By Nicholas Drummond

Contents

01 – The need for an Expeditionary Capability

02 – Stryker: a new type of vehicle, a new type of formation

03 – 8×8 becomes a universal standard

04 – Rebalancing the “Iron Triangle”

05 – Utility across low, medium and high intensity scenarios

06 – Emerging Medium Weight doctrine

07 – Summary

01 – The need for an Expeditionary Capability

At the height of the Cold War, the British Army had four complete armoured divisions, with some 1,200 MBTs, supported by an artillery division, sitting in Germany, waiting for an attack that fortunately never came.

The forward basing of troops made sense. Chieftain and Challenger MBTs weighed 60-70 tonnes, so transporting them from the UK in a time of crisis would have been problematic. With most of our BAOR armoured vehicles located within 50 kilometres of their deployment areas, a rapid response to an attack could be ensured. It was a logical strategy when the major threat was that posed by Warsaw Pact forces.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, Western governments began to talk about a “Peace Dividend.” It meant that they no longer had to commit massive resources to Defence. NATO members started to bring their armies home from Germany or simply to reduce them in size. Ironically, no sooner had the Cold War ended, than it became necessary to deploy the tanks and armoured personnel carriers that had remained largely unused for 50 years.

The First Gulf War in 1990-1991, required a large force to be transported to the Middle East. The logistical nightmare of transporting thousands of vehicles thousands of miles meant that it took months to build-up sufficient numbers of MBTs and IFVs vehicles to evict Saddam Hussein’s forces from Kuwait. It was a scenario that was repeated in 1999, when the US Army attempted to deploy Task Force Hawk from bases in Germany to Kosovo. On this occasion, by the time its Abrams M1 MBTs and Bradley M2 IFVs arrived in theatre, the conflict had been resolved.

Following the Kosovo fiasco, the US Army returned its armoured units to Germany. Senior commanders began to question the utility of heavy armour. Further investment ceased and NATO’s fleets of tanks and personnel carriers were left to “rust in peace.” Many of those that remain in service today date back to the early 1980s or before.

In 1999, the incoming US Army Chief of Staff, General Eric Shinseki, was tasked with modernising the US Army. Referring to the prevailing mix of heavy and light armour, he said: “The US Army is either too fat to fly or too light to fight.” As he set about developing his Objective Force concept, that would bridge the gap between heavy and light forces, he began to think about the Army’s future AFV requirements. A clue was found in the US Marine Corps’ successful adoption of the LAV-25 amphibious reconnaissance vehicle. Dating back to the early 1980s, this platform was the first modern 8×8 and the first to be used in combat. It had performed well in Panama and during the First Gulf War demonstrating exceptional responsiveness and agility. As such, it provided an ideal blueprint for a new expeditionary capability.

02 – Stryker: a new type of vehicle, a new type of formation

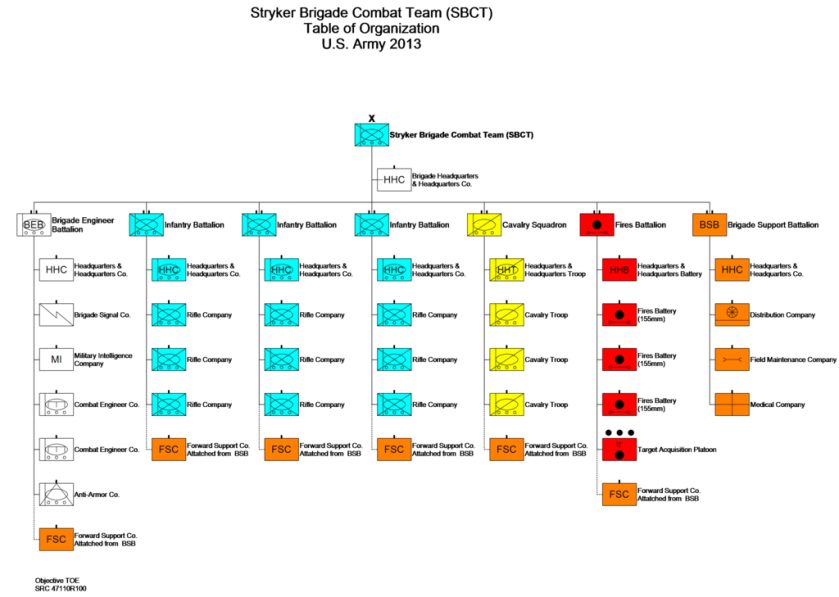

The US Army began to define and develop what it described as a new “Medium Weight” concept that would be rapidly deployable by air or land. This became the basis of a new type of brigade, the Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT). Instead of replacing M113 APCs with a new tracked vehicle, a wheeled 8×8 platform was acquired instead. This was based on an improved version of the MOWAG / General Dynamics LAV platform, the LAV III. This weighed under 20 tonnes, so that it was air transportable in a Lockheed Hercules C-130. The goal was to be able to transport an entire brigade anywhere in the world within 96 hours.

The baseline personnel carrier became the foundation for an entire family of vehicles, including an Infantry Carrier Vehicle (ICV); a Mobile Gun System (MGS) mounting a 105mm tank gun; a 120mm Mortar Vehicle; a TOW Anti-tank Vehicle; a Reconnaissance Vehicle; a Command Vehicle; a Repair and Recovery vehicle; an Ambulance; and many other variants besides.

The first Stryker Brigade was deployed to Iraq at the end of 2003. Travelling by sea, it docked in Kuwait before moving 700 miles by road to Northern Iraq. Its mission was to relieve the 101st Airborne Division, which was primarily equipped with the lightly protected HMMWV. The SBCT moved as a single entity, in a single bound. Though it moved by road, the off-road mobility of the 8×8 platform was such that it could go almost anywhere it was needed. What was different about the formation is that the logistics tail, which usually follows behind such a large formation, was absent. The SBCT was independent and self-contained.

En route to its intended area of responsibility, the SBCT was re-tasked to provide support to a non-Stryker unit overwhelmed by insurgent activity. The SBCT was able to act decisively and quickly to avert a potential disaster. The reach, speed of response and concentration of force it was able to muster were force multipliers. The mission was accomplished with surprising speed, enabling the SBCT to move to its originally intended deployment area. In relieving a much larger force of light role infantry, Stryker Brigade units discovered that their increased agility, lethality, and survivability enabled them to dominate a larger area with fewer troops.

Something else was different about the SBCT. It was fully networked with an advanced Battlefield Management System (BMS). The timely sharing of real-time data across units, from top-level command down to low-level units, allowed a very accurate picture of a situation to be quickly established. Command and control became easier and the tempo of operations became faster.

Something else was different about the SBCT. It was fully networked with an advanced Battlefield Management System (BMS). The timely sharing of real-time data across units, from top-level command down to low-level units, allowed a very accurate picture of a situation to be quickly established. Command and control became easier and the tempo of operations became faster.

The M1126 Stryker vehicle offered much greater protection than a HMMWV jeep, but was not perfect. As a result of its first deployment, the vehicle was up-armoured by giving it a double-V hull (DVH) and composite armour to counter rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). What was clear, however, is that the Stryker concept was revolutionary.

03 – 8×8 becomes a universal standard

By 2007, the Polish Army deployed to Afghanistan with its own 8×8 Medium Weight vehicle, the Patria AMV. Instead of mounting a 12.7mm heavy machine gun, this had a 30mm Bushmaster cannon in an OTO-Melara turret. This transformed the vehicle into an extremely capable IFV.

AMV units were not invulnerable, but protection levels were much higher than legacy light armoured vehicles. The Polish Army experienced 300 separate IED attacks against AMV vehicles. Of these, 21 resulted in vehicles being rendered immobile, through the loss of wheel stations, but only 8 vehicles were damaged beyond economic repair. Although some soldiers were seriously injured, there was only one fatality.

The German Bundeswehr fielded the ARTEC Boxer in 2011. With a highest level of protection yet seen in an 8×8, there were no German fatalities with Boxer in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, the French Armée de Terre acquired the Nexter VBCI. This too was well protected, but additionally mounted a 25mm cannon. The French intervention in Mali in 2013 was considered to be a textbook expeditionary operation with wheeled units deploying over thousands of kilometres to achieve their tactical objectives.

By 2014, the 8×8 platform had firmly established a new category of AFV. Gross vehicle weight had grown from under 20 tonnes to 32 tonnes and most offered at least NATO Stanag 4569 Level 4 blast and kinetic protection. Although newer 8×8 vehicle types were too heavy to be airlifted by C-130, the Airbus A400M has a 40-tonne payload allowing all current 8×8 types to be carried.

04 – Rebalancing the “Iron Triangle”

In analysing the impact of medium weight formations, they have rebalanced the iron triangle of lethality, survivability and mobility to place much greater emphasis on mobility. Or, as some US Stryker Brigade aficionados would say: “mobility is protection.” In a wider sense, the iron triangle has expanded to encompass six vital AFV attributes:

- Mobility

- Survivability

- Lethality

- Adaptability

- Logistical footprint

- Connectivity

Mobility now consists of three elements: strategic mobility – how a vehicle gets from its country of origin to the theatre of operations; operational mobility – how a vehicle gets from the theatre entry point to the area of combat operations; and tactical mobility – how a vehicle moves around the battlefield.

Adaptability is being able to use a vehicle for different mission types with minimal reconfiguration. Logistical footprint is concerned with reducing logistical dependancy and the ability to conduct longer (72-hour) missions. It about lower vehicle acquisition and operating costs, including reduced training and maintenance requirements. Connectivity is the digital backbone of a vehicle that supports networked C4I systems to allow effective communication and the exchange of data between vehicles.

Every army in NATO has now adopted a medium weight 8×8 vehicle, with one notable exception: the United Kingdom. The saga of FFLAV, MRAV, and FRES UV is well documented elsewhere, but reflects several failed attempts to identify and procure a suitable 8×8 candidate. The ARTEC Boxer, Nexter VBCI and General Dynamics Piranha 5 were evaluated. While any one of these vehicles would have been suitable, none was selected. A new programme, Mechanised Infantry Vehicle (MIV) has now been initiated. It is anticipated that the UK will finally field a medium weight capability from 2021.

Among the armies that have adopted 8×8 vehicles, a large number of variants have emerged:

- Infantry Carrier Vehicle (ICV)

- Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV)

- Command & Control Vehicle (C2)

- Direct Fire Support (DF)

- Reconnaissance (RECON)

- Antitank (AT)

- Mortar (MOR)

- Battlefield Ambulance (AMB)

- Repair & Recovery Vehicle (RR)

- Air Defence Platform (AD)

- Artillery Platform (SPG)

- Engineer Vehicle (ENG)

- Bridging Platform (BR)

- Chemical Biological Radiological & Nuclear Defence (CBRN)

Equally important, potential adversaries have also acquired a medium weight capability. In fact, Russia and China have used 8×8 BTR-60s and BTR-70s as part of Motor Rifle Divisions since the 1960s. Both have now invested in modern 8×8 platforms.

With Western armies primarily involved in low-intensity and counter-insurgency campaigns against relatively unsophisticated enemies, the focus of protection has been countering the effects of mines and Improvised Explosive Devices (IED). With higher centres of gravity and V-hulls, wheeled vehicles tend resist them better than legacy tracked vehicles that have flat-bottom hulls.

In the 1950s when the first tracked APCs were conceived, such vehicles were described as “Battlefield taxis” that would deliver the dismounted soldier ready to fight. The evolution of the APC into the IFV saw such vehicles enable soldiers to fight mounted as well as dismounted. Modern 8x8s confer the same benefits, but in addition they are also “Mother ships” that support the infantry they transport by carrying their equipment, charging their batteries, and resupplying them with spare ammunition, water and rations.

Perhaps the most under-rated attribute of 8×8 armoured vehicles is simplicity. Versus an equivalent tracked vehicle, they reduce costs by 40-50% while offering the same level of utility. They are easier to operate, simplifying training and combat. They allows more vehicles to be acquired for a given cost. This matters because experience has taught us that “quantity has a quality all of its own.”

05 – Utility across low, medium and high intensity scenarios

By 2014, the Cold War was a distant memory. Low and medium intensity conflicts were considered to be the most likely scenarios. Da’esh was undefeated in Iraq. Boku Haraam was active and growing in power in Africa. Syria and the Yemen were hotbeds of extremist terrorist activities. Recognising that counter-insurgency campaigns take time to win, we quietly developed the necessary resources to achieve our political and military goals. Medium weight forces were ideal in this respect.

Then Russia annexed the Crimea. NATO was not able to react quickly enough to deploy forces that might have deterred Russian aggression. There are now concerns that Vladimir Putin has his eyes on the Baltic States. Not surprisingly, the situation has created a new stand-off, forcing NATO to deploy a multinational brigade to Estonia. In the face of massive Russian forces, this brigade has been described as a “tethered goat.” NATO needs to be able to deploy forces in case the threat intensifies. If the Baltic States were attacked, it would more than likely trigger a nuclear exchange. Medium weight brigades are seen as the perfect antidote. The US Army is beefing-up its Stryker Brigades in Europe by adding a cavalry regiment equipped the Stryker Dragoon, which mounts a 30 mm cannon. Such brigades can deploy rapidly as the situation demands. If necessary, they can hold ground until heavier armour arrives.

In Asia, North Korea has escalated tensions with the USA by actively embarking on a nuclear missile programme. Iran has emerged as a major sponsor of terrorism. It has become clear that the threat of nuclear weapons acts as a powerful Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) strategy that prevents a response after an act of aggression. While the situation the Ukraine and the Baltic States suggests that heavy armour still has a role to play, the need for agile forces capable of divisional level manoeuvre at distance to pre-emptively counter such threats has been brought sharply into focus. But the truth is we’re not very good at predicting future conflicts. We invariably are equipped for the last war not the next one. This suggests that we need a mix of forces: light medium and heavy, capable of operating across a wide spectrum of threats. Medium weight formations excel at providing a highly flexible, general purpose capability.

In addition to being able to move rapidly on tarmac roads and tracks, 8×8 vehicles also offer a level of off-road performance that matches that of a tracked vehicle. Ultimately, tracked vehicles will retain an edge in sand, snow and very soft soil conditions, but, most of the time, a combination of on-road speed, off-road agility, and vehicle reliability, means that 8×8 formations can operate independently over considerable distances. This is a new and game-changing capability. Groups of vehicles can advance or withdraw in small packets or larger convoys, as the situation dictates. They can infiltrate tactically via different routes. They can concentrate or disperse at will. They can easily be integrated with heavy or light forces. They offer tactical flexibility across a wide range of mission types. This concept of employment is often referred to as integrated action and, when successfully implemented, fully reflects the aspiration that medium weight forces should be adaptable and responsive.

06 – Emerging Medium Weight doctrine

At its heart, medium weight doctrine reflects a fundamental shift in doctrinal thinking. First and foremost, it is about having a rapidly deployable expeditionary capability that allows infantry mass to be deployed independently at distance. It recognises that, in future conflicts, getting to the fight is likely to be as challenging as the fight itself.

The second key aspect of medium weight forces is that they are a key enabler of divisional manoeuvre. This means that they provide an Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) component; an independent strike or raiding capability; a screening force operating ahead or protecting the flanks of a division; and enabling heavier units to move unimpeded out of contact.

Using medium weight forces effectively is about information manoeuvre. This is moving pre-emptively, somewhat like moving a chess piece defensively, to counter a corresponding enemy threat or movement. Medium weight forces can rapidly to encircle, seize and hold territory. They also allow infantry to dominate ground through aggressive patrolling, mobile ambushes and rapid reinforcement.

The most significant shift in thinking is that medium weight vehicles are not intended to take-on main battle tanks. Ideally, these will be defeated by combat aircraft, attack helicopters, long range ATGMs and precision fires. Medium weight formations will avoid or outmanoeuvre a superior enemy force through the speed and agility of their wheeled vehicles. Connectivity also plays a part in this. When medium weight units are networked into other C4ISR assets, this builds a real-time awareness of enemy dispositions. Allocating dedicated UAV support will provide a timely warning of any enemy forces heading towards it, but also the ability to neutralise enemy armour.

Another critical aspect of modern land warfare is air power, which has become a turnkey asset. With air superiority, ground forces can manoeuvre almost unimpeded. Without it, AFVs of all types are extremely vulnerable. The most likely scenario is air parity, therefore ground forces will need to be agile and discrete. Slow moving tracked vehicles with conspicuous signatures will be easily targeted, especially when operating in concentrated groups.

Medium weight vehicles, operating in both small and large formations, will encounter other medium weight forces and, inevitably, enemy tanks and heavy armour. Thus, they will need to be able to defend themselves by engaging and defeating these threats with direct fire weapons, such as 30-40 mm cannons or ATGMs, from under armour. Bradley M2 IFVs equipped with a 25mm cannon and twin TOW missile launchers successfully countered Iraqi tank units with T-72 tanks during the first Gulf War.

Some armies, including Italy and Japan, who have large coastlines to protect, have opted to develop 8×8 tank destroyers. Designed to respond quickly to repel amphibious landings, they mount 105mm or 120mm tank guns that fire a mix of ammunition types. Large mobile gun platforms may look like wheeled tanks, but, with lower levels of protection, they are vulnerable to MBTs. Consequently, they must achieve first-round hits or risk annihilation. Given that 8×8 vehicles with large guns have the same reduced level of protection as other 8×8 platforms, a 105mm or 120mm smoothbore gun is a benefit more than a hindrance. It remains to be seen whether wheeled tank destroyers will define a new sub-category of 8×8 vehicle.

Attack helicopters firing long-range ATGMs beyond the range and elevation of tank guns may be more effective tank destroyers. Vertical lift will certainly play a key role in supporting ground forces, as will close air support (CAS) delivered by fast jets. However, a mix of miniature UAVs used to guide long-range ATGMs, may be less costly, but equally effective. It should also be noted that tracked vehicles tend to provide more stable platforms for large guns.

While medium weight formations will need to have potent organic firepower to defeat other AFVs, they are themselves vulnerable to cannon and ATGM fire. The advent of Active Protection Systems (APS) is a welcome innovation that will increase their survivability against HEAT warheads. Even so, 8x8s still only have limited protection and will need to be used with discretion to avoid unnecessary casualties.

07 – Summary

Future operating environments are likely to be characterised by urban, littoral, and other complex terrains. In complex, congested and contested future battle spaces, large scale tank battles are unlikely to be the norm. Combat ranges will be shorter, often less than a kilometre, with all vehicles at risk to enemies operating handheld ATGMS from the rubble of ruined buildings. Dominating towns and cities will require large numbers of infantry to be used. The timely deployment of dismounted troops is likely to be the difference between success and failure. The most essential attribute of a medium weight capability is therefore protected mobility that delivers dismounted infantry to wherever they are needed on the battlefield. In this sense, the 8×8 platform gives infantry a true “go anywhere, do anything capability.”

Despite the many benefits they offer, it should be noted that medium weight forces are not a universal panacea. They can perform many roles, but not every role. When it becomes necessary to mount a direct head-on assault against a dug-in enemy, or to resist a determined attack, heavy armour may still be the best option; in other words, rumours of the tank’s death may be greatly exaggerated. With high intensity conflicts now seen as being more probable, but also more serious than low and medium intensity ones, the question is whether medium weight forces are sufficiently capable to respond to a peer enemy equipped with tanks and IFVs? They may need further development, including the ability to mount larger guns or new hypersonic anti-tank missiles , especially if they are to defeat APS-equipped MBTs and IFVs.

Ultimately, information manoeuvre can be summarised by the adage: “He who gets there first with the most amount of troops, wins.” (Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate Cavalry Commander during the American Civil War when asked to what he attributed his success.) A medium weight force that deploys a brigade to occupy and defend essential territory, that then digs-in with ATGWs, artillery, combat air and UAVs in support, will be be very hard to shift. In modern warfare, it is being there that counts and a medium weight capabilitiy facilitates this very well.

_______________________________

Notes / Sources:

- LAV-25: The US Marine Corps’ Light Armored Vehicle, by James D’Angina, Osprey Publishing, 2011

- General Dynamics Land Systems

- From Transformation to Combat, The First Stryker Brigade at War, by Mark J Reardon & Jeffrey A Charlston, Center of Military History, US Army, 2007

- Future Operating Environment 35, UK MoD, First Edition, 2015

- French Army Operation Serval, Post-Operations Debrief, IAV XV 2015

- Shrivenham Close Combat Symposium 2015, British Army Presentation on Future Capability

Excellent article.

I’d like to understand something though: You state “…medium weight vehicles are not intended to take-on main battle tanks. These will be defeated by combat aircraft, attack helicopters, long range ATGMs and precision fires”. Surely the logistics tail of the first two make an MBT formation look positively light weight? Also can you provide an example of the last two that would realistically be available.

I think there is a bit of a Catch22 with the doctrine. Not for small skirmishes I hasten to add, but for actual war.

I feel as though one is always going to need the MBT because ultimately it becomes a game of being able to defeat enemy armour at a range whereby they cannot defeat yours. The classic boxer’s standoff.

LikeLike

The point to emphasise is that if you deliberately set a Medium Weight formation against an equivalent Heavy Armour one, the former will struggle. In the UK’s case combat air might come from carrier-based F-35Bs, UAVs or allied assets operating locally, e.g. German Tiger attack helicopters. Precision fires would include GMLRS and Exactor (Spike NLOS).

LikeLike

Agree with Simon that it is an excellent article. Knowledgeable and lucid.

You say at one point that “By 2014, the 8×8 platform had firmly established a new category of AFV. Gross vehicle weight had grown from under 20 tonnes to 32 tonnes and most offered at least NATO Stanag 4569 Level 4 blast and kinetic protection.”

Now I cannot remember exactly how long ago it was that the rather pretentiously termed “Trials of Truth” were carried out on three vehicles by the British Army. They were, as far as I remember: the Boxer, the Piranha V and the Nexter VBCI. No vehicle was chosen to enter service, though.

What I wanted to ask was whether the failure to put a vehicle in service at that point proved to be a kind of blessing in disguise. Have we benefited from not selecting a vehicle then because over the last few years 8 x 8s have improved considerably in several directions? Do we now have an advantage from skipping a generation?

Or should we, in future, follow a policy of not dilly-dallying and shilly-shallowing and simply get something into service with reasonable speed? See the FRES fiasco!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The UK “Trials of Truth” were conducted in 2007. The Germans added extra armour to Boxer and fielded it virtually unchanged. Nexter made a few minor modifications to the VBCI based on UK feedback and fielded it, again virtually unchanged. And the Piranha 5 we selected didn’t actually exist at the time. All three vehicles have now been bought by other armies and proved to be excellent. We could have bought any one of the trinity a decade ago – yes, 10 long years ago – and it would have been a great choice. Over that time, the Category has improved but the gains are marginal since the Trials of Truth. We should have bought something, anything, and made it work. I find it extraordinary that Britain has spent almost 20 years trying to buy an 8×8 wagon. Our allies must look at us and think we’re crazy.

LikeLike

Great article indeed. To nit pick I would say the Stryker brigade might have been revolutionary to the US Army., but not beyond in the wider world where the Soviets / Warsaw Pact had relied on 8×8 BTR series vehicles for large motorized rifle formations for decades. As to doctrine, I think we have to acknowledge that we may not have air superiority in a peer or near peer conflict, so any 8×8 Medium formation needs an AA version. The enemy maybe able to deny airspace to our Brimstone armed Apaches and Typhoons, however an 8×8 with a 120mm auto-mortar and a guided top attack munition like the Strix, a long range missile like the Spike NLOS / Exactor and even the US Army multirole missle launcher with 12 Brimstone all provide plenty of options, as would 155mm delivered top attack sub-munition.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The reason i like 8×8s is due to the number of roles they fill and the the number of variants that already exist on a number of platforms.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we ought define what we want medium forces to be. Do we want them to be lighter version of armoured infantry or heavier version of light infantry. Has anyone thought it from this angle? To me it seems what people want is the first. They want to put 120mm gun on a 8×8, medium caliber gun on a 8×8, AA system and the list goes on. This option is also much more expencive but gives greater combat ability. Lets look at german Jäger troops, normally dismounted infantry that fights dismounted in forests and cities but has incredibly expencive battle taxi. This is probably the worst use for modern and capable 8×8 since the vehicle itself isn’t the source of the fighting power but the infantry inside. If we wanted to have heavier version of light infantry we’d emphasise dismounted strenght and indirect firepower. This would also mean that we could use less protected and overall cheaper vehicles, the basic battle taxi concept that is. If we want light version of armoured infantry much more emphasis needs to be placed on the vehicle itself and its weapon systems.

Maybe a middle ground can be found. Medium wheeled brigade of two battalions of heavier light infantry and one battalion of lighter armoured infantry.

LikeLike

he Soviet Union collapsed in 1991

LikeLike

the genesis of medium weight wheeled force UK is the standoff at pristina airport between btr-80 equipped russian motorized infantry (est 30 armoured vehicles) and NATO KFOR!

the british 4th Armoured Bde was supposed to be in charge of the area, but only a reccon troop was on the ground to race the russians for the airport, the chally’s and warriors were still on transporter trailers.

the actual story is that serbian war criminals escaped thru pristina airport, because NATO could not get there first, and that is the reason russia tookover the airport, to let their friends escape!

and that is why wesley clark was so furious,

and all the shit about the british disobeying clark prevented ww3 is SHIT! Upon the british arrival on the road to the airport the russians immediately pointed their guns at them, and the british cowered!

LikeLike

Hi there! Quick question that’s entirely off topic. Do you know

how to make your site mobile friendly? My website looks weird when browsing

from my iphone. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to resolve this problem.

If you have any recommendations, please share.

Thank you!

LikeLike