By Nicholas Drummond

The Integrated Review and Defence Command Paper were a necessary reset of UK defence priorities. In order to make defence affordable and sustainable going forward, short-term economies were necessary. This resulted in various programmes being deleted, delayed, or scaled back. Despite being the force most in need of modernisation, the Army was most affected by what many view as a cost management exercise more than force optimisation plan. The question is whether Russia’s invasion of Ukraine now invalidates IR and DCP assumptions, and whether Army modernisation should now be accelerated.

Contents

1. Introduction

2. Army modernisation – Out of step with pacing threats

3. Wrong-footed by Putin

4. Potential outcomes in Ukraine as guide for UK defence initiatives

5. Practical next steps

1. Introduction

British defence reviews rarely survive the first international crisis that follows them. Within seven days of the 1990 Defence White Paper being announced, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and an entire armoured division that had sat dormant in Germany for decades was used in anger. The 1998 Defence White Paper was never properly implemented due to 9/11 and the subsequent War on Terror. This saw forces deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, while reorienting the Army around counter insurgency operations. Now, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has questioned the validity of the 2021 Integrated Review and Defence Command Paper within months of their publication.

Although the 2021 Integrated Review correctly identified Russia as the principal threat, it did not anticipate that Putin would follow-up his annexation of Crimea with further aggression. The underlying narrative was more about promoting post-Brexit, Global Britain than maintaining a European focus. It acknowledged China’s burgeoning superpower status through a “tilt” towards the Indo-Pacific rather than an outright “pivot.” Behind the strategic context, the Integrated Review was an attempt to force the three services to live within their means and drive improved efficiency in the management of essential modernisation programmes. Many existing problems stemmed from overcommitment. So, instead of trying to perform an extensive array of defence roles to a mediocre standard, the goal was to define a more focused range of priorities, resource them properly, and deliver excellence across these key areas.

A necessary part of this re-set was balancing the books. This inevitably meant deleting, delaying and scaling-back modernisation plans until more money could be made available. The Army was the biggest loser with headcount slashed by 9,500 soldiers. Challenger tank numbers dropped from 227 to just 148. The Warrior infantry fighting vehicle was axed altogether. The RAF lost 24 of its older Eurofighter Typhoon combat aircraft, while the Lockheed C-130J Hercules fleet is to be retired early, diminishing our strategic transport fleet. Only 3 E-7 Wedgetail early warning aircraft will be acquired instead of 5. The Royal Navy did not lose any ships, but there has yet to be a firm commitment to purchase additional F-35B joint strike fighters beyond the 48 already agreed. The RN and RAF may get 66, but this is a far cry from the original anticipated total of 138. UK Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, described the Defence Command Paper as “putting our house in order.” It was certainly this, but it was cost management exercise more than a force optimisation plan.

In fairness, the economic impact of Covid-19 had made further short-term belt-tightening across all areas of government unavoidable. Britain’s delayed response to the outbreak showed that if any part of the defence establishment needed additional investment it was national resilience. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, contingency planning for the NHS was the main priority. Post-invasion, securing oil, gas, and other energy supplies, protecting vital infrastructures, and ensuring that UK food production is sufficient to feed the nation in the prolonged absence of imports, have all become more important than buying more warships and aircraft.

However, there is no escaping from the fact that delayed modernisation, especially for the Army, has resulted in serious capability gaps. Equally important, with so much of defence discussion focused on equipment, it’s easy to forget that defence is about much more than military hardware. Logistical planning, building-up reserves, recruitment, training, and ongoing support are all resource intensive. Being prepared is not about buying new stuff, it is making sure that everything already in service is fully operational and making sure we have enough war stocks to fight for more than a week.

2. Army modernisation – Out of step with pacing threats.

The piecemeal allocation of budget since 1990 has steadily eroded the mass and combat power of the British Army. Atrophy might not matter if force generation were more easily and rapidly achievable, but manufacturing new equipment and building-up reserves takes time. In contrast, modern conflicts unfold with unexpected speed and ferocity, which means we go to war with the Army we have, not the Army we would ideally like. It is worth remembering that Britain was largely unprepared for war in 1939. Even with American support, it took three years for industry to ramp-up. Consequently, we were forced to fight a much longer and more costly war than we would have done had our armed forces been better prepared at the outset.

The Army is the most difficult of the three services to manage. It has the largest headcount. It is the most complex organisation with the most moving parts. It is difficult to use on operations, because logistical support is so resource intensive. It is the force most in need of modernisation, yet it is the one that most lags behind the others.

The most disappointing aspect of the Integrated Review is that it proposes further cuts at a time when the Army’s armoured vehicle fleet is approaching a cliff-edge of block obsolescence. The FV432 armoured personnel carrier is still in service after almost 60 years of continuous use. This is the same as the Mark IV tank, which appeared in 1917, still being used in 1977. The CVR(T) Scimitar reconnaissance vehicle is 50 years old. The Warrior IFV is 40 years old. The Challenger 2 main battle tank is a youthful 25-year old, but can trace its origins back to the Chieftain tank of the 1960s. Because modernisation has been delayed so long, upgrade programmes have needed to be extended scope, increasing cost, risk and the time needed to deliver them. The cost of upgrading the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle ballooned to the point where the programme was uneconomical. It made more sense to acquire a new-build vehicle than to refurbish the existing fleet, but this was considered unaffordable. Instead of acquiring a new IFV, the capability will be deleted. The decision was justified on the basis that tracked IFVs are no longer relevant to the way we expect to fight. In reality, it was about cost.

To a certain extent many of the Army’s problems are self-inflicted through the mismanagement of key programmes. But with modernisation delayed by successive governments, by 2020, it was managing six major programmes simultaneously. The pressure this placed on the delivery organisation was enormous. Delaying programmes may help to relieve the burden in the short-term, but cancelling them completely as if to punish the Army for its mistakes is self-defeating.

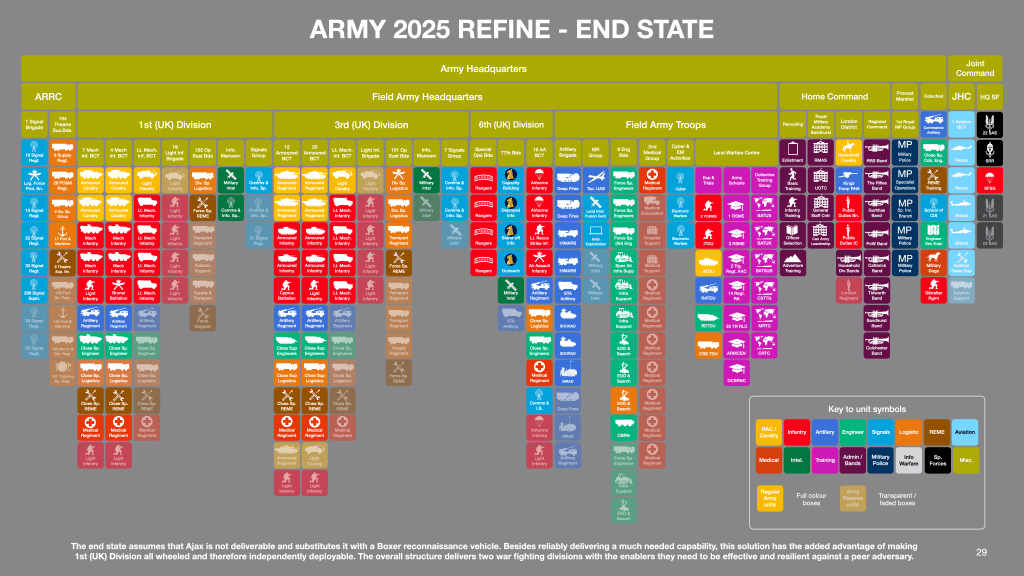

The Army 2025 plan envisages three primary divisions supported by Field Army Troops and Home Command. The overarching structure provides a solid foundation on which to build. Unfortunately, the component formations are hollow. The 1st (UK) Division has only a single deployable light mechanised infantry brigade. It has other assorted infantry battalions, but these lack artillery, engineer and other enablers. The UK’s primary war fighting division is 3rd (UK) Division. This will include two hybrid armoured brigades with a mix of Challenger 3, Boxer and Ajax. A further deep strike reconnaissance brigade is envisaged, but this an artillery brigade with Ajax reconnaissance vehicles and no logistical support assets. 6th (UK) Division has four smaller Ranger Regiment battalions plus 77 Brigade, a small information manoeuvre unit. Finally, there is 16 Air Assault brigade. In total, the Army has just four deployable brigades. This is not credible.

The creation of the Ranger Regiment provides an uplift in SF and SOF troops through four smaller battalions. This is inconsistent with reduced headcount, because we may not be able to recruit sufficient numbers of élite soldiers from within a smaller army. There are four further Security Force Assistance Battalions, also with reduced headcount. Of the Army’s total of 31 infantry battalions, only 23 are proper infantry battalions. This is not credible.

Army 2025 emphasises fighting the Deep Battle over the Close Battle. This involves the use of long-range tube and rocket artillery, as well as precision guided missiles, to defeat adversaries at stand-off distances. It is a sensible approach to counter the mass of Russia (and other potential peer adversaries). However, the Royal Artillery, will have only 5 regular field regiments, 2 deep fires regiments, 2 air defence regiments, 2 UAV regiments and a counter-battery radar regiment. This is not credible.

The belief that we can fight the Deep Battle at the expense the Close Battle is also misguided. Any army that wishes to seize and hold contested territory has to be able to fight the Close Battle. The most worrying aspect of Army 2025 is that we appear to be deleting our combined arms manoeuvre warfare capability. Without it, our capacity to retake lost ground or to partner with key allies will be severely limited.

Under present plans, combat formations mix wheels and tracks, meaning they deploy at the speed of the slowest vehicle. This compromises rapid reaction or any kind of expeditionary operation. The Ajax reconnaissance vehicle is already five years late and having encountered unreserved development issues, it is not clear when it will be delivered.

The lack of protected mobility for infantry is also a concern. Only 8 Regular Army infantry battalions out of 31 have MRAP vehicles. The MRVP programme to acquire a less expensive fleet of protected vehicles has been delayed five years.

Assuming a nominal headcount of 5,000 personnel for a typical brigade, an Army of 72,500 really ought to be able to generate more than four 4 or 5 such units. Many of our European allies in NATO have 8 or more brigades. Ultimately, the Army 2025 structure is an uneasy compromise forced upon the Army by budget considerations, not UK defence priorities.

3. Wrong-footed by Putin

Russia experts were convinced that Putin’s threats were no more than a shaping exercise designed to achieve his political goals through bluster and bluff. They could see no advantage to an actual invasion and therefore decided it was a remote possibility. It is now clear that Putin had planned the invasion some time ago and still has every intention of absorbing Ukraine within an enlarged Russia, if he can. While national resilience still deserves to be a higher priority in UK defence and security planning, it is essential to see Putin’s aggression for what it is: the most serious international crisis we have faced since the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

The immediate reaction of Germany’s new government was to reject decades of indifference by allocating an additional €100 billion to reinforce its armed forces’ capabilities, beyond its existing budget of €46.9 billion. Hawks within the UK, many whom sit on the Government’s own back benches, believe that Britain should follow Germany’s example. However, ministers have been be quick to point out that Britain is now the third largest defence spender globally after the USA and China. Even if Germany and France now spend more than us, Britain’s budget of £46.5 billion (€55.9 billion) would still place us among the top 10. The Government’s view is that if Britain is already spending an agreed 2% of GDP to support its defence commitments, there is little need for a budget uplift beyond what has already been allocated.

The long lead times associated with the development and manufacture of ships, aircraft, and land systems, mean any new capabilities ordered today would take several years to be fielded. In other words, we are already too late. If increased spending would be too late to influence the current conflict, does this mean we should do nothing and carry on as normal? Or do we need to recognise that the world has changed? If we want to prevail in a more unstable and uncertain environment, doing nothing and waiting could be a risky strategy.

Our next step has to be the development of a robust hypothesis about how the situation in Ukraine is likely to evolve and then adjust our defence commitments and priorities based on the most likely outcomes. But this is not to advocate a blank cheque approach like Germany. We simply need to fill the most obvious gaps.

4. Potential outcomes in Ukraine as a guide for UK defence

This article was written six weeks after hostilities began. Even at this point, it is difficult to predict how the situation will evolve. When the invasion started, it was widely assumed Ukrainian resistance would collapse quickly. However, even Putin underestimated Ukraine’s capacity to defend itself. Ukrainian forces have fought with courage and determination. Casualty estimates have been difficult to substantiate, but consensus estimates suggest that more than 15,000 Russian soldiers have been killed with twice that number injured. The Ukrainians say they have destroyed at least 600 Russian tanks more than 1,400 other armoured vehicles. Attacking across multiple fronts instead of a single axis, Russian Army adopted a flawed strategy, implemented it with bad tactics, poor leadership, disastrous logistics, and then failed to adjust the plan quickly enough when it proved unworkable.

Russia has paid a heavy price for its mistakes. A failure to achieve its military objectives while suffering unsustainable casualties has damaged Putin’s reputation within Russia, while global condemnation of the invasion has damaged him outside Russia. However, he has a firm grasp on power and has shown himself to be capable of eliminating any threat to his authority and control. His inner circle consists of equally ruthless individuals. Should an opportunity present itself, they might try to oust Putin, but so far there is no sign of his position weakening. Regardless of the situation on the ground, Putin is unlikely to admit defeat. He will reinforce efforts to achieve his goals. For the moment, it would be dangerous to perceive the current drop in the tempo of combat operations as anything more than a strategic pause. With more than 90% of the initial invasion force committed to the invasion, these units are now exhausted and need to be replaced by fresh troops. Once the rotation has been made, we can expect a renewed assault to take place. Despite losses, Russia still has considerable military resources at its disposal, so should not be written-off.

In the medium-term, Putin has two choices. He can either stabilise the situation or escalate it. These translate into four potential outcomes:

- Russia is defeated. Ukraine forces prevail, with the level of casualties inflicted upon Russia giving Putin no alternative but to withdraw troops. Potentially, Ukrainian forces could counter-attack, recover lost territory and revert to the status quo that existed before the invasion. This option does not exclude a further strategic pause that would allow Russian forces to regroup and try again.

- Stalemate. Putin commits additional resources and engages in a new offensive that is again defeated. This could lead to a costly and protracted war of attrition through which Russia would seek to wear down Ukrainian resistance and break its economy. Alternatively, Russia could announce that it has achieved its objectives and stand firm on the new borders defined by the limited territorial gains it has achieved. Either way, continued Western support of the Ukrainian war effort is likely to blunt further Russian offensives to the point where hostilities effectively cease or are maintained only at a very low level. As with the option above, this option does not exclude a further strategic pause that would allow Russian forces to regroup and try again.

- Russia is victorious. Putin commits additional resources, ramps-up offensive action, defeats the Ukrainian Army, and takes control of key cities. This is likely to be a short-lived success, because a Ukrainian insurgency would undoubtedly emerge, miring Russia in a second Afghanistan. This would be supported externally. It would be a long and bloody campaign. Ultimate success would be elusive.

- Russia escalates. Putin changes the narrative and decides that NATO’s contribution to Ukraine represents unacceptable interference. He could retaliate by attacking a NATO alliance member, or by using weapons of mass destruction (WMD) either against NATO countries or in Ukraine. He will certainly use threats of escalation to try and achieve political advantage.

Some Russia analysts have described these outcomes as: Lose sooner. Lose later. Lose small. Lose big. Any of the first three scenarios is likely to be inconclusive. They all imply a new Cold War with Russia, with Ukraine acting as a buffer zone. Without regime change, we will be locked-into a stand-off with Russia for as long as Putin remains in power. Assuming he dies of natural causes, he could remain president for at least another decade. Even when he goes, there is no guarantee that the person who replaces him will be any different.

There is also the possibility that Putin will not fail in Ukraine. If he fully mobilised Russian armed forces he could overwhelm Ukraine. Should he succeed, he may decide to broaden his ambitions. He could try to subsume another former Soviet satellite, such as one of the Baltic States.

Putin has threatened the use of WMD. They remain not only a defensive weapon of last resort, but an offensive weapon that gives him freedom him to do whatever he wants via nuclear blackmail. Would Putin actually unleash nuclear weapons in Ukraine or against NATO? Would his inner circle try to prevent him from doing so? It goes almost without saying the use of any kind of WMD would lead to a much wider and more serious conflict. China could reasonably be expected to become involved. We have always assumed that the impact of a nuclear weapons would be so devastating that no rational government or leader could be expected to sanction their use pre-emptively. Even if we assume that Putin is still rational, he does not think like Western leaders. He has different values. It’s not clear what Putin might do to prevent defeat or when defeat stares him in the face. Does this mean, in a worst case scenario, we would abandon Ukraine to prevent WW3? These are all difficult questions to answer. Being faced with a nuclear-capable rogue state is what makes this situation so challenging. We should be in no doubt that no one wins a nuclear war. With high stakes and no end game visible at this point, our strategy and the military tools we use to achieve it must give us maximum flexibility.

Ultimately, Putin is an authoritarian dictator who only respects the strength of hard power. If we want to avoid a nuclear exchange, then our own hard power capabilities must send a determined message. This shifts UK priorities towards being prepared for land warfare in Europe. We must also be prepared for the unexpected, which is another potential adversary using NATO’s preoccupation with Ukraine to do something elsewhere, such as China invading Taiwan, or Iran attacking Israel.

5. Practical next steps

The UK’s Trident ballistic missile submarine fleet is the ultimate guarantor of national security. If we deplete our conventional forces to the point where we are wholly dependent on the nuclear deterrent, we risk having no other response to aggression. At the very least, adequate conventional forces allow progressive escalation and negotiation before resorting to a nuclear option.

An immediate response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the imposition of further sanctions, but these are not a complete answer. Russia is used to hardship and more than able to survive independently without imports. Although sanctions are likely to cause significant long-term damage to its economy and further suffering among its people, Russia may become another North Korea rather than collapsing completely. It is reasonable to assume that Putin expected additional sanctions as an inevitable consequence of the invasion and these have already been factored-in to Russia’s military risk calculus. In any event, it may be some time before the full weight of sanctions achieves meaningful impact.

Balancing the above factors, there is a strong case to reinforce the UK’s land warfare credentials. As already noted, the Army is the service most in need of accelerated modernisation. The challenge is to add teeth to its outline structure by generating two proper war fighting divisions.

The proposed Army 2025 structure provides a robust framework on which to build. We should start by reconfiguring the Army’s two primary divisions so that they can field a total of seven combat brigades as follows:

- Two armoured brigades with Challenger 3 plus a new IFV

- Two medium brigades with Boxer

- Two light mechanised infantry brigades with MRVP (deployable with Army Reserve enablers)

- One air assault brigade with Chinook and a new medium helicopter.

This structure replicates the US Army’s four brigade types (Armored, Stryker, Infantry and Airborne) and would enable UK brigades to operate effectively in partnership with equivalent NATO units. To increase the total number of deployable brigades would require additional Regular Army engineer, logistics and medical regiments. Total Regular Army headcount would need to be maintained at 80,000 personnel to achieve this, rather than being cut to 72,500, as proposed by the Defence Command Paper. If additional budget were available, the total number of infantry battalions could be usefully increased from 31 to 34. Ultimately, an optimal peacetime establishment is 90,000, plus 30,000 Army Reserve personnel. It is accepted that this is not feasible at the moment, but it should be a long-term aim.

Infantry mass could be restored by re-roling the four Security Force Assistance battalions as regular infantry battalions. The Ranger Regiment should be sufficient to perform all training and mentoring roles, as well as special operations roles. 16 Air Assault brigade should be moved to 6th (UK) Division, effectively turning this into a special operations division.

Key equipment investments would include: upgrading 200 Challenger 2 MBTs to the Challenger 3 standard instead of 148; an off-the-shelf purchase of 600 new IFVs; plus an acceleration of the MRVP programme to ensure 20 out of 31 infantry battalions have protected mobility. Secondly, we need to expand the recapitalisation of the Royal Artillery, increasing it from 12 to 16 regiments. Additional capabilities would include two further G/MLRS (rocket artillery) regiments and two further air defence regiments.

The Army also needs to invest in loitering munitions. There is no programme of record yet.

None of these initiatives would curtail other modernisation plans already underway, including robotic combat vehicles, improved C4I systems, upgraded infantry weapons, and new mobile artillery systems. A major question is what to do with Ajax? We are still waiting to hear whether the programme can be salvaged, how long it will take, and how much it will cost. If Ajax cannot be delivered within an acceptable timeframe, then a Boxer-based turreted reconnaissance vehicle would potentially be the least expensive and most rapidly achievable alternative.

In summary, a mix of tracked and wheeled vehicles, in light and heavy brigades, supported by further investment in tube, rocket, and missile artillery, would give the Army an extensive range of flexible capabilities with utility across a variety of deployment scenarios. Wheeled medium and light mechanised brigades would deploy rapidly in expeditionary roles. Heavier tracked armoured brigades would provide a peer war fighting capability and interoperability with other NATO partners. In case any of these proposals seem unrealistic or unaffordable, they are less extensive in scope than the modernisation initiatives being undertaken by the French and German armies. Above all, they would enable the British Army to regain the mass and combat power it lacks today.

________

The problem with having to many different kind of brigades is that you can´t plan a sustained deployment (=rule of three). UK should aim for two divisions, each with three identical deployable and self-sustained brigade combat teams and a combat support brigade.

3rd Division´s brigade combat teams:

– Brigade headquarter battalion

– Cavalry regiment (2 sqn CR3, 2 sqn new CVR(T))

– Armored infantry battalion (New IFV)

– Mechanized infantry battalion (Boxer)

– Mechanized infantry battalion (Boxer)

– Artillery battalion (New 155 mm)

– Engineer battalion

– Combat support battalion (Logistics, Reme, Medical etc)

1st Division´s brigade combat teams:

– Brigade headquarter battalion

– Cavalry regiment (Jackal2 or JLTV)

– Infantry battalion (Bushmaster)

– Infantry battalion (Bushmaster)

– Infantry battalion (Bushmaster)

– Artillery battalion (L118)

– Engineer battalion

– Combat support battalion (Logistics, Reme, Medical etc)

Air Assault Brigade in 6th Division sounds good.

LikeLike

You are right and I would very much like the Army to have three identical brigades in each division. Unfortunately, I do not see this as being affordable in the short-term. Instead, the proposed structure adds a third brigade that is a light mechanised infantry formation. This facilitates a limited force generation cycle. Not perfect, but it would allow unit rotation.

LikeLike

Yes you can. However you are then regularly deploying units of less than Brigade size, which is what happens in the real world anyway. This is what the French do with generating their GTIA. if you have true all arms Brigade Combat Teams (BCT’s) then you must organize your units and sub-units with a force generation cycle in mind – do you want 1 in 3, or better 1 in 4? So each BCT can provide 1 All Arms Battle Group at:

1. Basic training, equipment reset, integration of new recruits

2. Advanced collective training

3. High Readiness including taking part in large scale exercises

4. Deployed – be that NATO EFP BG in Estonia, Cyprus, Kenya etc…

Nicholas has a draft article from me on how both our allies and our enemies have all moved to force generation based around (mostly) permanently assigned all arms formations, and this is where I think we need truly massive reform. We need to stop worrying about the mess silver, and whether the Coldstreams have better buttons than the Grenadiers……

LikeLike

1 in 4, the organisation at the beginning of that cycle would be completely different to the one at the end, churn. Our posting cadence would have to be significantly extended for this to be feasible.

LikeLike

I believe only a 1 in 3 is necessary as how the US does, yet the US is moving away from BCT structure and towards fighting at divisional level again with a peer enemy (Russia). Even Germany plans to have 8 brigades and a corps HQ by 2035.

LikeLike

Things have been on a downward spiral over the last two decades regarding army procurement. You forget the Stryker has been in service with the US since 2002 and our respective FRES programme completely failed. Regeneration of armoured vehicles has failed time after time.

This has become more apparent recently with the cancellation of Warrior CSP which was completely driven by funding rather than any capability considerations. The Ajax programme is another fiasco.

We’re told that the army no longer require an IFV yet all our allies are replacing theirs. Warriors in Estonia show that it’s still a much needed requirement.

I really hope Ajax can be salvaged – but is looking doubtful. We’ve already established Boxer as a reliable platform so Boxer CRV would be a good replacement.

We also desperately need a new IFV and should look closely at the Land 400 winner. This would allow us the army to have armoured and wheeled mechanised brigades together. Rather than either or at the moment.

LikeLike

“the economic impact of Covid-19 had made further short-term belt-tightening unavoidable”

I’m not quite sure how an extra £16.5 billion over four years represents belt tightening?

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/nov/18/boris-johnson-agrees-16bn-rise-in-defence-spending

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-to-announce-largest-military-investment-in-30-years

Surely the point is that the various aspects of defence have been re-prioritised, and the question is whether those priorities remain valid?

LikeLike

This comment relates to belt tightening across all areas of government. It should be noted that the extra £16.5 billion over four years is actually a 2% cut on an annual basis. How come? If the defence budget is based on 2% of GDP, and GDP increases each year, then it follows that that the defence budget should also increase. It has, but not by as much as it should have done based on the uplift in GDP. The increase is smoke and mirrors.

LikeLike

Thanks for your clarification Nicholas. For several reasons I won’t go into I disagree with you on this one point.

BTW I wouldn’t mind £16.5Bn of smoke and mirrors in my bank account.

LikeLike

You would mind if someone owed you £18 and only paid £16.5!

LikeLike

The concept of a twentieth-century conflict in Europe in the twenty-first, would have been viewed as a work of fiction just a year ago. How quickly did the inadequacy of the UK army appear once the invasion of Ukraine began? The wanton disbandment of the UK’s MBT force and the slaughter of Warrior included in the recent review, suddenly looked like military suicide. In truth, not one armoured vehicle earmarked for scrapping should be cast, instead, an immediate reversal of policy and a rapid upgrade with advanced active armour should be fitted to the entire fleet. Many of the current fleets can be uparmoured as seen in Iraq, but additional advanced systems such as Trophy or equivalent must be considered for all active CH2s, Warrior, and Bulldog. Boxer can not be included in these emergency actions, as too few are available, and CH3 will need to be shelved until such times circumstances allow the release of CH2 hulls. Many current armoured vehicles are in the hands of private buyers across the country, and I can see a case for reenlistment. Most will be in a better state of condition than when they were decommissioned. If it were down to me, these actions would be implemented with the utmost urgency, as we simply do not know if Russia intends to keep its actions contained within Ukraine? What I am proposing is feasible and consolidates what we have right now, and makes the best of it, by using good old British initiative. Such actions worked in WW2 and application of the same logic is the least we can do. Okay, if the war were to end in a week or two, such aforementioned actions might appear to be precipitate. However, at least we would have reversed the decline and hopefully recalibrated Whitehall thinking. Whatever the outcome, we must not dither or second guess the mentality of Russian thinking, even if it has faltered somewhat, history teaches us not to underestimate the mind of a cornered dictator.

LikeLike

Thank you for articulating many of my thoughts. Any reduction in Army headcount, while Ukraine fights for its very existence, would be criminal negligence on the part of this government, as we have no idea what Putin will do next.. I know people like Tobias Elwood would echo your conclusions, maybe even go further, but I have no confidence that the ‘cost cutting’ exercise will be stopped.

LikeLike

I understand the sentiment but assuming the slug of cash to generate and maintain the formations you suggest isn’t available, wouldn’t one prioritise any new resources?

For example would you not first check that you’ve got enough GBAD to help assure control of the air, and if not then fix it? Wouldn’t one then go onto looking at whether deep fires and ISTAR is sufficient for one’s planned force structure and do the same? Likewise for logistics and medical. Before then creating more close combat units and formations wouldn’t one then assure sufficient protection, lethality, mobility and sustainability of the planned manoeuvre brigades? I’m certainly not suggesting that the above isn’t the only prioritisation model but I would suggest that one would need to take a rigorous, systematic and stepwise approach to turning any future new financial resources into enhanced deployable forces.

LikeLike

Italy has a much smaller budget, it has a similar (now slightly larger) sized army. It has capabilities we do not, for example land based Aster 30 SAMP/T long range SAMs, down to tube launched UAS on its Frecia wheeled armoured recce vehicles.

France has a similar budget and force size, they have pursued their Scorpion programme with a singular focus – a progamme which in effect encompasses the UK’s MORPHEUS, Ajax, MRV-P and Challenger 2 update, MMP ATGM plus more. Have they had some hiccups, sure. Is it a successful programme though? Far, far more successful than anything the UK has done for decades.

Two countries with quite different foreign policies, different focus for their force posture, more or less focused on European theatre or global deployment. Probably both with their own issues and problems, and yet, both with such better equipment programmes (the programmes themselves, not arguing the efficacy of specific vehicles).

All to say that our problems are not just caused by the HM Treasury, but that the Army’s culture, its inability to develop and communicate a strategic vision without high frequency of stop-start-all change events, is also a massive part of the problem. To gain an army “fit for purpose” we need to examine and address that culture, and probably that of the MOD and DE&S and other agencies involved in decades of miss-management.

LikeLike

I think one thing that people haven’t noticed regarding the apparent ineffectivness of the Russian forces is their Battalion Tactical Groups (BTG). As a organisation it would appear that they lack the critcal mass in terms of infantry to enable combined arms warfare, meaning that the Russians can’t take advantage of their superior forces. This seems to be especially noticeable in the urban environment when BTG are tasked with both attacking and defending their tail, it would appear as though they can’t do both at the same time. I think some lessions on future soldier could be learned here, but disregarding the use of heavy armour and motorisation as some have would be foolish.

LikeLike

Not too long ago that armchair internet warriors were salivating over Russian battalion tactical groups, saying they were unstoppable and how the British and other armies would be rolled over by them; and berating anyone who thought differently.

LikeLike

“Total Regular Army headcount would need to be maintained at 80,000 personnel”

I haven’t checked back to when the headcount was last up at 80,000, but here are the recent numbers for full time trade trained strength (FTTTS) and reserve trained strength.

FTTTS Reserve

01-Jul-20 73,780 27,290

01-Oct-20 75,310 26,950

01-Jan-21 76,350 26,920

01-Apr-21 77,200 26,940

01-Jul-21 77,820 26,510

01-Oct-21 77,530 26,350

01-Jan-22 77,380 26,170

If you want 80,000 then that is a significant recruiting project, as it has been, and it has been unsuccessful.

LikeLike

“If Ajax cannot be delivered within an acceptable timeframe, then a Boxer-based turreted reconnaissance vehicle would potentially be the least expensive and most rapidly achievable alternative.”

Army 2025 Refine diagram shows 4 armoured cavalry units with a Boxer image, all under 1st (UK) Division. These look like the units currently planned to receive Ajax. If they do receive Ajax, then you have 2 brigades each with 2 Ajax regiments and 2 Boxer battalions.

Really?

LikeLike

The previous Army 2020 plan developed by General Sir Nick Carter, proposed two brigades with Challenger and Warrior plus two brigades with Ajax and Boxer. I have always been uncomfortable about mixing wheels and tracks in the same brigade. I would much prefer 1st (UK) Division to have only Boxer and no Ajax. If 1st (UK) were to become an exclusively wheeled Boxer + MRVP division, and if the loss of Ajax were to lead to a new tracked IFV to operate with Challenger 3 in 3rd (UK) Division, this would be a win-win for me.

LikeLike

An alternative line of thinking that’s likely to be not very popular: suppose its Ukrainian invasion has irreversibly weakened Russia, which economically, culturally, diplomatically and politically cut off from the civilised world and ends up increasingly strategically dependent upon China, increasing the latter’s power. If this does turn out to be the case (and it is a real ‘if’ I admit) then might that not then cause a further tilt towards the Indo-Pacific with UK defence re-balancing likewise? For the army the outcome might then look less like that proposed in this article and perhaps even more like a suped up Future Soldier. I’m not saying this will be the case, nor advocating so, and I admit this scenario is hypothetical. However the armed forces and the army’s strength, structure and modus operandi will need to match the perceived threat and the west will need to both understand the new enduring strategic reality (whatever that might be) quickly and look at various course of action to address it.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments. There are many potential outcomes beyond those I have outlined. Whatever happens, I tend to think Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will lead to regime change within Russia. Whether Ukraine wins or loses, in the short-to-medium term, we are certain to see a new Cold War stand-off between NATO and Russia. China could decide that it is its interests to support Russia. In any event, I do not see a quick resolution to the problem that is Putin, unless he starts chucking WMD into the mix. In which case, all bets are off. We should expect a state of heightened tensions in Europe to persist for some time, bearing mind that it could be as long as a decade before Putin goes. I hope he will go sooner, but unless regime change comes from within Russia, I don’t see NATO triggering it. We also need to be aware that the person who replaces Putin could be equally unpleasant.

Once Russia is brought to heel, you are right though, all focus will switch to China.

LikeLike

I have come to this article rather late but I hope that the discussion has some way to run yet. I would like to congratulate you on it being a first-rate piece of writing, encapsulating all the key issues and with some shrewd suggested solutions to the problems.

One point on equipment intrigued me. You say: “The Army also needs to invest in loitering munitions. There is no programme of record yet.” It does seem rather strange that before any announcement that the UK is intending to procure such weapons has been made, a statement has been released that we propose to supply such weapons to Ukraine. Do not get me wrong. I am right behind the plan to bolster Ukraine’s weapons to the fullest extent possible but the failure to mention the UK’s intention to procure such weaponry (if such a plan exists) is rather puzzling. Is it still under wraps, hush-hush or whatever expression is used nowadays?

If we do obtain them, would their numbers justify the creation of a new Artillery regiment, specialising in such munitions or would the required personnel be absorbed into ,say, one of the (G)MLRS regiments?

Second, with all the discussion about the possible use of chemical weapons in the Ukraine, wouldn’t it be sensible to bolster our somewhat meagre CBRN capabilities (only eight Fuchs vehicles, for instance)?

LikeLike

I’m also rather late to this article, but just watching Mr Drummond with interest on Forces News and decided to look in.

I think the conflict thus far has actually posed something of a risk to the reconstitution of the British army’s hard power as it kind of proves up some previous assumptions. From a UK political perspective our engagement through ‘Orbital’ and subsequent support is seemingly a great success, as also with the West’s control of the narrative and its punitive sanctions.

We might now look able to turn solely to the Pacific (especially with 1SL now CDS) if the army is no longer seen as a much needed counterweight in Europe due to Russia’s military credibility basically imploding in the face of light infantry.

However (and returning to Forces News), Russia is no longer of the mistaken belief that they’re liberating Ukraine, if they’re able to narrow their focus (under the newly appointed general Dvornikov) to the encirclement and annihilation of the Ukrainian corps around Donbass, it may be the wake up call we were expecting.

LikeLike

@Captain Nemo – you said “if the army is no longer seen as a much needed counterweight in Europe due to Russia’s military credibility basically imploding in the face of light infantry”. While I would use different words I think the point you are raising is against whom is the British Army designed to fight: a) the pre-Feb 2022 Russian army, b) a future Russian army that has been defeated in Ukraine, c) a future Russian army that is fixed in Ukraine indefinitely, or d) the Russian army is no longer the driving threat and another threat determines British capabilities and structure? The solutions to a, b, c & d will all be different and the question is by how much?

LikeLike

Hello Ian, my apologies for the delayed response.

Prior to the review – as I’m sure you’ll have seen – there were various conversations regarding definition, the army was seen as needing a pertinent explanation of its existence that would carry over for budgetary purposes. Most seemed to agree that the army should define itself as (and equip as) a European land power, leaving that other stuff to the navy. After all, what are we going to fight Russia with, rangers and laptops? Yet here we are and heavy metal parked in Europe now might be looking like prescience or a bad bet.

Right or wrong I was in the… ‘flanking camp’ I guess you would call it (?) weighted and budgeted for a worldwide role that could also move fast for NATO, leaving all that heavy stuff to the central Europeans, who are happy where they are anyway.

My main point was perspective and political inertia, the political classes aren’t interested in the army and their takeaway from this will be that the British army is in great shape and that proxies can win wars, that Russia can’t advance more than two hundred miles and that NATO is getting even bigger. The problem, in their eyes, is probably solved.

As a caveat, I’d add that public opinion might actually weigh on this one for once, but I don’t think anyone is losing any sleep

There was an unhappy opinion floating around that the British army would at some point be handed a major defeat and only that would shake us of our hubristic complacency, I was of the opinion that the Ukrainian’s might end up taking that one for us. However, Russia’s military incompetence does seems genuinely staggering from top to bottom and I can’t see Russia as anything more than a spent force at this point, who’s he going to attack next? The Finns? Good look with that.

So, I think that the conflict actually complicates the identity crisis for the British army, as mainland powers adjust then the bulk of it becomes more removed from the Russia problem, it will need a new pacing threat to meet because this one is broken and it needs a capability yardstick to exceed (very much looking forward to the article by jedpc).

My hope therefor is that the army learns to live within its modest means and that it makes good choices.

Kind Regards and all IMHO,

Nemo

LikeLike

@Captain Nemo – thanks for your reply. Don’t know the outcome of Ukraine war yet, but Russia certainly strategically weakened for years, if not decades to come; perhaps permanently. Will this all prove an identity crisis for the British army? Maybe, maybe not. I expect the world will spend quite a while trying to work out the security implications of any new European security order, and the trick for the UK will be to identify its unique security offering and then the role the army plays in that. I suspect they’ll be some people still hankering after the old 1st Armoured and 3rd Mechanised Divs and who want the army designed to defeat a soon to be defeated adversary. I expect however that the reality is that we’ll see more of an acceleration in the implementation of Future Soldier rather than a modernised version of the structures of yesteryear.

LikeLike

What will be interesting to see is the autumn budget and the estimates for defense.

But from an army perspective what role does it have to play, and where does it play it? Head of IISS recently stated that the centre of gravity of European security has decisively moved to northern and eastern European neighborhood (possibly weakening EU defense ambitions even further in favour of NATO). Significant UK interests in forces that can have an enduring forward presence there, but also forces that can move quickly to NATO’s flanks. So perhaps we’ll see an interim adjustment to army’s future soldier prior to some more fundamental thought preceding a security and defense review by whoever wins the 2024 general election.

LikeLike