By Nicholas Drummond

British Army modernisation has become an urgent priority, not only because existing systems have long since reached the end of their intended lifecycles, but also because the Army needs to counter new threats. Given that many new equipment programmes have been delayed by ongoing austerity, are initiatives conceived more than a decade ago still relevant? If not, how should they evolve so that Army has what it needs to be an effective deterrent force? This article looks at the Army’s acquisition record and makes suggestions about how current programmes could and should be tweaked.

Introduction

When it comes to procurement, the British Army is often accused of spending its money badly. This is strange because it genuinely has excellent personnel responsible for the acquisition of new kit and they are supported by equally competent MoD civil servants.

So, the first question to ask is does the Army actually do such a bad job?

A long history of getting it right

Over the years, the British Army has fielded some pretty impressive equipment types. The Centurion tank was arguably the best MBT in the world from 1945 until Challenger, Leopard 2 and Abrams came along in 1979. In the 1950s, Saracen and Saladin gave us a useful medium weight capability long before the concept was ever a thing. The CVR(T) family that replaced them in the 1970s was highly innovative and achieved great export success. We adopted the 30mm RARDEN cannon when everyone else was still using 20mm or 25mm.The FV432 APC has been the Army’s most successful postwar AFV, so much so that it remains in service almost 60 years after first being developed. The 105 mm Light Gun is another success story that continues to this day. When AS90 came into service in 1992, it was described as one of the most capable self-propelled howitzers in NATO. Although Challenger I was gifted to the Army through the demise of the last Shah of Iran (who paid for its development) the evolution to Challenger 2 again gave us a world-beating MBT.

Despite these pinnacles of success, the Army has had its fair share of failures. The SA80 rifle saga is perhaps the best example of how not to procure something. Development started in 1976, but no weapon was fielded for another decade. It failed dismally during Gulf War 1 and didn’t work properly until 2001. More recently, the Bowman communication system arrived 10 years late and was obsolete by the time it entered service. Troops in Afghanistan complained that it lacked range, while it was bulky, heavy and difficult to integrate into vehicles. Most recently, the Watchkeeper UAS has also taken a decade to bring it into service and doubts remain about its fitness for purpose.

The most glaring recent acquisition failure has been our attempt to field a medium weight multi-role vehicle family. This started life as the FFLAV and TRACER programmes in the late 1990s. Then we joined the MRAV programme with France and Germany, which resulted in Boxer. Britain and France left MRAV in 2002. While France successfully pursued VBCI, we moved-on to FRES UV and SV. By the time we selected Piranha V, we couldn’t agree on IP ownership and had run out of money due to the global financial crisis in 2008. It was a disaster that reflected badly on all involved.

In 2008, Sir Bernard Gray, who later became the head of the Ministry of Defence’s procurement agency, Defence Equipment & Support, was asked to produce a report on UK Defence Acquisition. His conclusion was that a set of incentives operating at the centre of the Ministry of Defence caused people to over-programme, which is ordering more capability than the budget can sustain and to systematically under-estimate the cost of those capabilities. Adding to this problem, scarce resources invariably forced the three armed services compete with each other rather than co-operate.[1]

Part of the problem was profligacy, an insatiable appetite for the new, new thing. The desire to achieve competitive advantage through technology caused us to over-reach. Having an anti-tank missile that is world class is one thing, but like the USAF in the 1980s, we do not need and cannot afford to fit $500 lightweight ashtrays to combat aircraft.

We also have a record for mis-managing equipment in service, which results in waste and inefficiency. The Army has just upgraded the SA80 rifle again. The new L85A3 standard includes fitting a new handguard with a continuous rail system, attaching a stud to prevent over-rotation of the change lever, and applying a new surface coating. The cost per rifle is £1,700, which more than the cost for a new assault rifle made by the same supplier, Heckler & Koch.[2]

An overheated budget is also attributable to the rising costs of defence technology, with successive generations of capability types costing considerably more than their predecessors. Further to this, we must not overlook the Government’s own role in skyrocketing costs. In a bid reduce annual costs, it frequently delays or slows down the acquisition process. Delays in granting approval for the Royal Navy’s new aircraft carriers added at least £2 billion to the cost of the programme. When delay the entry into service of new equipment, you not only increase the total cost of whatever it is you are buying, you also have the ongoing cost of supporting the equipment it is meant to replace.

Despite occasional glitches, over its long history, the British Army has tended to get equipment acquisition right more times than it has got it wrong. It is only since 1990, when the Cold War ended and defence became a lower budget priority, that problems have begun to surface. Nearly all of the acquisition-related issues that the Army faces are related to money, or rather the lack of it at a time when it needs to modernise.

Attempting to modernise while fighting two separate conflicts during a global financial crisis causes things to unravel

The need to enhance the capabilities of Challenger 2 and Warrior; to replace CVR(T) and FV432; and to acquire a new family of medium weight wheeled armoured vehicles had been identified as far back as 1998. As the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan intensified, modernisation efforts assumed a lower priority.

Needing to respond to the IED threat, the UK hurriedly procured all manner of MRAP platforms to provide protected mobility. Described as “Urgent Operational Requirements,” resources were thrown at the problem to resolve it quickly. Unfortunately, this took money away from subsequent modernisation initiatives. Making matters worse, many of the MRAP vehicles that were acquired had little utility beyond the campaigns for which they were bought. The Mastiff PMV, for example, has a very limited cross-country performance. Even so, one notable MRAP success was the development of Foxhound. No other vehicle in its 7.5 tonne weight class offers better protection. It was developed within 18 months and, despite teething troubles, has evolved into a highly valued vehicle. It seems strange that, just we have got Foxhound to work perfectly, it will now be replaced by the US JLTV.

Since 2006, modernisation efforts have advanced at a glacial pace. If they had been delivered by 2016, as was originally envisaged, then the Army would be in great shape. When David Cameron’s Coalition Government came to power in 2010, the Army’s need for new kit was acute, but not as pressing as the need to cut the budget deficit. Defence was marked-out for swingeing cuts, so personnel numbers were reduced and new equipment purchases were pushed as far to the right as possible. Any tendency to over-programme was rooted out leaf and branch. All unfunded commitments were discarded. Ruthless cost-cutting and cost-controls dramatically changed the acquisition mindset of all three services.

Since 2010, whatever the Army asked for, it was told it couldn’t have it. For the author, a Defence Industry insider, the most shocking aspect of austerity was Phillip Hammond and Michael Fallon talking about the £168 billion Defence Equipment Plan without any cash actually being released to fund purchase of the things the Government had already agreed the Army could have.

The impact of ongoing austerity

For more than a decade, the Army has been drip-fed cash that has only satisfied its most pressing needs. The Government was happy not to spend on recruitment, for example, because this reduced the overall headcount bill. Any development problems associated with vehicle programmes immediately resulted in “reliability growth trials” that further delayed the award of a production contract, although in some cases this was entirely justified. But, it wasn’t motivated by reducing risk; it was about saving money. We often talk about capability holidays, but, according to one senior officer, the years since 2010 have been like the entire British Army being placed in suspended animation.

The net of all this is that many of the equipment modernisation plans envisioned before we became embroiled in Iraq and Afghanistan have now been overtaken by events. In particular, Russia’s annexation of Ukraine territory in 2014 means that high-intensity warfare versus peer adversaries is now back on the agenda.

As the Treasury begins to release money to deliver longstanding programmes, there is the risk that their scope may no longer be relevant to the threats we now face. General Sir David Richards’ vision when he became CGS in 2009 was an Army built around counter-insurgency warfare. General Sir Nick Carter’s plan for medium weight Strike Brigades became the centrepiece of British Army modernisation. Now, General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith finds himself in a position of having to re-prioritise Armoured Infantry brigades.

The implication is that making good on procurement promises developed before 2010 could now be a mistake. Exceptionally long lead times could now result in the Army getting equipment it no longer needs, while not getting what is really required to execute a new and evolved mission set.

Against this background, the Army has become sensitive to accusations of profligacy, inefficiency and criticisms of its future strategy. The long journey to MIV was ambitious, but was it unrealistic? No. The US Army had reached the same conclusion about future armoured vehicle requirements and its own modernisation efforts resulted in the creation of Stryker Brigades and the M1126 Stryker family of vehicles. These have been hugely successful and have defined a blueprint for other NATO armies (as well as China) who have all invested in an equivalent capability.

What has happened is that the lack of resources and political oversight over all acquisition programmes have hamstrung the Army’s ability to think big. It is terrified of changing a requirement or reducing the scope of one programme to fund a more relevant new one, or to admit that its needs have evolved, lest it be accused of mis-management or incompetence. It certainly doesn’t want to lose money allocated to modernisation.

The climate of austerity has given birth to a further problem that impacts the Army’s ability to make appropriate acquisition choices: how do you fulfil all your equipment needs when you don’t have enough money?

You compromise on what you buy.

This is why we are still operating FV432 six decades after it entered service.

This is why the original Challenger 2 LEP never included a switch to the 120 mm smoothbore gun.

This is why we will only have 148 MBTs instead of the 227-250 we need.

This is why we have decided to upgrade Warrior when most of our NATO allies are buying new IFVs.

This is why we decided to tack-on an order for the US Army’s JLTV, rather than developing our own multirole utility vehicle to replace Panther.

Another by-product of austerity is that we have lost the ability to design, develop and build armoured vehicles in the UK. Instead, we have committed ourselves to a policy of buying off-the-shelf from abroad.

Increasingly, we are buying from a single supplier instead of competing it. This is a problem that afflicts all three services, rather than just the Army. Here are a few examples:

- Boeing AH64 Apache E Attack Helicopter

- Oshkosh JLTV (Multi-Role Vehicle – Protected)

- ARTEC Boxer Mechanised Infantry Vehicle

- Boeing P-8A Poseidon for the Maritime Patrol Aircraft

- Boeing E-7 Wedgetail for the Airborne Early Warning & Command Aircraft

- General Atomics Certified Predator B Protector Unmanned Aircraft System

Buying without a competition, because you want to support your national industry defence industry, is commendable. It is what the United States, France and Germany do well. While the UK has a national shipbuilding strategy that views the construction of naval vessels as being vital for national security, the same is not true for combat vehicles.

What we save by purchasing equipment from non-UK suppliers can often be lost when the long-term costs of supporting it from overseas become greater than if we had used domestic firms. When we buy equipment internationally, we may not get priority treatment for spare parts or repeat orders in times of emergency. This makes competition essential.

It’s often said that armies are equipped to fight the last war not the next one, but the dilapidated state of the British Army’s combat vehicle fleet could easily lead a casual observer to note that it isn’t even equipped to fight the last war. With the mix of threats we now face, there is a risk of the Army being substantially overmatched by both the quality and quantity of potential adversaries’ military resources. With many major platforms approaching a cliff-edge of block obsolescence, we are in the unenviable position of having to replace many vehicles simultaneously while having insufficient resources to do it. All these factors increase the risk of getting new acquisition programmes wrong.

The old adage is that when it comes to procurement there are three elements: quality, time, and price. You can only ever prioritise two of these three elements. Which means if you want something of high quality quickly, it won’t be cheap. If you want something inexpensive and fast, it won’t be high quality. And, if you want something high quality and at low cost, you won’t get it quickly.

New threats have lit a fire under the Army’s modernisation efforts

The world changed in 2014 when Russia annexed the Crimea. An aggressive response to economic sanctions placed on Russia as a result, has seen all kinds of hybrid warfare activities conducted against us. With Vladimir Putin seeking to re-unite former Soviet Union states, we have been forced to enlarge the deterrent effect of armed forces. China’s aspiration to become a global superpower that rivals the influence of the United States has seen it act to dominate Asia and Africa. It also transforming its military capabilities. Meanwhile, Iran remains a major sponsor of international terrorism and has unfulfilled nuclear ambitions. North Korea remains a threat. Finally, Daesh has not yet been fully defeated while Islamic extremism is expanding across Africa. Over the last decade, the world has become more volatile and dangerous than it has been since at any time since the end of the Cold War. For all of the above reasons, there is an urgent need for the Government to fund Defence programmes that have languished in the Treasury since 2010. The need for Army regeneration has become an urgent priority. This is no longer just about new vehicles, but reconfiguring it at a fundamental level in terms of roles, missions, size, structure and capabilities.

In the light of all this, the Army needs to re-examine its modernisation plans and the acquisition programmes that flow from them and to ask itself: is what we originally planned to do still the right way ahead? If it is, then it should continue to press for the implementation of its current acquisition strategy. But if it isn’t, then the Army must have the confidence and self-belief to say: this is no longer what we need. We need to do something else.

Above all, we need the Army to think big again. We also need the Government to trust the Army to know what it needs.

The Navy has been consistent in thinking big and has been uncompromising in demanding what it believes is required to make its major programmes successful. Carrier Strike has been the focus of Royal Navy modernisation for more than 20 years. It wanted two 65,000 tonne carriers instead of three 40,000-tonne vessels, because it felt it could deliver a more effective capability. Astute Class attack submarines, Type 45 destroyers and Type-26 frigates are part of the same vision. So are the F-35B Lightning JSF and AW101 Merlin helicopter.

The RAF has also shown itself able to think big. The Tempest future combat aircraft represents a stunning vision for the replacement of the already excellent Typhoon. It follows a long lineage of excellent combat aircraft developed and operated with extreme focus and ambition. Like the Royal Navy the RAF knows what it wants. It was very clear in stating that the P-8A Poseidon was the only realistic option for its Maritime Patrol Aircraft requirement.

So where does this discussion leave current British Army programmes?

It is impossible to predict when and where the next conflict will start. Recent history has shown us that serious situations can unfold with unexpected speed and ferocity. With condensed reaction times, we go to war with the army we have not the one we would ideally like. Without wishing to over-simplify the Army’s future strategy, it must be prepared for three types of situation: high, medium and low intensity conflict versus conventional and asymmetric threats. This means it needs potent and resilient heavy armour formations that can fight anywhere and stand their ground. It also needs highly mobile expeditionary formations that have the agility and firepower needed to project power at distance. Third, it needs SF, Air Assault and Light Role forces that can deploy boots on the ground quickly when needed. This mix of Light, Medium and Heavy Forces has created a new paradigm, but with one common theme that runs through all deployment types: the need for protected mobility.

The four cornerstones of army modernisation are vehicles, weapons, communications and supporting equipment. The Army’s combat vehicles programmes are its largest area of expenditure:

Challenger 2 LEP

The ongoing need for MBTs has been established by the sheer number of tanks that remain in service across the globe. We recognise that deliberate set-piece attacks against firmly entrenched enemies are likely to be less common, but not impossible. Tanks may play a lesser role in future conflicts, but still remain the only viable solution across various scenarios. A concern about MBTs is their deployability. If they cannot be transported quickly enough from their bases to the area of combat operations, they may not arrive in time to influence the outcome of an engagement. So, if we’re going to use MBTs widely, we will depend on a fleet of Heavy Equipment Transporters (HETs).

In the short-term, we will continue to rely Challenger 2 LEP to deliver the heavy armour capability we need, because there is no obvious alternative. Rheinmetall’s proposal will deliver not only a useful life extension, but a substantially upgraded capability. It usefully includes a 120mm smoothbore gun, which offers increased penetration against threat MBTs, but also commonality with our allies. However, we need to start thinking about what comes next. We need to answer the question: will the next MBT be a development of an existing concept, e.g. a tank with reduced weight, or will it be something completely different?

There has been some suggestion that we should consider retiring Challenger 2 and gapping the capability until a next generation MBT is available. With the USA, Germany and France all working on new ground combat vehicle concepts, a new design should be ready by 2027. However, the increased number of threats we now face, there is a higher risk of needing to deploy heavy armour. If we were forced to deploy a large armoured force, but but didn’t have any tanks, we would lose all credibility. So gapping the capability simply isn’t a realistic option.

Warrior CSP

It is often said that conflict is resolved on the ground. This invariably implies the need to deploy infantry to seize and hold vital territory or to close with and defeat the enemy. Delivering infantry wherever they are needed creates an enduring requirement for protected mobility. This belief gave birth to the Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) during World War 2, which is a tracked infantry vehicle able to keep pace with MBTs. Recognition of the fact that APCs would encounter other APCs, led to the development of the Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV), which is a vehicle with a weapon capable of defeating other IFVs. Warrior was excellent in this regard when it first appeared 40 years ago. Today, as other NATO armies adopt new platforms, Warrior is showing its age. Given the ongoing importance of this class of vehicle, there is a case for acquiring a brand new IFV rather than simply plonking a new turret on Warrior.

In particular, the Warrior CSP programme has been beset by difficulties. Problems with the new turret, including the ammunition handling system and power supply, have delayed it. More important, concerns about cost of the programme mean that many fundamental issues with the platform have not been addressed, such as the need to relocate the fuel tank. This presently sits below the turret basket on the floor of the vehicle. Should it run over a mine or IED, the underside of vehicle is likely to be penetrated. This could ignite the fuel and, in turn, the cannon ammunition, causing a catastrophic explosion.

The need for increased IED protection, to fit blast attenuating seating and a new electronic architecture require a considerable re-engineering effort. At the same time, corrosion issues have reduced the structural integrity of many existing hulls, creating a need to fabricate new ones. With such an extensive number of engineering changes to the original vehicle, costs have inevitably risen. A question that many users are asking is whether the Army would be better off with a new IFV? If so, there is definitely a need to re-think this programme.

Ajax

Ajax has been acquired to replace the CVR(T) family of reconnaissance vehicles. Using the ASCOD 2 infantry fighting vehicle platform as a foundation, GDLS has engineered a brand new vehicle. Ajax’s IFV roots mean that it is much larger and heavier than its predecessor, but it has to be to achieve the required protection levels. Even so, it is a hugely capable and agile vehicle.

Ajax is fitted with a new 40mm cased-telescoped ammunition cannon. This is as innovative as RARDEN was in the 1970s. Co-developed at considerable cost with France, this uses a unique and expensive ammunition type. The UK has encountered significant development issues developing an ammunition handling system for it, while barrel life is still less than 1,000 rounds. With only three nations using CT40, you have to ask why we specified and then developed a bespoke capability at great cost when so many proven systems offering similar levels of performance were already available off the shelf?

One important feature missing from Ajax is the addition of a twin ATGM pod to counter MBTs. Obviously this extra feature is much desired by the Army, but was deleted on grounds of cost. Had we acquired a less expensive cannon, we might have been able to fit anti-tank missiles. As noted above, the upgraded Challenger 2 will switch from a 120mm rifled gun to a smoothbore gun, giving us commonality with our allies and reducing ammunition costs. We have put right one mistake with tank guns only to repeat it with cannons.

The reduction from three Armoured Infantry brigades to two (plus two Strike Brigades) means that we may acquire more Ajax platforms than we actually need to for the reconnaissance role. For this reason, Ajax will be used by the Strike Brigades as well. However, as has been made clear elsewhere, there are concerns that mixing wheels and tracks when the purpose of Strike is long-distance deployment does not make sense. Ajax will not keep-up with Boxer when deploying by road at distances over 1,000 kilometres.

Boxer

The Mechanised Infantry Vehicle programme is the latest effort to acquire a medium weight wheeled vehicle family. Paradoxically, we have gone back to the very Boxer 8×8 vehicle we rejected in 2002, which was the result of the Multi-Role Armoured Vehicle (MRAV) project and closely based on UK requirements. If we had remained a partner, not only would have Boxer entered service in 2010, but it would in all likelihood have cost much less than the price we are expected to pay for it in its evolved form.

Despite previous misgivings, Boxer has evolved into the most capable and well protected of any 8×8 currently in service. Superior to the LAV III on which the US M1126 Stryker vehicle is based and to the French VBCI, its mission module approach allows an extensive family of vehicles to be based on a common platform. There is no doubt that this vehicle fully meets the UK requirement and will be flexible enough to give us future flexibility.

The most important aspect of Boxer is that it combines operational mobility (its capacity to move at high speeds on road) with tactical mobility (its capacity to move across country). As good as wheeled vehicles are, they complement heavy tracked armour rather than replacing it. We will still need tracks for vehicles that weigh more than 40 tonnes and for use in extreme terrains.

The only real issue with Boxer is the number of variants we will acquire. If Ajax belongs in the Armoured Infantry Brigades, we will need to specify a Boxer reconnaissance variant. Not having one is a major concern as the Strike Brigades will need some form of direct fire support if they are to survive against peer adversaries.

MRVP

The Multi-Role Vehicle Protected (MRVP) consists of three separate vehicle packages intended to fulfil a variety of roles. Package 1 will replace the Panther Command & Liaison Vehicle (CLV) and Husky Tactical Support Vehicle (TSV) with two versions of the JLTV. One will be a CLV the other a TSV with a flatbed. Package 2 will be comprised of a Battlefield Ambulance (BFA) and a Troop Carrying Vehicle (TCV) designed to replace various MRAPs including Foxhound, Wolfhound, Mastiff and Ridgeback. Package 3 will be Light Recovery Vehicle (LRV) most likely based on the Supacat HMT600 platform. Ultimately, the MRVP programme will replace eight platforms with just three.

Recognising that Boxer and Warrior are expensive, adopting a troop carrying MRVP variant makes sense. It is the Army’s equivalent of the Navy’s Type 31e light frigate. Being a smaller and less heavy vehicle than Boxer will aid deployability, but MRVP is more of a battlefield taxi than a combat vehicle.

Tweaking the plan

Overall, the above vehicle programmes reflect a solid and well-considered strategic plan. They will reduce the total number of combat vehicle platforms operated by the Army from 25 to around 12. This will deliver huge savings in through-life support (TLS) and training costs. Training will also be simplified, but most important, the Army will receive more capable combat platforms across all essential roles.

Although the above vehicle programmes will deliver many advantages over the platforms they are intended to replace, there is still room for improvement. The increased cost of the Challenger 2 LEP means we will only acquire 148 instead of renewing all 227. This is a mistake. The increased threat posed by Russia implies a larger fleet of tanks. If we have fewer brigades, why not make those we do have more substantial? We would not go wrong if we followed the US Army’s Armoured Brigade Combat Team (ABCT) approach and generated square brigades, each with two MBT regiments instead of one, plus two IFV battalions. With two Armoured Brigades adopting this structure, we would need four tanks regiments or 227 Challenger 2 MBTs.

We might also consider re-adopting the original Army 2025 plan and generate three Armoured Brigades. If we did this, and adopted square brigades, we would need six MBT regiments or 336 Challenger 2s (as we had before). If we equipped regiments with 44 tanks instead 56, we could get by with 264. But, whichever way the requirement is delivered, 148 MBTs is not enough.

As noted above, the Warrior CSP programme is behind schedule, over budget and with ongoing technical issues. If it were cancelled, the money saved could be diverted towards buying the Ajax IFV that GDLS has developed for the Australian Land 400 Phase 3 competition. With a lengthened hull, this has more interior space than Warrior. Since we need fewer reconnaissance vehicles, we could reduce the current Ajax reconnaissance variant purchase to 300 vehicles instead of 589 and buy 380 Ajax IFV variants instead. This would increase the total number of Ajax platforms to 680. It would give the AI Brigades a common platform with a long shelf-life. Above all, it would deliver an exceptional capability to reconnaissance regiments and infantry battalions alike.

Alternatively, the money saved by cancelling Warrior could be diverted to buying a turreted variant of Boxer for the Strike Brigades, or another 200 vehicles. Even without doing this, we will need to acquire additional Boxers if we are to fully replace the FV432. There is talk of the UK acquiring 1,200 Boxers, and possibly as many as 1,800 in the long-term. This would be a huge win for the Army and give the utility it desires across low, medium and high intensity deployment types. It cannot be unrealistic, over-ambitious and unaffordable to want to replace a 60-year old AFV.

As things stand, the Boxer Infantry Carrier Vehicle (ICV) will only mount a 12.7mm HMG. This may be sufficient for counter-insurgency deployments, but not if we need to take-on peer adversaries. Mounting a cannon in a remote weapon station, unmanned turret or crewed turret is likely to become an increasingly important requirement.

The MRVP programme will ensure that all units that need protected mobility get it. The UK Land Power blog has already suggested that leveraging the Supacat HMT or Foxhound platform might be preferable, yet we seem committed to the US Oshkosh JLTV. If this delivers the desired utility at a good price, then it is justifiable. The Package 2 contenders, the Thales Bushmaster and GDLS Eagle, are both proven platforms in service with other armies. So whichever one is chosen is likely to be a low-risk solution. Package 3 will leverage the Supacat HMT platform, so is also aa low-risk solution.

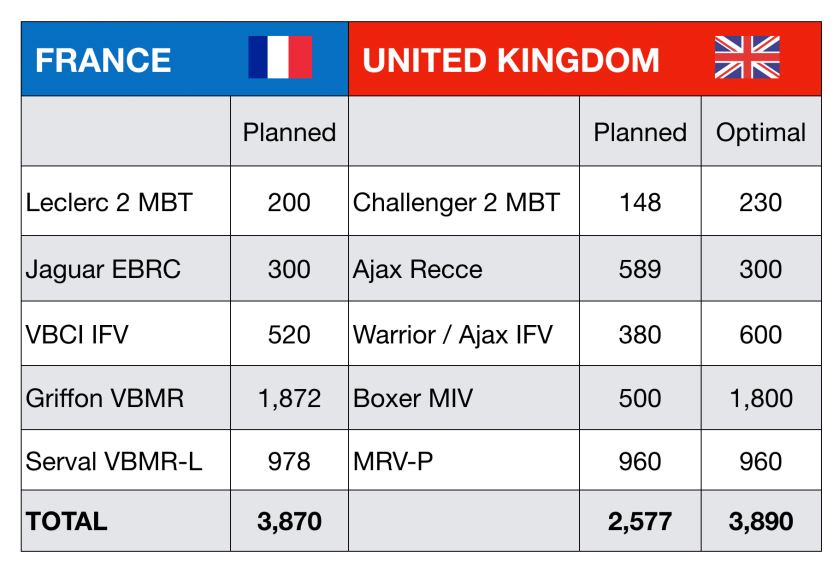

If UK modernisation plans are compared to those of France, they cannot be criticised for being over-ambitious. Tweaking numbers would give us a commensurate capability.

Thinking beyond vehicles

The second cornerstone of Army modernisation is its communication systems. The Land Environment Tactical Communication & Information Systems (LEtacCIS) programme, known as Morpheus, will replace Bowman with a new family of combat net radios and systems built around modular hardware and an open software architecture. It will ensure reliable and secure long-distance communication via voice and data. It will be linked to the Army’s Battlefield Management System (BMS via a Generic Vehicle Architecture (GVA) which is the digital backbone being plumbed into all combat vehicles. With upgradeable hardware and software, more compact packaging, longer battery life and other enhancements, it should be a big step forward. Those responsible for delivering Morpheus are conscious of the mistakes of Bowman, so hopefully they will avoid repeating them.

The third modernisation cornerstone is weapons that deliver kinetic effect. One particular area that needs wholesale re-investment is artillery. There are seven missing capabilities:

- 120mm mortar

- 155mm L/52 calibre howitzer

- Wheeled multi-launch rocket system (HIMARS)

- Long-range precision fires missile system

- Ground-based air defence (Short-range and Medium-range)

- Counter-battery detection systems

- Small UAS operated at unit level

For a long time, the UK has been out of the air defence game. If, for example, we deployed a force in Eastern Europe without sufficient GBAD assets, it would be decimated. The ubiquity of low cost drones used as reconnaissance and offensive platforms means that using effective but expensive air defence missiles such Starstreak HVM is unaffordable. So we will need to acquire some kind of air defence cannon. The Army will replace the ancient Rapier air defence missile with the SkySabre / CAMM missile system used by the Royal Navy. This is an excellent capability and having commonality across both services allows interoperability as well as saving costs. The problem is that we will have just 24 launch vehicles. We need at least 96.

The fourth cornerstone is the technical systems and infrastructure that support our primary capabilities. We also need to invest in people and training.

What will most ensure the effectiveness of Armoured Infantry and Strike Brigades is the CS and CSS assets that keep them supplied when deployed. We cannot invest in all the shiny stuff without looking and the systems and processes that enable effective logistic support.

As we look to restore potency across many of the Army’s existing functional areas, we also need to embrace new requirements. We need to develop our Hybrid and Proxy Warfare skills. We need an offensive Cyber and Electronic Warfare capabilities. We need to be able to operate within the “Grey Zone.”

As the Army tries to meet commitments across many areas, it must make smart choices. But whether it’s buying boots, body armour or batteries, it knows that buying the cheapest option often means buying the same equipment twice. So, it must tread a fine dividing line between cost and utility to ensure it delivers value.

The problem with many of the requirements listed above is the defence budget as it stands today simply isn’t sufficient to deliver them all. Based on analysis of major programme costs, it is estimated that the Army would need a minimum of £2 billion a year for the next 10 years to procure all of the equipment it wants. Is this a return to profligacy? No, it is a recognition that the defence budget now needs to grow.

[1]McKinsey on Government, An Expert View on Defence Procurement, by David China and John Dowdy, April 2010.

[2] https://www.overtdefense.com/2018/11/06/sa80-rifle-upgrade/

Very good article. Seems like everyone is being required to do more with less money these days. I understand the need to preserve national production capability but, given the fiscal realities of today, one would think there would be more acquisition partnering between allies to get systems that are “good enough” and more economical instead of going it alone for “perfect” systems that either eventually price themselves to death or march past obsolescence before or soon after they are fielded, or both.

Seems like that notion is gaining traction with the end users but politically it’s still distasteful as evidenced by the current effort to require “Build American” for out FFG(X) program, much to the chagrin of USN program leadership.

LikeLike

I was struck by the contrast between the following passage and then a sentence.

The passage and in brackets dates in office: ‘General Sir David Richards’ (from August 2009) vision when he became CGS in 2009 was an Army built around counter-insurgency warfare. General Sir Nick Carter’s (from September 2014) plan for medium weight Strike Brigades became the centrepiece of British Army modernisation. Now, General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith (from June 2018) finds himself in a position of having to re-prioritise Armoured Infantry brigades. ‘

The sentence: ‘We also need the Government to trust the Army to know what it needs.’

On that evidence alone I doubt any government would trust the Army to know what it needs!

LikeLike

A thorough and informative article, many thanks.

The Guardian did an interesting piece on the SA80, I think I laughed out loud when they handed a couple over to Heckler and Koch:

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/oct/10/military.jamesmeek

I must admit I’m confused as to how you stop or amend a programme, projects to replace legacy systems seem to plough ahead on their own paths regardless, the only thing that stops them is money. Do the Warrior and Ajax projects sit across from each other during lunch at Abbey Wood silent but unable to escape the sexual tension between them? Maybe the canteen needs a suggestion box. I think you’re right, the army are terrified that they’ll lose something if they change their minds.

Who’s in charge here? Who would have the power to make changes mid flow but be able to reassure the services. With long project times and the accelerated pace of technological and political change, somebody should really be in the position to hit a big red button and tell everyone to take a minute and look again, but without risking everything unravelling. I wonder should a body like the Defence Select Committee have greater powers, should they maybe sit somewhere in the middle holding the cash from the treasury as a trusted intermediary? It would give continuity and certainly raise the profile of defence within parliament. Should there begin a tradition of always picking your Def Sec from the committee? Should ultimate oversight be by Defence Twitter? Almost certainly yes.

The article is pretty much a long list of things that annoy me:

Why the Warrior/Ajax thing when the Warrior cost must be approaching Ajax cost. Because we have so many spare parts for warrior? Long term availability and efficiency suggests a single fleet.

Why a billion pounds for Watchkeeper when it’s straying into RAF territory and when something like Blackjack matches the range of RA’s guns and they’re (relatively speaking) cheaper than sweets and you can launch them from a truck, or from a ship for that matter.

Why JLTV, because they’re cheap? Certain things I’d pay more for, a sovereign capability on such a basic building block is one of them. First requirement is to replace 400 Panther and we have 400 Foxhound and they’re modular, so…

Even SkySabre annoys me indirectly, why do this and then look for an MLRS replacement instead of developing it along the lines of the K239 Chunmoo and putting the CAMM in MLRS pods? You’d create a system that can do anything from air defence to long range precision strike. You might even sell a few too. Potentially If we went with Archer on MAN too the whole RA could be based on the MAN chassis, availability would be through the roof.

I should be careful here as it’s your area, but for the sake of argument, why not expand the Household Division, give it all the tracks and the responsibility for generating an armoured brigade?

Put the five foot regiments in Ajax APC, put the Dragoon Guards in Ajax recce, merge the Hussars and give them tanks along with the Lancers, Blues & Royals and RTR.

It nominally restores the rule of three by allowing three brigades (and Guards Brigades at that) in tank heavy or infantry heavy formation or in extremis a square armoured cavalry brigade and is kind of a happy middle ground between what they say they can afford and what everyone else thinks we need.

It would also (and I should be REALLY careful here) kind of partition the cap badge mafia from the rest of the army. I’m of the opinion that the line infantry should form large regiments that do a lot more of their own stuff from 120mm mortars to light tanks and recce, expanding and contracting under their own banner much like the Royal Marines.

Thanks again for the excellent article.

Kind regards, Nemo

LikeLike

I believe the army is going in the right direction warrior CSP seems to be raising concerns, but latest released information from the supplier seems to state all is on track. The platform is proven and I believe it has proved it’s protection. As long as the programme stays well below procurement of another vehicle it makes sense especially with logistics parts etc. Already in place. If not pull the plug.

The main concern is for MBT numbers and STRIKE. Even if the current structure is maintained CH2 will not support training and deployment and frankly for a country our size 148 is just not good enough. Ideally your ideas about changing structure to actually increase the numbers would be good as management of mastiff and MIV fleets could look to increase troop transport/ifvs to support the MBTs.

In terms of STRIKE wheels and tracks do not mix and it would be stupid to deliver ajax via het halfway across the world when ch2 could need these in Europe! One hope I have is that rubber composite tracks may increase ajax road capability but I would doubt they would turn it into MIV.

If warrior CSP does deliver then I would seriously look to change the make up of the order for ajax and redistribute reconnaissance equipment to boxer GDLES could even produce these and then send to rheinmetall for integration.

Any remaining numbers ie non turreted could be utilised in the armoured infantry brigades either replacing mastiff or fv432. If warrior CSP does not deliver then Ajax variant should be fallback and the order amended as required, whilst boxer delivers STRIKE.

My other concern for STRIKE is that these are comparatively lightly armoured when compared to full armoured brigades yes they are more agile but current plans leave then with considerable less firepower. This needs to be rectified for several reasons perception and it’s own protection. Perception if STRIKE is to be used as an out of area capability and a deterrent then potential adversaries need to see it as a real credible force. Protection as a vanguard force strike is less likely to be operating with the full amount of air power or allied forces therefore it could easily find itself without CAS and up against full armoured brigades.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on vara bungas.

LikeLike

SA80 took even longer than you state. Development started in 1971, with the first examples issued to the Royal Marines in 1985. And of course it wasn’t actually finished.

LikeLike

I heard the marines small arm specialists who tested it found the problems with springs, magazines etc, fixed some of them on prototype weapons. However when they went into production they ignored there advice!

LikeLike

A great article, Nicholas, lucid and forceful as usual. You put your finger on the problem when you say, “Nearly all of the acquisition-related issues that the Army faces are related to money, or rather the lack of it at a time when it needs to modernise.” I’ll return to that point later.

However, there are a couple of questions I want to ask first. One concerns the Warrior CSP versus a new AJAX IFV for the IFV role. Here, I find one thing very difficult to understand. There was report only last week in the Sunday Times (Business section), which said that British Army chiefs were getting tired of waiting for a satisfactory Warrior-based solution to materialize and were likely to replace it by buying new hulls and fitting equipment to them. And yet in report in “Soldier” Magazine a few months ago, soldiers seemed to very impressed by the performance of the “Warrior 2” vehicle and everything seemed set fair for a production order! (And remember that “Soldier Magazine” is the official MOD publication for the Army). All very confusing!

You say that, if Warrior CSP “were to be cancelled, the money saved could be diverted towards buying the Ajax IFV that GDLS has developed for the Australian Land 400 Phase 3 competition. Since we need fewer reconnaissance vehicles, we could reduce the current Ajax reconnaissance variant purchase to 300 vehicles instead of 589 and buy 380 Ajax IFV variants instead.”

However, I think that the cost of cancelling the Warrior project and acquiring a brand new IFV would be something like £1 billion more – not a cheap option then. Moreover, I am fairly sure that version developed for Australia carries only six demounts. Would that be satisfactory for the British Army, whose Infantry usually works in sections of eight?

There is also the point about the need for a successor to the FV432/Bulldog vehicle. This was to have been the ABSV but that project appears to have gone into suspended animation. It is a vehicle which is very much needed for roles such as mortar carrier, ambulance, repair and recovery, etc. If Warrior CSP turns out to be no longer needed in the IFV role, is it then likely then to become the basis for a revived ABSV programme or would AJAX have to be the replacement for that too? Again you are talking a lot of money and I come back to the comment about funding mentioned above.

Anyway, a most enjoyable read! Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for the positive feedback! Much appreciated.

Just a few notes on Warrior: Since no production contract has been awarded yet, we are not on the hook for £1 billion. But we are approaching the point where we will need to decide whether it is worth it or not.

I’d expect the Army / MoD official line on the upgrade programme to be that it’s all going marvellously. But that’s why people like me write articles like this: to provide a realistic and balanced view. I honestly cannot see the point of upgrading a 40-year old design when we have the brand new Ajax.

The IFV version of Ajax is a new development of the Recce version and has been designed specifically to have space for six dismounts. It has a longer hull than the Ajax Recce version. In fact, the hull is longer than Warrior with a larger crew compartment. In reality , Warrior will struggle to fit six blast proof seats in due to the lack of space. They’ll squeeze them in, but it won’t fit 95th percentile troops.

If there aren’t enough Warrior hulls for the IFV version, there certainly won’t be enough for the ABSV version. I think it is a dead duck. If we want a basic tracked APC then we should just purchase more Ajax vehicles. This is now our core tracked. platform. That said, the Boxer8x8 is also capable of performing many of the same roles.

Ultimately, I see the UK Combat vehicle fleet comprising the following six platform types:

– Challenger 3 (replaces Challenger 2)

– Ajax (replaces CVR(T) and Warrior)

– Boxer(replaces FV432, Mastiff, and Wolfhound)

– Bushmaster (replaces Land-Rover Ambulance and Ridgeback)

– JLTV (replaces Husky, Foxhound and Panther)

– HMT (replaces Land-Rover WMIK)

That’s six types replacing twelve, which will simplify TLS and training. Overall, it is an excellent plan. The only thing that doesn’t make sense is having both Warrior and Ajax.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your illuminating reply. I suppose that I have been partly writing in the dark. For instance, I knew little or nothing about the information you reveal in the paragraph about the size of the IFV version of Ajax e.g. about how it has a longer hull than the Ajax Recce version and indeed a longer hull than Warrior. Serious question : AJAX has already come in for some criticism for its large size as a Recce vehicle. Could not that size also be a disadvantage when it is used as an IFV, for instance, in urban warfare where streets are often narrow and turning circles are restricted?

Has the new vehicle got a name yet or are these early days? “The IFV version of Ajax” seems a bit of a mouthful! Also which weapon would it carry? A 40mm cannon?

Actually, on the subject of Warrior versus the IFV version of Ajax, it would seem from Simon m’s first paragraph that he has been reading information similar to that which I gleaned from “Soldier Magazine”. He also makes a good point about spares etc. for Warrior being already available. He is also right about 148 upgraded Challenger 2s being simply inadequate for a country our size.

LikeLike

I would just like to add that I would love either a variant of ajax or even lynx AFV but I cannot believe warrior cannot do the job at the end of the day the programme seems to be going ahead.

There are plenty of 40 year old vehicles still going strong and most of them without the survivability record of warrior.

The programme (should) be cheaper and if it saves even 10 to 15% on Ajax variant then that is money that can be spent on other programmes ie STRIKE. It has to be remembered that for vehicles such as Challenger and warrior they are less likely to be straight in to battle. Most of the times they have been used they have been subject to uors and normally enter in a THES. They are also most likely to be operating with support of allies and with greater air power support in staged battles.

For this reason I think that most of the investment should go to the STRIKE brigades who will more likely to self-deploy at a moments notice with little chance of UORs being in place. Ideally this would mean Boxer in numerous variants.

For mrvp it would be interesting to know how much eagle 4×4 would cost versus jltv as if this was procured alongside the many 6×6 variants you could effectively have a 2 vehicle STRIKE brigade (plus some man trucks). This could also be said of a foxhound/hmt purchase but the government seem to want to push for off the shelf.

LikeLike

I am flabbergasted with the ostrich like behaviour of Whitehall mandarins and the lack of direction from Government. Every time we get a new CDS another new direction is taken. There is no long term thinking or planning. The Sandhurst mentality of I need to mark my career by doing something that stands out, this is what were going to do. It’s almost as bad as Baldricks, “I’ve got a cunning plan” statement! The Army seems to be stumbling on regardless and sleep walking in to the next great idea.

We have been heavily involved in contingency ops for the last 20 years, which has meant the majority of the available funds or the funds already earmarked has been diverted from peer vs peer to counter insurgency support. Contingency ops should be seen as a diversion, whereas the bulk of the force should be to counter a peer. To this end we need to put our money towards enabling the Army to be both defensive and offensive, thereby giving it the kit required to do this job.

The US Striker brigade works. However, to make it work, the brigade is proper;ly funded to be almost completely self-contained. The brigade is designed around a family of LAV vehicles, ranging from Command, Infantry carrier, mortar carrier, engineering, ambulance, communications, direct support and air defence. They are lacking in reconnaissance, bridging equipment, logistics and artillery, but the intent is develop LAV vehicles that can do this role instead of trucks.

Our Strike Brigade is a hodgepodge of wishful thinking, sounds great on paper, but has no teeth. The Boxer is the ideal multi-role vehicle that could fulfil most of the required roles. To be a true highly mobile strike force, it must be funded and kitted with the correct type of vehicles, therefore Ajax should not be part of the force.

The decline of our heavy armour, artillery and ground based air defence is a disgrace. If we deployed a suitable force to reinforce assets in Europe, we won’t have sufficient Sky Sabre units to defend both the deployed forces and key targets in the UK. If we lost the whole deployed force’s vehicles like the BEF did during the WW2, we simply don’t have anything to replace it with.

Unfortunately, there is no simple answer. It would be easy to say that the Government could Nationalise BAE System. However, the key industries have now gone. We would have to start from scratch. Which is perhaps the best long term option. But to make that work there has to be a long term requirement with sufficient numbers to make it viable.

The Navy has instigated the National Ship Strategy which was Government led, but has yet to see fruition. This has the long term goal of making sure the Navy has new ships every 10 to 15 years, as it has proven that replacements are cheaper than maintaining them over a protracted period. I believe the Army needs to go down the same route. With heavy armour, artillery, air defence etc. Design the vehicles with a shelf life of 10 to 15 years, then pass these on to reserve units and sell the excess on. This would ensure our forces have up to date kit, but also ensure there’s industry to support and replace it.

LikeLike

Ultimately, I see the UK Combat vehicle fleet comprising the following six platform types:

– Challenger 3 (replaces Challenger 2) get a new name be reasonable

– Ajax (replaces CVR(T) and Warrior) i agree but a standard platform is needed

– Boxer(replaces FV432, Mastiff, and Wolfhound) see above (im not against wheels)

– Bushmaster (replaces Land-Rover Ambulance and Ridgeback) 1

– JLTV (replaces Husky, Foxhound and Panther) 2 could these be variations on a chassis?

– HMT (replaces Land-Rover WMIK) 3

Jolly good show.

-However i think the AS90 needs an update and all the armour for the UK can you hope for 170mm with a Pz2000 style autoloader? i certainly can, i can hope. what do you think of these ideas.

-Also what do you think of a QF firing (90-105mm) gun because they did think about a common gun tube program when developing the as90 but it was scrapped due to the as90’s awkward for the naval application 3 piece ammo.

LikeLike

I am unsure we are ever going to fund a larger number of Boxers in which case would it be better to look past bushmaster/eagle? and look at a more capable 6×6 such as patria/griffon/protolab? This could potentially replace fv432 with this at a cheaper price point? If you compared the French plans and their costs against the potentially proposed British plans I would guess that the British plans would be significantly more costly

LikeLike

The elephant in the room that is skewing the army plans is Ajax.

Wrong vehicle at the wrong time at the wrong price. (£6.5 billion?)

There is one statement in this article that I could’nt disagree with more and it’s,

‘the British Army has tended to get equipment acquisition right more times than it has got it wrong.’

Ever since it parachuted Panther into the CLV competition it’s mostly got it wrong including that.

From Vector, Springer and being forced to get Mastiff.

Leaving MRAV in 2003 after the first prototypes were built in 2002 due to wanting it to be flown in a C130 which was’nt going to be our tactical transport during the vehicles service life (not to mention the vehicle can be split into 2 regardless) and then choosing a power point vehicle after the trials of truth when the other 2 vehicles were either in production or about to go into production, and we helped design one of them.

And finaly changing the priority from FRES UV to FRES Scout when even a customary look around the armies equipment would show that UV and MRVP were the most important platforms to prioritise.

LikeLike

Should we go all Oshkosh controversial and get 6×6 version of to provide the logistic elements of what bushmaster/eagle would have covered

LikeLike

I sometimes wonder whether Boxer (or any of the current crop of 8x8s) is still the right vehicle. It is close to 3 metres in height and 8 metres in length. It weighs 32+ tonnes and dwarfs many existing tracked APC and IFV platforms. And, oh, it costs £4.3 million with just a 12.7 mm HMG mounted on it. Would a smaller, less expensive vehicle like the French Griffon 6×6 or Bushmaster 4×4 be a better option? While they certainly cost less, their protection levels are vastly inferior, so it may be time to develop an entirely new concept.

LikeLike

@UK Land Power

At this point in time, I would scrap ajax. Vastly over budget for a gold plated 100% solution. Instead, I would Jump in bed with boxer and go all-in on that.

Boxers are a cheaper option in the long run and their modular design allows them to fulfil the role of an IFV and reconnaissance, even if it is just a 90% solution. The future of the army is in the strike brigade concept so here’s what I’d do:

– New MBT – with hopefully 250 tanks (Please think of a different name to chally 3!)

– Boxer (different modules and outfits. you could add a remote weapons station and turret which you talked about in your recent “Optimising UK strike brigade structures”. It would also allow for artillery modernisations at a reduced price: a 120mm NEMO mortar, a 155mm artillery piece, New MLRS based on the boxer – massively saving on training and maintenance. Another benefit is the cost savings from economies of scale)

– Bushmaster

– JLTV (Perhaps if budget allows, more firepower could be implemented by equipping a fair fraction (maybe 1 in every platoon) with an M320 30mm and ATGM, but even to me, this seems slightly on the gold plating side of procurement)

– HMT

With Different boxer variants and a new MBT making up a strike division and JLTV making up a quick reaction division/light Divison

Thus, the army would only be operating 5 different chassis types + a few specialised logistical vehicles. Saving a lot of money in the long-run.

I realise I’ve regurgitated almost everything you said in your most recent post, I do apologise!

But I would love to hear your thoughts and opinions on this!

Chris

LikeLike