British Army has suffered most from Integrated Review rationalisations. Although the reduction in headcount from 82,000 to 72,500 was not as great as the 20,000 cut in 2010, and while the new cap will be achieved through soldiers exiting the service voluntarily rather than through redundancies, it is hard to see a 12% reduction in numbers as anything other than a serious loss of critical mass. To make matters worse, it is rumoured that all infantry battalions will be reduced in headcount to just 450 soldiers. If correct, this is utter madness. In comparison, Russia has a standing army of 280,000 and China 975,000. NATO armies need sufficient collective headcount to ensure they are not overwhelmed by a sheer weight of numbers. France has an Army of 114,000 and Italy one of 99,950, but Britain and Germany lag with armies of 72,500 and 61,000 respectively. (Source: IISS Military Balance yearbook 2020). As has been said repeatedly: modern conflicts unfold with unexpected speed and ferocity, so you go to war with the Army you have, not the one you’d ideally like. And, if you are not in the right place, at the right time, with the sufficient mass, you lose quickly and decisively.

Given severe resource constraints, the Army had to choose between a larger force modernised to a lesser degree, or a small force modernised more extensively. It chose the latter. Prior to the writing of the Defence Command Paper, there was already a perception that the Army 2025 plan had become undeliverable. Army modernisation envisioned two heavy armour tracked brigades, two medium strike brigades, an air assault brigade and various light role infantry brigades. Copying a US Army’s light, medium and heavy model, the plan aimed to establish a credible multi-role force capable of performing a range of mission types. By 2018, it was clear that the future plan was unrealistic and unaffordable.

The need to buy protected mobility vehicles for use in Iraq and Afghanistan had already hoovered-up much of the Army’s equipment budget. Meanwhile, a failure to manage the acquisition of new armoured vehicle types has reduced confidence in its ability to plan and implement its regeneration needs. Worse still, indeterminate success in Iraq and Afghanistan has caused many people to question what the Army is for. It is not clear that the Defence Command Paper has answered this, even though it emphasises an expeditionary focus with agile mobile forces.

There is plenty of evidence that UK Secretary of State for Defence, Ben Wallace, has been influenced by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The sight of Armenian armoured vehicles being hammered in large numbers by Azerbaijani loitering munitions will drive UK investment in similar high tech weaponry. While this is welcome, it has also led to doubts about the ongoing viability of heavy armour. This is a false pathology. Naturally, we need to take advantage of the new targeting opportunities offered by loitering munitions. But correspondingly, we need to address the vulnerabilities they create for legacy systems. Reducing the total number of armoured vehicles overlooks the capability they provide. History shows that units deploying in armoured vehicles suffer less casualties than those who deploy without protection. The real lesson from Nagorno-Karabakh is the need to invest in air defence systems that counter drones and loitering munitions.

The reduction in UK MBTs is therefore disappointing. The Army’s 227 Challenger 2 tanks was an ideal number that provided three regular regiments plus a training regiment. However, only 148 will be upgraded to the Challenger 3 standard. Worse still, the Warrior IFV upgrade programme was cancelled outright. This amounts to a net loss of 380 armoured vehicles and seriously undermines the Army’s ability to counter peer threats. At a time when we are reorienting our ground forces to fight high intensity conflicts versus near-peers, this seems counter-intuitive. This loss of capability disqualifies the UK for operating in partnership with the USA for operations that require an Armoured Infantry component, such as the Gulf War of 1991 and the Invasion of Iraq in 2003.

In defence of the decision to cut the Warrior CSP programme, it had been ongoing for more than decade without delivering. A production contract was meant to be placed in 2017, but reliability growth trials were still ongoing four years later. It is also worth noting that the Ajax reconnaissance vehicle programme has yet to deliver, despite being five years late and with ongoing technical issues. Similarly, Challenger 3 will only have a short service life, so better to save money on both MBTs and IFVs for now – but only if they are replaced by new vehicles subsequently. To a certain extent, a turreted Boxer could perform an IFV role, just as France’s 8×8 VBCI has replaced its tracked IFV. However, the Army has underlined an ongoing need for a tracked IFV, so we can only hope that the cancellation of Warrior is capability holiday rather than a total deletion.

Those responsible for the new structure have stressed the fact that the British Army no longer needs to be equipped to counter a massed assault across Germany’s Fulda Gap. This scenario previously defined the British Army of the Rhine’s doctrine and equipment, but is now redundant. Instead, it is more likely that we will deploy forces to Africa, Asia or the Middle East than Europe. Thus, the Army needs to be “expeditionary by design.” While this is accepted, if we find ourselves needing to go toe-to-toe with a peer adversary, tanks and tracked IFVs will remain essential. Nothing else provides the level of all-terrain firepower, resilience, persistence and shock effect. Combined arms armoured brigades remain the most expensive unit of land warfare currency, but cost alone should not disqualify them being part of the future force.

We certainly need lighter expeditionary forces that can be easily deployed and supported at reach, but an Army of Foxhounds, Bushmasters and JLTVs will not have the firepower and resilience to prevail. Therefore, we need a mix of capabilities: heavy and light. In essence, the new structure with Heavy and Light Brigade Combat Teams will deliver this but only to a limited extent.

In modernising the Army, we need place the right capability bets so that we are prepared for the most likely scenarios. This is easier said than done. Therefore, we need the future force to be easily reconfigurable. One advantage of the new Boxer 8×8 is that its mission module approach allows a force to be designed around the task at hand. Put a turret module on, and it can perform an IFV role. Put an APC module on it, and it can perform a COIN role. The Defence Command paper suggests that there will be an increased investment in Boxer. Given that it has high levels of protection, the ability to add an array of potent weapons and operational mobility, this is a welcome move. (Given the author’s close connection with KMW you would expect him to say this, but it also reflects his personal view.)

On the subject of Boxer, there was no mention of Strike doctrine in the Defence Command paper. But there should be no doubt that this remains a major part of the Integrated Operating Concept. At the risk of repeating this statement ad nauseam, strike is a way of fighting not a specific set of vehicles. The new structure suggests that the Army as whole is likely to become more modular and reconfigurable, so that it can perform different missions with equipment sets selected according to the threat, the mission, geography and terrain. This is excellent.

Fire and manoeuvre at brigade and divisional level is facilitated by armoured vehicles, but also by artillery and missile systems that deliver effect. During his speech to induce the Defence Command Paper, the Secretary of State for Defence pointed out that the reduction in headcount was necessary to fund new high tech weaponry. In particular, the Army will benefit from investment in new automated 155 mm mobile fires platform (to replace the defunct AS90 SPH), upgraded rocket artillery (longer range G/MLRS munitions), new ISTAR assets, non-line of sight (NLOS) anti-tank guided weapons, and new air defence capabilities. While these initiatives are much needed and highly anticipated, the paper was light on detail about which new systems were under consideration.

Infantry headcount will be reorganised around a new Special Operations Brigade with a new “Ranger Regiment” of 1,000 soldiers. This will be seeded by four infantry battalions with the Yorkshire Regiment, Princess of Wale’s Royal Regiment, and Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment all losing their second battalions. 4 Rifles will also be folded into the new organisation. It is possible that all regiments with a second battalion will lose it, including 2nd Battalion of the Royal Anglian Regiment. While the Ranger concept is interesting, it is hard to see how this unit will differ from the roles performed by the Royal Marines and Parachute Regiment. Far better if 16 Air Assault Brigade had been re-positioned as an Army Special Operations Brigade or Ranger force without a name change.

A new Security Force Assistance Brigade will incorporate four additional Specialised Infantry battalions with 1,000 soldiers, the same total as the Ranger Regiment. Each component battalion will have 250 soldiers. The overall restructuring plan suggests that infantry will be reorganised around four separate divisions, but it is not yet clear how this will work. Again, a better approach might have been to give this role to the newly formed Ranger regiment and retain conventional infantry mass.

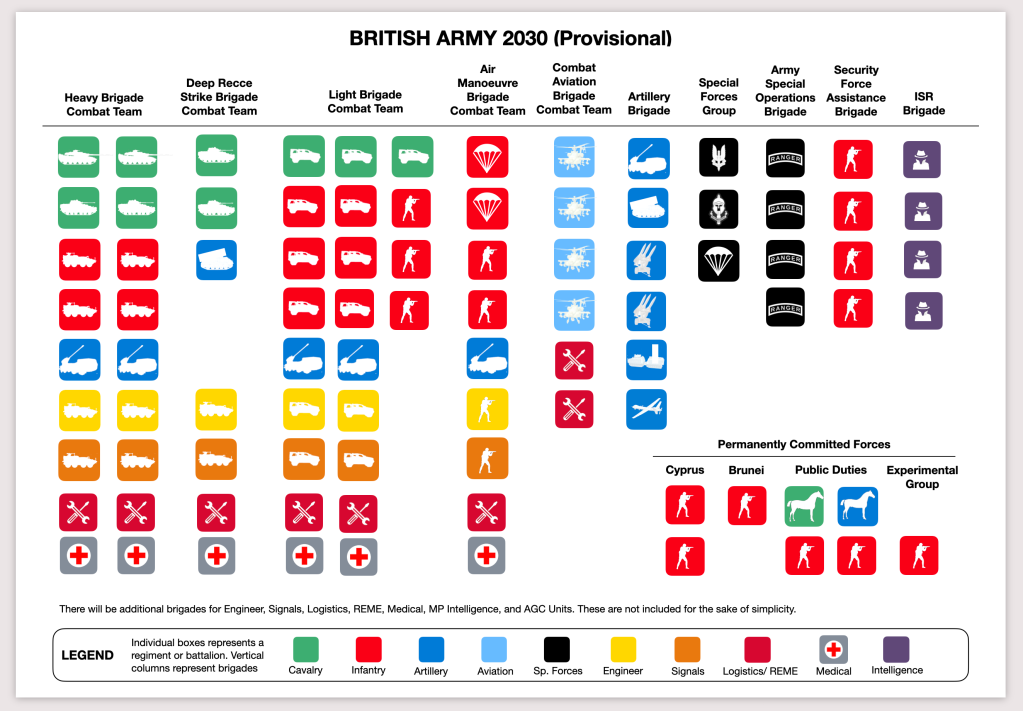

All combat arms will now be organised around “Brigade Combat Teams.” This is a US Army term used to describe combined arms brigades that deploy with their own combat support (CS) and combat service support (CSS) assets. The force will be divided into 3 (UK) Division with two Heavy Brigade Combat Teams (HBCTs) and a Deep Reconnaissance Brigade Combat Team (DRBCT), plus1 (UK) Division with two Light Brigade Combat Teams (LBCTs) and an Air Manoeuvre Brigade Combat Team (AMBCT). If this gives ultimately leads to the Army having two deployable divisions, or six deployable brigades, it will be a massive win.

It was further announced that individual combat brigades would have combined logistics and maintenance battalions as per the US model. So long as these are of a manageable size, they should enable the Army to generate more deployable forces that can be supported at reach. Again, the detail explaining how supporting arms, including engineers, signals, and medical units, would be incorporated into the BCT structure was missing. But, if this makes the Army more usable, then it is also a positive outcome.

In addition to the above, there will be a Combat Aviation Brigade Combat Team, and an ISR Brigade with the Special Forces group unchanged. It is not clear whether there will still be a separate artillery brigade, but this is assumed until we hear otherwise. Nor is it certain how many brigades in total will be deployable and what level of divisional support assets they will have. However, the emerging organisational structure already seems more coherent than the previous one, which featured too many ad hoc infantry battalions that would have deployed without armour or artillery support.

The Heavy Brigade Combat Team a Deep Recce Strike Brigade Combat Team structures come across as cobbling together the kit we have, rather than being a considered effort to resource an optimised structure. Three identical HBCTs and three identical LBCTs would be preferable, not least because this creates more efficient force generation cycles, with one brigade deployed, one preparing to deploy, and the third resting and regrouping after a deployment.

There was also very little on how existing equipment programmes would change. The timing for Challenger 2 LEP has not yet been fixed, despite Rheinmetall prematurely announcing that it had been awarded a contract. The Boxer acquisition will be accelerated. Ajax will seemingly continue. Warrior has been axed. But there was no mention of MRVP.

Future Soldier – Transforming the British Army

Some missing detail relating to the Army, and provided above, was added subsequently when a third paper “Future Soldier – Transforming the British Army” was published. This acknowledged that full exposition of the future strategy was being worked on. Called project Embankment, this is expected to be published in the summer.

D. Cyber and Space

Cyber and Space have become important new warfare domains. Investment in Cyber will include developing an offensive electronic warfare (EW) capability and a more sophisticated digitised C4I network and communications infrastructure. This will be delivered by the ongoing LE TacCIS / Morpheus programme.

Beyond the renewal of legacy capabilities, the Army envisages a hi-tech future with additional investment in autonomous systems, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data for the battlefield. Leveraging the UK’s leadership in science and technology, capabilities in the digital domain will enable us to compete in the “Grey Zone” below the threshold of conflict. Potential adversaries are already operating effectively in this space, initiating activities that fall just short of outright aggression. With an increasingly blurred distinction between competition and conflict, the Defence Command Paper emphasises the need to be more active and assertive in countering attempts to compromise democracy, the freedoms we take for granted and our way of life. While some of these tasks will be performed by the Army, many fall under the responsibility of GCHQ, the Government’s communications headquarters.

The Government said little about what it would do in the space domain. Activities in this area will likely include investing in satellite systems such as Skynet for communication and surveillance tasks. The need for secrecy means that detailed information is not readily available.

Summary

The reality of the situation we now find ourselves in is that we need to address a wider set of defence and security challenges at a time when we need tighten our belt. Part of the problem is that modernisation has been deferred so long that all three armed forces, particularly the Army, need more extensive modernisation than the budget now allows. The situation is like the roof of a house. Over time, holes appear. If they are repaired on an ongoing basis, the cost is manageable and the roof will last more or less indefinitely. But, if the roof is not maintained, existing holes get bigger and more appear. If nothing is done, you eventually reach a point where the whole roof needs to be repaired. This is always much more expensive than ongoing maintenance.

Although £24 billion of extra money has been allocated to defence, much of it will be used to ensure that existing plans are successfully implemented, rather than funding a further expansion in new capability areas. Unavoidably, we have been forced to reduce costs. This has required us to make difficult choices. Faced with the binary decision of whether we conduct a reduced range of modernisation initiatives across the existing force structure or implement a more extensive range of initiatives across a reduced force structure, the integrated Review makes it clear that we are following the latter strategy.

Given that the Ministry of Defence had been given two years to develop its future strategy, it seems strange that Defence Command Paper was not complete and was changed extensively at the last minute. All things considered, though, the question that has to be asked, despite the gaps that still exist, is defence in better shape now than it was before the integrated Review?

The answer is that the 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy is a quantum leap above the 2010 and 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Reviews. It is also superior to the 1998 Defence White Paper. All in all, it does an excellent job of providing a strategic narrative that sets UK defence and security priorities. However, the Defence Command Paper is not yet a proper implementation plan. To judge its success, we will need to wait until Project Embankment publishes its recommendations.

With the global geopolitical environment evolving rapidly, there is a possibility that the latest defence review will again be overtaken by events, so regardless of the priorities set today, we may need to adapt the plan before it is even implemented and quite possibly move in a different direction from the one we anticipate. However, as things stand today, Britain still possesses an extremely potent array of military capabilities.

In 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm II dismissed the British Army as a “contemptible little army.” Although it numbered only 250,000 soldiers compared to Germany’s 960,000, it was well-equipped, well-trained and highly professional, having learned many hard lessons during the Boer War. Despite its small size, it punched well above its weight. The contemporary British Army is also comparatively small, but equally well-trained, well-equipped and professional. Potential adversaries may still consider it to be contemptible, but, when all is said and done, it remains a force to be reckoned with.

Excellent article Nicholas, and I agree with your assessment overall.

Couple of minor points: you have the current spec infantry battalions in both the rangers and operations regiments, they can’t be in both. Also not sure where you have got 8 destroyers from but welcome if true.

As for the army. I think it is a real missed opportunity.

I agree with you that we need 3 brigades to generate a single brigade on an ongoing basis and I do wonder how we enhance harmonisation and make the army an employer of choice. So if we need heavy, strike and light, we need 9 brigades or 45k people.

A US BCT is circa 4.8k personnel, including air and I would like to see this happen at the brigades and divisional level, a US ABCT has 48 Apaches I believe, so I guess we need to buy more if we are going to deliver. What 8 really worry about and gen Carter has form here, in using US terms but not following up with the same equipment and support levels, and let’s not forget that in recent engagements it has been estimated that British forces are 12% more likely to be injured or killed as their US counterparts, which potentially linked to equipment shortages and failings.

So brigade combat teams are great, as long as they are fully resourced and equipped, they are death traps if they are not and they are certainly not cheap, but they can be potent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always laugh when the Army top brass say that the Army is “expeditionary”. They must use a completely different definition of expeditionary. There are notionally 8 expeditionary brigades, but that includes the 4 brigades of 1 Div, which would be hard pressed to mount an expedition to the local corner shop to buy a pint of milk. One of the armoured infantry brigades is now in experimentation mode, so that leaves just 2 armoured infantry brigades plus 16 Air Assault. In reality, it’s only really the latter that actually counts, because even the armoured infantry brigades would need some customization to get on the road. Perhaps moving to the BCT format would help, but I don’t understand how modularisation will help if there’s only one of each type of formation. It works for the US Army, because they have buckets loads of brigades to choose from. The US Army has more *types* of BCTs than the British Army has actual brigades (excluding all the non-deployable single arm brigades). A better approach for the British Army, in my opinion, would be modular regiment combat teams, allowing brigade-sized formations to choose from a pick-and-mix of combat, ISTAR, combat support and logisitic RCTs.

LikeLike

A good piece, thank you as always.

A huge anti-climax in my humble opinion, we were promised a step change and largely got plod on.

It raised issues around credibility, equivalency and competence for me; special forces and intelligence are already actively competed within the UK to a high level and actually are ‘world beating’ as is, saying everyone will be special does not make it so.

BCT’s: if you’re going to use those terms then the US is going to want to see something recognizable.

Loitering munitions rang alarm bells, a so called reference army being informed by a third world scrap doesn’t inspire; their take away should have been defence against a proliferation of such devices, incorporating the good and a focus on the next step, you can kind of visualize the older officers just getting this ABBA thing while the younger ones are shaving Mohicans.

As I’ve suggested previously I think general Rangeryness could have been achieved by expansion through the churn surrounding current SF.

I think the UK could have offered Security Assistance through a regiment recruiting from Commonwealth countries to give a multinational skillset and optic as well as providing an enviable linguistic resource to draw from.

And I think they should have gone with specialised divisional structures to push out tactical battlegroups, the smaller the groups the better they could be trained, managed, resourced, readied and deployed. Gotten over the regiment thing, maybe even gotten over the battalion thing. To that end, integrated reserves would also seem the wrong direction unless it’s specialists providing unique insight.

F35 should just go to the navy at this point and RAF should focus on Typhoon/Tempest with LANCA and developing a long range strike capability with LANCA and Voyager, which I’d suggest would be kind of a freebie and another string to our bow.

Yes, where is MRVP?

LikeLike

A this point the navy is 10 plus years away from being able to operate a force or say 60 F35 without RAF personnel. The fixed wing bit of the FAA is very small.

LikeLike

Ah, I see, thank you.

With the near certainty of a reduced buy, it seemed logical to me to compartmentalise the surged carrier ‘strike package’ of 36 (assuming active airframes might reflect that) and have the RAF focus its efforts elsewhere.

But no matter.

LikeLike

Hi Nicolas, thanks for the great article.

I think that these documents are a real mixed bag. Some of the news is terrific. Investing in new technologies such as cyber, especially if we’re going to pretend the British battleforce of the future is going to be networked and datacentric, is an absolute must. Still, I hope we have viable plan Bs, just in case the lights go out…).

The Navy information is very encouraging, and seems in tune with ambitions and the need to cultivate an effective defence industrial base. Likewise for the airforce: Tranche 1 Typhoons were an obvious and intelligent cut, and thinking ahead with Tempest is prudent and equally good news for the aerospace defence industrial base, especially given the reliable international partners that are joining the project with their different areas of excellence, and this is particularly reassuring given the FCAS calamity unfolding here in France and Germany. I agree with you though, it’s a pity to loose the C130s given the “global” and “light/agile” emphasis in the strategy paper. But a semi decent number of F35s, along with properly updated Typhoons, is all-in-all a positive story.

But the Army…

I don’t know whether to cringe, cry or scream. where are we going? You read one good thing: we’re going to be expeditionary, agile, lethal and light. Then you read “we’re keeping an obsolete tank fleet that’ll cost a fortune to revitalise (a veritable pig with lipstick), but not enough to create serviceable armoured formations, and, oh yeah, at first we’re going to send in our tanks into battle with an IFV that is not only even more obsolete than our tanks, but it won’t have a decent gun on it…and then (just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse), we’re going to replace that scrap with wheeled vehicles…back to unmanageable, incoherent tracked/wheeled formations. Oh, and we’ve also created a new concept to fit our increasingly irrelevant Ajax fleet into: deep strike reconnaissance! Ta daaa!

I know I’m going against the grain, but for us, to all intents and purposes, armoured maneuvre warfare (MBT-IFV-style) is DEAD. we can make no meaningful contribution based on the numbers announced, to NATO or anyone else in this domain anymore. So why do we not just move on, and develop a new way of fighting? One that is in line with our Strategy (there are many other ways that we can help maintain our NATO commitments). I think reducing numbers to concentrate on better resources is a good thing, even though we certainly loose resilience. But the current proposition is absurd. we should focus on expeditionary (we are very good at it), we should focus on modernity (this is what all the investment in tech is about); we should better exploit the structures we have and that few of our neighbours can enjoy (I agree totally with you that the Paras/16AA are already the basis of our “Rangers”),

This is STILL about cap badges and it’s sickening. An opportunity lost. Some of the noises were so encouraging, but the Army really doesn’t seem to have learned, and i think they are damn lucky people are still ready to sign up to it.

Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree more with your comments on heavy armour.

We have world class commando force we should be expanding but are not.

A fully fledged strike division with significant precision long range fires backed up by F35 and Apaches would give any armoured formations run for its money, but it has to be fully resourced.

One thing people are not touching on is if we have another Op Herrick, how the hell will we manage the rotations when everyone will be so thinly spread and not enough mass, perhaps that is the real plan.

Integrating reserves into the main force is also a non starter, as has been discussed in other articles, better to have 4 fully formed reserve BCT’s, North, South, East, West and incentivise command to be able to generate a single BCT at any given point.

LikeLike

Holy cow, preach brother! Biggest problem with Army might not actually be the lack of funding but the lack of imagination at senior levels.

LikeLike

All the nonsense about the future of MBTs that was banned about over the last decade, as finally become official policy. By the way, it’s still nonsense, and to prove it no major World power is considering relegating their MBTs, in fact, many are developing new vehicles to replace current fleets. The MBT is not dead and nothing offers infantry support like a bloody great tank or breaking through obstacles that otherwise would tie down forces. Another fact that has escaped the military planners is the political relevance of an MBT. Being a fellow user allows you a place around the key strategies and not relegated to recon and other support roles. Sadly, I can not see this pecking order changing any time soon.

If you want to take out other MBTs or lighter armour then the CH2 is the kit you need. Boxer, Ajax, won’t protect like a CH2. New survivability technology is broadening the chances of MBTs succeeding, where in the past they would have been vulnerable to many threats. The arguments that Britain is an island and is not so dependant on battle tanks as landlocked nations are also misleading. The UK has used MBTs in countless overseas operations, thus proving that it is an active user of the systems. 148 CH3 is a mistake but the MBT doubters have won the day (so far) however, we will have to see how future crises develop, to see if the policy is either prophetic or foolhardy?

LikeLike

Hi Maurice, good reply. I’m not doubting the protective value of MBTs. But what is undeniable is that we will not have enough to make viable formations, certainly at scale, so if you can’t resource forces properly, you’re doing more harm than good to the troops you put in the firing line. Added to this, no viable IFV is going to be provided for armoured infantry. So, as it stands, British armoured formations will roll into combat in an environment potentially saturated by cheap stand-off anti-tank submunitions carried by UAVs, missiles or lobbed into the scene via long range fires, infantry will be in obsolete vehicles offering little protection, and all this in the hope of closing to get a pop out of a direct fire 120mm main gun. And these will be the only formations we have, there will be no capacity (at 140 odd tanks) to soak up losses. we have no mass. Countries that are serious about armoured warfare are buying large numbers of MBTs, Poland for example, and the Americans still have thousands of MBTs. we (will) have 148.

As for pecking orders, however many MBTs, drones, helicopters or whatever you have, I think your place at the table is going to be determined by what you can do, not simply by what you have, because on that count, Maurice, we don’t have a whole lot to show. So thinking out of the box, looking for new ways to use the forces you do have and optimising their particular skills, might be a more cost effective (and safer) bet than trying lamely to keep some (withered) skin in the game. The fracas in the Caucasus isn’t necessarily representative of how exactly combat scenarios will play out among much more sophisticated forces in a European theatre. But do the math. A CH3 won’t be a penny shy of $10million. Its gun’s effective engagement range will be 1-3km; Spike in the ER and NLOS versions have ranges from 8-20km, cost just over $200k a pop, and in the latter case require no sustained marking of targets. Just a recap: we didn’t get out of the trenches by buying more horses or machine guns, that was tanks, aircraft, artillery and infantry in effective combined arms; now it’s time to think laterally again.

LikeLike

Thank you for your response to my bitch about the loss of MBT clout. Your knowledge on the subject is impressive and I respect that. What I can’t get out of my mind are the images of CH1’s charging across the desert in support of allies during the Desert Storm and the subsequent Iraq conflict, both events occurring in modern times and still within the time envelope of current equipment. Prior to that, the images of WW2 and how impressive the British tanks were in cutting a path to victory in Europe, without which, we would not have won. In terms of basic military practices, not a lot has changed, and another dash across a desert or eastern prairie can’t be ruled out. Any significant military action that may face NATO, there is a strong chance MBTs could play a critical role, and by the end of this decade, the UK will simply not have the tank reserves required to fight a protracted exchange? This will limit what the UK can contribute in terms of a conventional heavy punch, and could relegate it from playing a key role as mentioned above? In short, we simply haven’t technologically moved forward enough to reduce the MBT component from our land forces, and with improved survivability being actively applied to tanks, it still has relevance. The CH3 will be a beast of some repute I have no doubt, but sadly, the numbers are pitifully small and that does a great injustice to those brave tank crews, who went before and those who man them today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“MBT doubters” have not won anything – the treasury has won, again…… this is simply the standard salami slicing cuts of the last 2 or 3 decades. In fact the “MBT doubters” lost the argument that 148 upgraded tanks is a waste of good money that might have been better spent elsewhere. Same argument for 3 E7’s – what exactly is the point? If you can’t afford to fund it properly, as admit and look for alternatives you can afford.

LikeLike

The article I have linked to below is an example of what and how the Command Paper could have communicated in terms of a vision of how the Army fits into the objectives of the Integrated Review. It provides a clear idea of what an Army is for and it’s relevance, and does so without drowning the reader in impenetrable jargon.

https://www.defensenews.com/land/2021/03/29/the-infinite-game-how-the-us-army-plans-to-operate-in-great-power-competition/?utm_source=clavis

LikeLike

I always laugh when the Army top brass say that the Army is “expeditionary”. They must use a completely different definition of expeditionary. There are notionally 8 expeditionary brigades, but that includes the 4 brigades of 1 Div, which would be hard pressed to mount an expedition to the local corner shop to buy a pint of milk. One of the armoured infantry brigades is now in experimentation mode, so that leaves just 2 armoured infantry brigades plus 16 Air Assault. In reality, it’s only really the latter that actually counts, because even the armoured infantry brigades would need some customization to get on the road. Perhaps moving to the BCT format would help, but I don’t understand how modularisation will help if there’s only one of each type of formation. It works for the US Army, because they have buckets loads of brigades to choose from. The US Army has more *types* of BCTs than the British Army has actual brigades (excluding all the non-deployable single arm brigades). A better approach for the British Army, in my opinion, would be modular regiment combat teams, allowing brigade-sized formations to choose from a pick-and-mix of combat, ISTAR, combat support and logisitic RCTs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that the white paper is a mess, and in my opinion the SoS’s speech in parliament was also poor.

I wonder why the paper was so disjointed, what was changed last minute. Was in the structure, certain equipment programs or was it the removal of almost all dates and numbers. I suspect the later. I think the treasury is worried the Covid and the Brexit omnishambels will effect the ability to fund the plan and demanded room to make changes without it causing to much political drama.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A spot-on assessment of the primary objectives that shaped the review. Although I would think that one could be even bolder on the second one: with this IR, the UK has effectively removed itself away from the Continent’s concerns. In some sense I would think that the UK is positioning itself to be able to reach out to Russia, whenever circumstances make it possible, say the leadership there changes. It does make perfect sense from the new British perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have decided to take a watching brief on the review. I really think that there has been a massive amount of cost cutting – which I don’t obviously like nor do any of us. However, it remains to be seen as to whether it is cost cutting with purpose or not. The one decision I really think is a mistake is the purchase of only 3 Wedgetails.

The C-130 could make sense as it’s not suitable for long global deployment missions (although it could relieve pressure from A400m & C-17) as long as rectified in terms of more A400m or a new capability such as KC-390 if (big if) this happens then great. Also greater use of A330 could help.

In terms of land power I think considering the stage WCSP was at I think it’s unfortunate especially considering the firepower lost at least temporarily (hopefully). However, if Boxer replaces in number the effect on deployability of AI could mean a significant reduction in the dependence on HET.

Recent announcements look promising in terms of modernisation, adoption of nano bug UAVs, 40mm grenade launcher LMs now to be armed, Sling shot BLOS Comms, the most exciting development seems to be the modification of MLRS to include mobility via composite rubber tracks & precision fires.

So at the moment I am undecided but it seems that there’s a sober reality on what we can afford to do but ensuring what we do is done well.

Despite losing the Strike Brigades for whatever you think of Strike the concept that led to it, is to me sound. I am more comfortable with Deep Recce Strike concept than deploying infantry mass that to me would get entangled in firefights especially in urban environments.

Gone are the days of massed formations they will simply be decimated by indirect fires. So we need to consider this in how the Army may operate. I don’t agree that less mass is better, but certainly straight numbers may not dictate direct capability.

Criticism of the Rangers I understand but actually if it works out as I think envisioned it could stop the next Afghanistan or Mali.

There’s other rumours of GBAD improvements, Loitering munitions, UGVs etc.

I think it’s a wait & see unfortunately the real judgement will be in 10yrs plus – hopefully that doesn’t prove too late. Only time will tell if the correct decisions have been made …

LikeLike

To UK Land Power

Another first-rate piece. It is lucid, incisive and thankfully, devoid of that ghastly jargon which is creeping into military documents, the main purpose of which I’m convinced is obfuscation.

This blog has the title “UK Land Power” and I therefore intend to concentrate on the parts of the Review and the Defence Command Paper dealing with the Army. The latter paper, as you say, does have a kind of disjointed quality to it, as if it had been subject to very late alterations.

Perhaps one of the most telling comments you make is: “Meanwhile, a failure to manage the acquisition of new armoured vehicle types has reduced confidence in its ability to plan and implement its regeneration needs.” There is that lovely paragraph from Lee Cook (I’m not going to quote the whole thing, because, as you will see, I disagree with some of his views, but it starts:“I don’t know whether to cringe, cry or scream. where are we going? You read one good thing: we’re going to be expeditionary, agile, lethal and light. Then you read …………….. and finishes “and then (just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse), we’re going to replace that scrap with wheeled vehicles…back to unmanageable, incoherent tracked/wheeled formations.” It certainly captures the absurd indecision and confusion accompanying the planning and implementation of new armour.

I disagree strongly with the plan to go without a tracked Infantry Fighting vehicle. You put your finger right on the problem when you say: “if we find ourselves needing to go toe-to-toe with a peer adversary, tanks and tracked IFVs will remain essential. Nothing else provides the level of all-terrain firepower, resilience, persistence and shock effect. Combined arms armoured brigades remain the most expensive unit of land warfare currency, but cost alone should not disqualify them being part of the future force.”

What about the new IFV version of AJAX, which was put on display last year? Is there any more news on its development? Is it likely to be prohibitively expensive? It would seem to me that thee capability will have to be gapped , rather than discarded. Despite all the improvements in tyre technology and traction to wheeled vehicles like Boxer, they are still not really the equal to tracked ones in heavy armoured formations.

I was not going to write until I saw the post from Simon Mugford. In it he talks sensibly about recent announcements not mentioned in the Review, the most exciting of which seems to be the modification/upgrading of GMLRS. He might very well be right when he speculates that other equipment orders might follow. Loitering munitions have already been ordered. There are a lot of gaps still to be filled.

LikeLike

Mike, the Army will definitely acquire a new tracked IFV in due course. But it is unlikely to be based on Ajax. No decision will be taken about Ajax until the current order is successfully delivered. Of course, if GD doesn’t turn this around, there is always the possibility that it could yet be cancelled. In the meantime, a turreted Boxer would certainly make a useful substitute. With a 30×173 mm turret, twin ATGM and APS, it would be a formidable vehicle. While it would lack the off-road mobility to fully replace a tracked IFV, it would offer more utility across more scenarios than an upgraded Warrior. Given the choice between a tracked-IFV and a turreted Boxer, I would definitely go for the latter. France’s VBCI works very effectively with its Leclerc MBT, despite being wheeled. For me, this discussion boils down to Boxer arriving where it is needed in time to deliver an effect – due to units equipped with it being able independently deploy. A tracked IFV battalion forced to wait for tank transporters that never arrive, is useless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How about an article comparing the various tracked IFV options that the Army might consider?

LikeLike

Can you wait a few months? Need OMFV to firm up, as well as Australia’s Land 400 Phase 3 competition and Hungary.

LikeLike

Beggars belief that the Ajax programme has fallen in to the canal, its 30 years old for FFS! What can be so impossible?! It’s beyond a joke! I know our industrial base is dwindling but we still have world class engineering and manufacturing here. Maybe we could get some of those dudes from Nissan or Honda to take over the project?

Funny how companies with a true commercial imperative actually know how to make products that work.

LikeLike

I’d love to know how much of it is down to the vehicle itself and how much is it down to LM not having a clue how to build a turret. If we had have selected BAE with the cv90 would it have all been plain sailing and in service by now or same story all over again.

LikeLike

As regards the actual defence review, as Stalin liked to say, “How many divisions does the Vatican have?”

LikeLike

It seems the UK will struggle to rapidly deploy and sustain 1 armored brigades based on the current proposal. Wouldn’t it make more sense to have 3 armored brigades and have 3 light brigades (based on a structure like the US infantry brigades of 2006)-achieved by adding about 2000 soldiers to the force? That way there would be 2 brigades readily & sustainable available for deployment-the armored for high intensity combat and the light brigade for other theatres. Additionally , the deep rec strike brigade team should be organized into 2 “battlegroups”- since a single unit isn’t readily deployable on a continuous basis and it makes no sense for a recon/screening force to be as big as the unit it is screening for (ie the single armored brigade that can be sustained on deployment). That would also leave the para brigade available as a strategic reserve.

LikeLike

With regard to the deep recce brigade, I would recommend reading Scouts Out! by John J McGrath [1]. This basically concludes that specialized reconnaissance units bigger than company size are a waste of time. Battalion-, regiment- or brigade-sized reconnaissance units are almost never used for actual recon missions, but instead are used as general combat units. Conversely, recon and security missions are almost always undertaken by regular combat units temporarily assigned to that role. This was based on comprehensive analysis of several combat histories from WWII, the Israeli wars of the 50s to 70s, Vietnam, and through to the first Gulf War. Once again, it looks like the British Army is basing doctrine on the units to hand, rather than the other way round – we have all these cavalry regiments without anything to do, so let’s invent a concept called deep reconnaissance that sounds sexy enough to justify keeping two hussar regiments on the books.

[1] https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/combat-studies-institute/csi-books/scouts_out.pdf

LikeLike

Addendum- the light brigades could also have a reserve infantry battalion “attached” so in a high intensity conflict that unit could be mobilized to create a more traditional infantry brigade.

LikeLike

The three papers, IR, Command and DSIS, are together supposed to set a clear future strategy for our armed forces. Taken together, I feel they are a serious failure. The IR, which is at least well written, covers so many potential threats( it is surprising not to see mention of asteroid strikes or alien invasion)that it results in no coherent prioritisation or focus. Instead, as you observe, the dispersal of ever smaller forces in a forward deployed global presence is just using the bases we have now. The Command Paper is much worse, couched in strange and at times meaningless gobbledegook and utterly failing to set out the details of numbers and timescales one might expect. The DSIS has attracted the least attention but may in the end prove to be the most important. It promises a move away from competitive sourcing to regenerate domestic capabilities with a land industrial strategy to mirror the national shipbuilding strategy.

The failure to determine priorities means that the gap between the global ambition and the forces to deliver it has grown even wider.

Long term plans rarely survive the next review or unforeseen crisis so the promises for 2030 or 2035 may never be met. But somethings are more certain because the funding demands them:

The RAF will lose some of its current grossly inadequate combat fleet. Whilst there is a commitment to increase the F35 fleet, there appear to be no plans to buy any other combat aircraft until Tempest arrives in 2035. Is there no plan to replace Typhoons lost to accidents or fatigue or is this a detail yet to be decided? Either way, the RAF has lost half it’s combat power over the last few years.

The RN widely seen as the winner in the reviews, will see a reduction in hull numbers.frigates.minehunters maybe OPVs before numbers start to recover in the early/ mid 2030s. It is unlikely that enough F35s will be bought to make effective use of both carriers.( Some additional improvements have been announced since the reviews on missile upgrades)6

The army seems to be left in a muddle of overlapping force and organisational structures I don’t fully understand. Its equipment plan is in disarray, with Warrior soldiering on unimproved for several years. The numbers of MBTs to be upgraded is too small and the costs at over £8m per vehicle excessive. The costs of other vehicles means they will be too few and acquired over an extended period. A Boxer may be better than the French Griffon but is it 5 times as good?

Summary : the desire to seem global has led to a loss of focus on the most important threats.

There is no resilience in any of the forces with too little in the way of reserves.

There is an almost childlike faith in unmanned systems that are likely to prove just as expensive as their manned equivalents.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see a lot of complaints in the comments above about the lack of a new tracked IFV or some Warrior upgrade. As an outsider, I must ask: what would be the benefit of either of these two moves right now? The British Army has 2 vehicles on order: nearly 600 Ajax and 500 Boxer variants. Essentially none of them are here yet (I’m not counting the small number of Ajax) and according to various reports it may take the whole decade for all of them to arrive. They are simultaneously replacing two “waves” of armoured vehicles, if I understand correctly, one from the 60s and the other from the 70s. So essentially one generation of vehicles has been maintained a bit longer and you now have to combine in one decade what ideally should be done over a longer period of time.

This is already creating an added pressure. Why bring the new tracked IFV to the mix? What would be the added value of trying to replace your whole stock of APCs/IFVs/etc within a short period of time? The vehicle you are buying now will have to last 30-40 years, maybe longer. You would have a brand new fleet for maybe 10 years and then an increasingly obsolete one. And at the end of the cycle you would have to replace the whole set again at the same time. Increasing the costs and adding unnecessary pressure onto the military.

Why not to wait 5 years and see how your new vehicles are going to perform for you? If you like them, what would stop you from increasing your orders by a couple hundred each? And if for some reason you won’t like what Ajax or Boxer provide, wouldn’t this give you a better insight into the procurement of the new type? I just do not understand the rationale behind mounting all the orders in one short period of time.

As for the Warrior upgrade, unless you are planning a war with Germany or France, is it really going to be too obsolete compared to what Russians can field in 2030? Assuming that’s the major ground threat. And even if so (although from what they are saying about Kurganets it is hard to imagine it), would you rather spend your money on the costly upgrade, or on additional purchases of new vehicles?

LikeLike

The problem is that the Warrior and CR2 upgrades have been delayed so long that they are both essentially obsolete in their current form. As you say, Boxer and Ajax are at least a decade away from being fully operational. Does the British Army just hope that it doesn’t have to fight a war in the next 15 years? Some capability needs to be retained until the new force starts to shape up around whatever equipment is left.

I think there should be a short term purchase of a tracked IFV, using something that is already in use elsewhere, like Puma or Lynx KF41. These would fit easily into current doctrine and force structure, so could come into service within a couple of years if treated as a UOR purchase.

LikeLike

The delays in the replacement of old equipment are common throughout Europe. But I am not sure that British Warrior is really obsolete when compared to Russian BMPs. (I’m tacitly assuming that this is the only possible near future peer adversary for UK.) And there is no way to turn it into a viable threat against Russian tanks.

On the other hand, the off-the-shelf Lynx is not that readily available. Hungarians ordered them for 3 battalions last year. The first ones will arrive in 2023. Suppose you order them right now, you’ll get your first battalion around 2025. That’s being optimistic about it, as Hungarians are really the first to test the waters with this IFV. Doesn’t it make more sense to wait and check what happens to Ajax? Because if its issues can be resolved, then it can also serve as a viable tracked IFV. Commonality has benefits. Especially if the order will be for at most 300-400 vehicles.

And if the Ajax doesn’t work, then the Brits really could use a complete solution. Buying the Lynx or Puma beforehand may prevent that.

LikeLike

For 80% of potential future deployments, Boxer will be more than good enough in an IFV role, if a turreted version is acquired and this has at least a 30×173 mm cannon, twin ATGM and APS. It will totally make the Army more deployable across more scenarios than Warrior. The real issue is what happens if we need to deploy to the Baltic States in mid-winter when the whole area is covered in snow? For some geographies, a tracked platform would be preferable. So having two Boxer brigades plus a an equivalent tracked brigade in Ares for extreme terrain deployments would be good. The most unimaginative part of the Army’s IR submission was not grouping Boxer and Ajax in separate wheeled and tracked brigades.

This brings us back to Ajax. I repeat what I said elsewhere. This could form the basis of a new IFV, but first we have to get the basic reconnaissance family right first. And we still seem some way away from doing this. If GD isn’t stepping-up to make it happen, then we need to re-think the programme. Delivery was originally scheduled for 2016. it is now five years late. They’re now talking about 2023 for IOC.

LikeLike

The second paragraph makes one really think and ask if it is time to make any decisions regarding the tracked IFV before figuring out what will happen with the Ajax?

LikeLike

How about an article comparing the various tracked IFV options that the Army might consider?

LikeLike

Some comments on the SDR now I’m not feeling quite so ranty…

1. Any reduction in front line airpower is ludicrous. Just ask the Israelis.

2. Whatever its force structure the Army needs a massive recapitalisation programme costing billions. That’s a tough sell given the long and expensive litany of failed procurement programmes over seen by the Army and MOD, but it can’t be avoided.

3. Our single carrier battle group isn’t going to intimidate the Chinese one bit. Let’s not pretend otherwise. Assuming that the Suez canal happens to be open at the time, by the time the Royal Navy get to the Indian ocean the fight will be over. The Chinese have invested massively in hypersonic and ballistic ASMs to create an access denial capability that already pushes a USN CBG out beyond the operational radius of an F35. Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Australia, Thailand, Singapore and even the Philippines are busy rearming with US support. They are in the neighbourhood and don’t need our “help”. It would be Task Force Z all over again. I doubt our CBG would survive a single saturation attack. We’re kidding ourselves. Our carriers don’t even have a single SAM.

4. If we aim to increase our security against the Chinese it might make more sense if we prevented them from building our nuclear power stations or telecoms networks. Call me old fashioned.

5. A battalion of Royal Marines in the Indian Ocean is just big enough to get itself in trouble and need rescuing by the Americans.