By Anthony G Williams

A second guest post by Anthony Williams, who is a highly respected UK writer on military small arms, automatic cannon and related subjects. Tony has been the Editor of IHS Jane’s Ammunition Handbook for 13 years and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of this field. He has written and co-authored several books on military guns and ammunition, given presentations to many conferences in the UK and USA, and maintains a website at http://quarryhs.co.uk .

Contents

01 – Introduction

02 – The Present situation

03 – The LSAT / CTSAS programme

04 – The calibre conundrum

05 – The armour problem

06 – The Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) programme

07 – Observations

01 – Introduction

The small arms of the US armed forces have been subjected to a continuous state of review for some years, in pursuit of the aim of replacing by 2025 the rifles and light machine guns (LMGs) which form the principal armament of infantry squads. Investigations into how to achieve this have taken the form of various parallel programmes. The most radical of these is the Lightweight Small Arms Technologies (LSAT) programme, which has been developing cased-telescoped (CT) ammunition along with new gun mechanisms to fire it. Other work has focused on identifying the optimum characteristics of the ammunition which would be used in the next generation of weapons (regardless of whether CT or conventional). In the meantime, the two families of weapons designed around the NATO calibres of 5.56 x 45 and 7.62 x 51 have been improved where feasible and supplied with more advanced ammunition to extract the final drops of performance from them. A further complication is that the US Marine Corps (USMC) has different views on some of these topics from the US Army, and the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) also goes its own way in selecting equipment. The Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) programme is intended to deliver replacements for existing weapons, with no preconditions concerning the nature of the weapons or ammunition.

02 – The present situation

At present the Army’s standard squad weapons are the 5.56 mm M4A1, a short-barrelled (368 mm) carbine, and the 5.56 mm M249 belt-fed light machine gun (LMG), a version of the FN Minimi. The 7.62 mm M240 general purpose machine gun (GPMG) and 7.62 mm M110 Semi-Automatic Sniper System (SASS) rifle may also be carried when required. In recent years, the ammunition has been improved with the NATO-standard 5.56 mm M855 gradually being replaced by the M855A1 and the 7.62 mm M80 similarly being replaced by the M80A1. The A1 designations mean that the full metal jacket (FMJ) bullets have been replaced by the EPR (Enhanced Performance Round) which contains no lead and has an exposed steel tip for improved penetration. New propellants have also been used, in the case of the 5.56 mm round to deliver the maximum practicable muzzle velocity from the short carbine barrel, at the cost of a rise in chamber pressure which is said to accelerate gun wear and shorten gun life.

The M249 LMG has always divided opinion with critics regarding it as too cumbersome and heavy for urban fighting but with too short an effective range for open country combat (it weighs about the same as the widely distributed Russian PKM LMG in the powerful 7.62 x 54R calibre, which has considerably greater range and effectiveness). The USMC has withdrawn most of their M249s from the squads, replacing them with the 5.56 mm M27 automatic rifle (AR), which is essentially a heavy-barrel variant of the Heckler & Koch HK 416 magazine-fed rifle. It is said to be more accurate, and capable of a higher level of sustained fire, than the M4A1, and is much lighter and handier than the M249. Furthermore, the Marines have expressed a wish to make the M27 their standard squad weapon in due course, replacing the M4A1 as well as the M249. This is a significant pointer to a possible future: a single weapon capable of sustaining a high level of automatic fire (albeit not as much as a belt-fed LMG with a quick-change barrel) as well as an accurate designated marksman rifle (DMR) while also being the standard squad carbine.

03 – The LSAT / CTSAS programme

During the early 2000s the US Army funded the LSAT development programme, with the initial aim of producing a belt-fed LMG matching the M249 in performance but halving the weight of the current gun and its ammunition. The AAI Corporation (now Textron) was the lead contractor for the project and responsible for the gun design. Both caseless and polymer-cased rounds were tried, with the polymer-cased one being selected for further development. Both were telescoped, i.e. the bullet was enclosed within the cylindrical case.The use of polymer for the case and also the belt links saved 41% of the weight compared with M855 ammunition belts: the total weight of a 200-round belt of ammunition was 1.76 kg compared with 2.84 kg for M855. Several LMGs were made and tested, but the Army was interested in more performance than the 5.56 mm calibre could offer.

This led to work on two larger rounds in the 2010s, in 6.5 mm and 7.62 mm calibre, with a name change – first to Cased Telescoped Systems (CTS) and then to Cased Telescoped Small Arms Systems (CTSAS), still under the design leadership of Textron. Both calibres use the same cylindrical case (52 mm long and 12.8 mm in diameter) to facilitate converting guns from one calibre to the other for comparison purposes – only a barrel change is needed. The 7.62 mm version was intended to match the 7.62 x 51 ballistics to act as a baseline, while the 6.5 mm calibre was selected as the optimum for its combination of good long-range ballistics with less weight and recoil than the 7.62 mm. The emphasis was again on an LMG, with a carbine using the same ammunition also receiving development funding. This work has been overtaken by the NGSW programme, in which CTSAS is participating (see below).

04 – The calibre conundrum

Ever since the 5.56 mm cartridge was introduced into US service in the 1960s, there have been criticisms of its lack of range and effectiveness. These became particularly vociferous during the fighting in Afghanistan, with engagements often conducted at distances well beyond the 300 metres which is widely considered to be the effective maximum for 5.56 mm NATO. As a result, 7.62 mm weapons were rapidly redeployed at squad level: the M240 GPMG and an updated version of the old M14 rifle. However, the guns and ammunition, while popular due to their performance, are heavy. Investigations therefore began into the optimum characteristics of a new round of ammunition for the next generation of weapons. This was reflected in a 2011 report from the US Army’s Program Executive Office Soldier: Soldier Battlefield Effectiveness. Some quotes from the text:

“A Soldier must be able to engage the threat he’s faced with – whether it’s at eight meters or 800.”

“To be effective in all scenarios, a Soldier needs to have true “general purpose” rounds in his weapon magazine that are accurate and effective against a wide range of targets.”

“Weapons….must be accurate and capable of engaging the enemy at overmatch distances.”

“Ultimately, Army service rifles must be general purpose in nature and embody a series of tradeoffs that balance optimum performance for a wide range of possible missions in a range of operating environments. With global missions taking Soldiers from islands to mountains and jungles to deserts, the Army can’t buy 1.1 million new service rifles every time it’s called upon to operate in a different environment.”

At the same time, the US Army’s Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center (ARDEC) was conducting trials of several different calibres between 5.56 mm and 7.62 mm. A range of performance metrics were set against weight and recoil, and the conclusions were that the optimum calibre for the next infantry rifle was between 6.35 mm and 6.8 mm. Shortly afterwards, the Army Marksmanship Unit (AMU), which carries out development and testing on behalf of the Army, also evaluated a number of cartridges before settling on two new designs, the .264 and .277 USA (6.5 x 47 and 6.8 x 47 respectively), which differ only in calibre. Not long after that, CTSAS concluded from their own research that 6.5 mm represented the ideal compromise, as mentioned above. Finally, SOCOM have been testing various weapons chambered for commercially available cartridges. They have been particularly impressed by the performance of the 6.5 mm Creedmoor round, originally intended for long-range target shooting. It has the advantage of being based on the 7.62 mm NATO cartridge so 7.62 mm guns can be modified to use it with little if anything more than a barrel change. It offers far better long-range performance than the 7.62 mm, but with only a small weight saving. The evolving requirements for NGSW now seem to be pushing the performance requirements even higher.

05 – The armour problem

A major concern of the Army is that body armour of considerable effectiveness has become widely available at a very low price. This has of course been worn by US infantry for decades but in future conflicts its use by adversaries must be anticipated. There are various levels of armour protection and different standards for measuring them, but the most common is the US National Institute of Justice (NIJ) scales, at the top of which is Level IV, which appears to be approximately equivalent to military armour. This will stop any current steel-cored armour-piercing rifle bullets of up to 7.62 mm NATO size and power. The least powerful steel-cored ammunition to have demonstrated that it can penetrate Level IV is the .300 Winchester Magnum used in US Army sniper rifles (7.62 x 67B); this is significantly bigger, heavier and more powerful than 7.62 mm NATO (over 5,000 J muzzle energy instead of c.3,400 J) and generates a lot more recoil.

Using tungsten-cored AP ammunition helps to improve penetration: the service 7.62 mm M993 can reliably penetrate Level IV, therefore so presumably will the 7.62 mm XM11158 Advanced Armor Piercing or ADVAP round intended to replace it (which is similar to the M80A1 except with a tungsten rather than steel penetrator). However, the equivalent 5.56 mm M995 cannot: in informal tests M995 sometimes penetrates Level IV when fired from a long barrel (560 mm), but that is nearly 200 mm longer than the M4A1’s barrel. Another option is to use a small-diameter tungsten bullet enclosed within a plastic sabot, or sleeve, which falls away at the muzzle, as developed by Winchester Olin and adopted for service in Swedish 7.62 mm sniper rifles. These achieve much higher muzzle velocities and penetration than conventional ammunition, but shot dispersion is greater. A problem with all of these solutions is that tungsten is a strategically important material with limited reserves, and is therefore both expensive and likely to become scarce in any major, prolonged conflict.

06 – The Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) programme

In 2013 the US Army announced a “Caliber Configuration Study” (CCS) to support two new small-arms programmes, designated CLAWS (Combat Lightweight Automatic Weapon System) and LDAM (Lightweight Dismounted Automatic Machinegun). Subsequently, CLAWS was replaced by NGSW (Next Generation Squad Weapon) and the CCS by SAAC (the Small Arms Ammunition Configuration study).

In the autumn of 2017 the Army started to talk in public about the results of the SAAC study, with the following key points:

- Calibre doesn’t matter much.

- Energy at the target does matter.

- Advanced bullet technology matters.

- Fire control matters.

Fire control, or hitting your target, had the largest impact. While weapon design and the use of advanced bullet technology will contribute heavily to the rifle of the future, how that weapon is aimed will change most radically. The Army envisages a digital display in a visor (so the rifle need not be held at shoulder height), wirelessly linked to a sight on the gun, and driven by a fire control system that calculates ballistics, windage and range, and could correct the aim when the shooter is off target. It would in effect be a miniaturised version of the systems used by armoured fighting vehicles and aircraft. It could potentially be set so that it would only fire when the gun was lined up with its target.

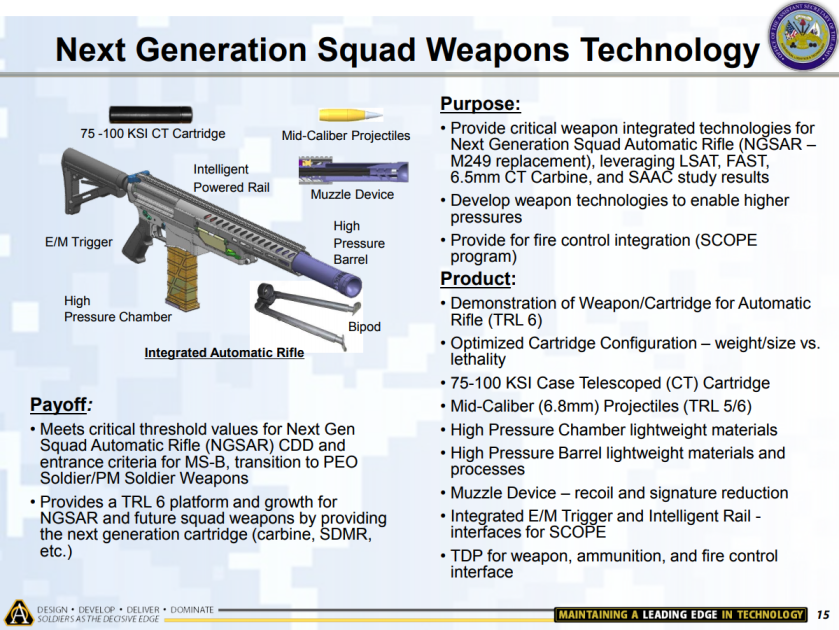

By February 2018 the Army was providing more information about a Next Generation Squad Automatic Rifle (NGSAR) — the first version in the Army’s NGWS intended to chamber a round between 6.5 mm and 6.8 mm — as a potential replacement for its 80,000 M249.

Of key significance was the revelation that the new round of ammunition around which the weapons are to be designed could generate a chamber pressure much higher than current weapons “to ensure that the rounds can still blast through enhanced enemy body armor at up to 600 metres”. This performance was expected to be achieved by using chamber pressures similar to those of a tank gun, i.e. up to 550 MPa (80,000 psi), instead of the usual 5.56 mm pressures of 380 MPa (55,000 psi) for the M855 and 420 MPa (60,000 psi) for the M855A1.

At that time, the NGSW programme consisted of three weapons: the NGSAR; a Next Generation Squad Carbine (NGSC); and a squad designated marksman rifle, along with specialised ammunition and a fire control system. Initially the Army had focused on fielding an improved carbine delivering range and accuracy superior to the standard M4, but the priority then switched to the NGSAR, with a target in-service date of 2022 rather than 2025.

Notional designs for NGSW weapons

In March 2018 the Army issued a draft Prototype Opportunity Notice (PON) for the NGSAR. This included the following summary of what the Army was looking for:

“The NGSAR is the planned replacement for the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) in Brigade Combat Teams (BCT). It will combine the firepower and range of a machine gun with the precision and ergonomics of a rifle, yielding capability improvements in accuracy, range, and lethality. The weapon will be lightweight and fire lightweight ammunition, improving Soldier mobility, survivability, and firing accuracy. Soldiers will employ the NGSAR against close and extended range targets in all terrains and conditions. The NGSAR support concept will be consistent and comparable to the M249 SAW involving the Army two-level field and sustainment maintenance system.”

More detailed requirements were as follows (final version):

- Weapon weight (weapon, sling, bipod, suppressor, no magazine/pouch): 12 pounds (5.4 kg) or less

- Ammunition Weight (no magazine, belt, belt components, box, or feed systems): 20 percent less than an equal brass case weight volume

- Dispersion Semi-Automatic: 7 inch (18 cm) Average Mean Radius 400 meters; Automatic: 14 inch (36 cm) Average Mean Radius 400 meters

- Weapon Length (with buttstock extended): 35 inches (890 mm) or less

- Fire Control (includes day/night optics): 3 pounds (1.36 kg) or less

- Lethality Requirements: (restricted distribution – not publicly available)

- Rate of Fire: 60 rounds per minute for 15 minutes without a barrel change or cook-off

- Suppressor: Flash 80 percent less than unsuppressed M249; Acoustic 140 decibels or less

- Weapon Controllability: Soldier firing standing with optic at a 50 metre E-Type silhouette given 3 to 5 round burst must be able to engage in 2-4 seconds placing two rounds 70 percent of the time on target

In June 2108, it was revealed that ten initial bidders had been reduced to six as follows:

Aircraft Armaments, Inc; Textron (AAI Textron – USA)

PCP Tactical (a division of PCP Ammunition, USA)

SIG Sauer (a Division of L&O Holding, Germany)

General Dynamics Ordnance & Tactical Systems (GT-OTS, USA)

FN America* (Part of FN Herstal, Belgium)

(FN has been permitted to make two submissions described as Lightweight and Adaptive options).

In July 2018, an update from the US Army Contracting Command, announcing the award of six separate Fixed Priced, Full and Open Competition prototype Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs). These prototype OTAs were for the manufacture and development of a Next Generation Squad Automatic Rifle system demonstrator representative of a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 6 and Manufacturing Readiness Level (MRL) 6. The demonstrators were to be ready by June 2019 for the first phase of practical testing.

In October this year a new draft PON was issued by the US Army. The designation reverted to NGSW, covering two weapons: NGSW-R (Rifle), the planned replacement for the M4/M4A1 carbine, and NGSW-AR (Automatic Rifle) to replace the M249 LMG. To quote the PON:

“NGSW-R” refers to a prototype 6.8 millimeter rifle with sling, flash hider, suppressor, cleaning kit, flash hider/suppressor removal tool, and quantities of magazines required to provide a minimum of 210 stowed rounds.

“NGSW-AR” refers to a prototype 6.8 millimeter automatic rifle with bi-pod, sling, flash hider, suppressor, cleaning kit, flash hider/suppressor removal tool, and quantities of magazines/drums/belts/other required to provide a minimum of 210 stowed rounds.

The new draft PON states:

“The Government is seeking Industry questions and comments to assist in shaping the NGSW program strategy to rapidly develop and deliver prototype weapons and ammunition. The intent is to engage Industry early in order to provide the best materiel solution for the NGSW program.”

The need for the contestants to design their own cartridge around a government-provided 6.8 mm General Purpose bullet (designated XM1186) is stated, subject to performance requirements (information about which is still restricted). Both the R and AR are to use the same ammunition.

The following list of requirements is included (covering both weapons) but curiously, gun weight and length are not specified:

- allow for ambidextrous operation and controls;

b. include a removable flash hider, suppressor, and a tool for removal after firing or for maintenance;

c. include a tactical carrying sling with quick release attachments;

d. include selection positions for Safe, Semi-Automatic Firing, and Automatic Firing

modes;

e. be resistant to corrosion, abrasion, impact and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense (CBRNE) contaminants, decontaminants, battlefield-chemicals,

electromagnetic pulse and cyber-attacks;

f. reduce visual detection via a neutral non-reflective, non-black color not lighter than

Light Coyote 481 and not darker than Coyote 499;

g. function in all environments and weather conditions, including marine, high

humidity, rain, and desert conditions;

h. be compatible with combat clothing (including body armor and Modular Lightweight

Load-carrying Equipment), CBRNE, wet weather, and cold weather gear;

i. provide interchangeable magazines between both weapons if NGSW-AR utilizes a

magazine; and

j. include MIL-STD-1913 equivalent rails capable of mounting Rifle Combat Optic,

Close Combat Optic, Aiming Laser, Family of Weapon Sights–Individual, Squad-Fire

Control and other legacy enablers.

A definitive PON is expected in the next couple of months.

08 – Observations

While the sights and fire control system are rightly identified as the key technical innovation in improving effectiveness, not a lot has been said about them. Their development is of course going on in parallel with the work on the gun and ammunition, and is effectively independent of it. Whatever squad weapons are chosen, any new sights will be usable on them via the standard accessory rail systems, needing only appropriate software to match the ballistics. The main question will be how many features the Army wishes to include.

A laser rangefinder coupled to a ballistic computer which presents the appropriate aiming mark in the sights is a given (it can already be bought off the shelf, commercially). Probable add-ons include: night vision (although given its bulk this could be a separate addition, as it is now), automatic identification of people (some smart-phone cameras can do this), and restrictions on firing unless the gun is aimed accurately. Apart from wind drift (the toughest problem), solutions to the other sensor requirements do not seem to pose any technical difficulties, but the more of them that are packed into the system, the bigger, heavier and more costly it is likely to be.

The main observation concerning sights is that the principal problem faced by infantry in medium/long range fire fights is not in hitting their targets but in identifying their location; a problem which is likely to worsen given the increasing use of suppressors. Much small-arms fire is merely in the general direction that the soldiers think enemy fire is coming from, in the hope of keeping their heads down. Stopping the gun from firing unless it is on target would prevent any such suppressive fire, so may in practice be a little used feature.

The focus of NGSW so far has been mainly on the guns and ammunition, although given the restrictions on revealing the performance requirements, not a lot has been said in public about the ammunition. All that is known is that the cartridge must be of 6.8 mm calibre, must use the Army’s own General Purpose bullet, must be fired at a sufficient velocity to have a body armour-defeating performance at up to 600 metres, can utilise very high chamber pressures, and must show weight savings of 20% over equivalent brass-cased ammunition. The ammunition is the key to the gun, so will be commented on first.

The 6.8 mm General Purpose bullet is understood to be an EPR type with an exposed steel tip, weighing 8.1 to 8.4 g (125 to 130 grains). To meet the 20% weight saving requirement with a conventional round would require something other than an all-brass case. Polymer with a metal base is the most popular approach, with several makers achieving overall weight savings in the 20-27% range depending on the proportion and type of metal reinforcement to the base (necessary to prevent the extractor claw from ripping through a polymer rim). However, bimetallic cases (initially steel and light alloy) are in commercial production and also achieving 20+% weight savings. The CT cases used by Textron have the advantage of being able to use push-through loading and ejection, without any high stress areas such as rims, so require no metal reinforcements and can accordingly achieve weight savings of more than 33%. In belt-fed guns they can also use polymer links, pushing the weight savings up to around 40%. No small-arms cases (conventional or otherwise) have been expected to work at 550 MPa chamber pressure, however, so in terms of technology that is in unknown territory and will require exhaustive development and testing.

The key issue is the muzzle velocity (MV) at which the bullet needs to be propelled, as this will partly determine the quantity of propellant required and therefore the size and weight of the cartridge case. “Partly” because another factor is the barrel length: the shorter the barrel, the more rapidly the bullet needs to be accelerated to reach the MV. This means that, for any given MV, there is an inverse relationship between the cartridge power and size, and the barrel length. If the intention is to push the muzzle velocity to the extremes suggested below, that will be much easier to achieve with a long barrel, but to keep the gun within the overall length limit (likely to be set in the definitive PON), that means a bullpup layout will probably be required.

The performance requirements are still confidential, but a muzzle velocity of up to 1,070 m/s (3,500 fps) is rumoured. With an 8.1 to 8.4 g bullet, this would develop a muzzle energy of 4,600 to 4,800 J – almost as much as the .300 Winchester Magnum sniper round which is designed to be used in a long barrel. Both gun and ammunition would be large and heavy, and the recoil would make achieving controllable rapid (let alone automatic) fire very difficult. The Army is going to have to decide whether the consequences of achieving their long-range armour penetration target make that worthwhile, in the light of these problems plus the considerable technical risk involved in pushing a small-arms system to operate at such unprecedentedly high pressures and (inevitably) temperatures.

A separate issue concerns the nature of the Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW); a generic functional term which can apply to both ARs and LMGs, the choice between which is left open in the PONs. To give a simple comparison, the AR is basically a magazine-fed rifle with a fixed (but heavier) barrel. The barrel thickness can absorb more heat than the carbine, permitting a higher sustained rate of fire. Open-bolt firing could allow quicker cooling between bursts, but tends not to be provided because it would require different handling from the rifle; undesirable in the stress of combat. Another problem faced by the AR is its limited ammunition capacity; with a conventional double-column box magazine the relatively fat cases would probably limit capacity to little more than 20 rounds; quad-stack magazines have been developed but have so far not been accepted by the Army. Neither have drum magazines, which are bulky and heavy, and an inconvenient shape for carrying. On the other hand, it is convenient for the AR to use the same magazines as the carbine.

In contrast, a typical LMG is belt-fed, fires from an open bolt and has a quick-change barrel, all of which considerably boost the sustained rate of fire. These features, plus a sturdy bipod and the extra ruggedness required to tolerate extensive automatic fire without being shaken to pieces, result in a bulkier and heavier weapon. In practice, barrel-swapping seems to be rarely practiced in combat as carrying a spare means even more weight. So critics of the LMG concept generally argue that its features are best applied to a more powerful support weapon which would generally be mounted on a tripod or vehicle for maximum stability, accuracy and range: such as the Lightweight Medium Machine Gun in .338 Norma Magnum calibre, which rivals the long-range anti-personnel effectiveness of the .50 (12.7 mm) heavy machine gun.

A cynic might observe that there appears to be an element of fashion in the AR vs LMG debate; those who currently have LMGs view the handiness of the AR with envy; those with ARs may wish for the sustained rate of fire of an LMG once they get into intensive close combat.

Conclusion

Armies rarely get the opportunity to select “clean sheet” small arms, unconstrained by being tied to using legacy ammunition or gun designs. It is understandable that they wish to make the most of this by adopting leap-ahead systems which offer the promise of world-beating performance now, and long effective lives. Unfortunately this approach carries considerable technical risk, which past experience indicates greatly multiplies the probability of the programme running behind schedule and over budget, and ultimately being cancelled.

The last time the US Army tried such a revolutionary approach to new small arms was the Special Purpose Infantry Weapon (SPIW) programme of the 1960s; a rifle designed to fire bursts of high-velocity flechettes (and later, with a repeating grenade launcher built in as well). Despite development proceeding for about a decade, the technical issues proved insurmountable and the project failed, leaving the “interim” 5.56 mm M16 to become the Army’s new rifle by default.

The main feature of the NGSW programme is the extreme performance requirement driven by the wish to defeat body armour at extended range. However, in the long term that may be an unachievable vision. History is full of escalating weapon vs armour contests, and body armour hasn’t stopped developing. It would not be surprising, should the Army actually get its NGSW super-velocity rifle, to find that within a few years, armour capable of defeating it is introduced. And then what? Looking further into the future, the powered exoskeletons currently being developed may make it easier to carry a lot more weight – including heavier armour.

How to deal with body armour is a genuine issue which has been ignored for too long and needs addressing, but adopting a magnum-class super-velocity rifle, even if it is technically successful, might prove to be the wrong answer in the long run. While it is impossible to be sure of future requirements, it may remain the case that body armour is little used by most adversaries, for whom a very high-performance round would be overkill. A 6.8 mm round generating nearly 5,000 J muzzle energy would unquestionably be an excellent penetrator even with a steel-cored bullet – possibly too much so in many scenarios, since the risk of collateral damage due to over-penetration would be high, especially in urban areas.

So what should the Army do? It is a good idea to develop a single round with the long-range performance to replace the 7.62 mm as well as the 5.56 mm, and the key to achieving this is indeed to select a calibre in the region of 6.5 mm together with a low-drag bullet which loses velocity and energy as slowly as possible. Setting a lower performance requirement (but still high enough to be a significant improvement on current weapons) would result in a smaller and lighter cartridge operating at a lower pressure and developing less heat and recoil – plus lighter and more controllable weapons to use it. This should also enable existing 7.62 mm weapons to be adapted to fire a conventional version of the cartridge (evaluated in both brass-cased and lightweight versions) as a fall-back in case the CTSAS proves unacceptable.

The body armour problem may be best addressed by using specialised projectiles. There will obviously be an ADVAP version of the 6.8 mm bullet; should this later prove inadequate, then saboted penetrators are worth re-examining. One way to reduce the cost of the tungsten-cored rounds may be indicated by the development by Nammo of bimetal cores, mainly steel with a tungsten tip, which give penetration intermediate between the steel and tungsten types.

Another option is to develop two performance levels: one using the GP bullet fired at standard pressures, the other firing AP bullets at much higher pressures and velocities. The guns would have to be designed to handle both types without manual adjustment to the operating system.

Finally, given the importance of the NGSW programme, not just to the USA but potentially to the rest of NATO, it is important for any prospective system to be thoroughly tested for an extended period by the users. When the prototype developed by Mikhail Kalashnikov’s team won the 1947 Soviet competition for an assault rifle, it was made in some numbers as the AK-47 and issued to ordinary infantry units to use for a period of two years. As a result of the exhaustive evaluation which followed this period, numerous changes were made before the weapon was formally adopted in 1949 as the AK. The gun’s reputation speaks for the success of this approach. In particular, if the CTSAS is favoured, then given the higher risk which always accompanies advanced technology, simultaneous evaluation of both this system and a conventional alternative is advisable before a final decision is made.

Key points

- The combination of unprecedentedly high operating pressures with new technologies in ammunition materials and (in the case of the CTSAS) ammunition and gun design, poses a high risk of project failure.

- The high performance indicated is likely to develop excessive recoil, gun heating, and overpenetration against unarmoured targets.

- Very high velocities would enable the penetration of current levels of body armour but these can be expected to evolve.

- The possibility of using standard pressures and velocities for GP ammunition and higher performance for the AP rounds could be considered.

- Saboted AP ammunition could be considered.

- Tungsten is an expensive material, so a bimetal (steel + tungsten) cores could be considered.

- Testing and evaluation of the leading contenders should be exhaustive before a final decision.

*********************************************************************

Excellent article, still digesting it but would like to request one small clarification.

In:

“The need for the contestants to design their own cartridge around a government-provided 6.5 mm General Purpose bullet (designated XM1186) is stated, subject to performance requirements (information about which is still restricted). Both the R and AR are to use the same ammunition.”

should that be 6.8mm vice 6.5mm?

LikeLike

Well spotted. Yes, it should be 6.8 mm. Having said that, per Tony’s conclusions, the specifications for NGSW ammunition seem so extreme that I wonder if they won’t be scaled back? My view is that a 7 gram 6.5 mm projectile fired at 950 metres per second would comfortably outperform 7.62 mm NATO. The need to penetrate Level IV body armour is taking us into Winchester magnum territory. This can only increase weight and recoil issues. I guess that when prototype weapons fail to fully meet the requirements, they’ll be adjusted.

LikeLike

As stated in other lines of communication, I too wonder about the change to 6.8 when the current commercial 6.5 Creedmoor is so close to what they want and so would appear to be a logical starting point for evolutionary/spiral development.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A Soldier must be able to engage the threat he’s faced with – whether it’s at eight meters or 800.”

That’s primitive bollocks, and also at the heart of the problem.

The tactical idiocy of shooting at targets that far with infantry weapons other than sniper rifles leads to excessive weights of equipment and is generally incompatible with intelligence, literally.

Infantry that does see hostiles so far out (and can identify them as such, which is highly questionable) should observe, report and watch them die to support fires or be content believing that command will make good use of the intelligence for manoeuvring.

Only idiots give their position away from so far by shooting and wasting their munitions.

Infantry that can see competent hostile infantry past 100 m distance is employed in the wrong kind of terrain. Competent infantry vs. competent infantry will be firefights at less than 100 m in the terrain where infantry rather than artillery or armour are the main forces.

Infantry fires at longer distances are treacherous and wasteful harassing fires and possible against stupid OPFOR only.

Discussions on infantry armament and ranges are almost always way too focused on hardware and stupid small war harassing fires. They’re also often driven by primitive ‘I have to fight back’ impulses that are incompatible with intelligent tactics.

https://defense-and-freedom.blogspot.com/2009/07/infantry-combat-ranges.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that 800m is too far for regular infantry weapons, but understand what the speaker is trying to say. You need a round that is effective over whatever range that is deemed appropriate for regular infantry weapons be it 200, 300, 500, 600m. It does you no good to have a round that’s great out to 50m but trash beyond that nor does it do you any good to have a round that reaches out to 1km but ineffective at close ranges due to only being able to have 5 in your magazine. Granted extreme examples but I think they get the point across. What is the “perfect” infantry range? IMO out to 600m with current rounds/technology though I reserve the right to alter my opinion in the future as technology progresses.

LikeLike

During the Afghanistan conflict, the Taleban regularly engaged ISAF units at ranges of 600-900 metres precisely because they knew that ISAF 5.56 mm weapons couldn’t hit back. Using Russian made SVDs and PKMs firing the 7.62x54R cartridge, enemy fire was not pinpoint accurate, but dangerous enough to suppress. Sometimes it could force a withdrawal into an IED kill zone or allow the Taleban to manoeuvre into an assault position. The response was the widespread re-adoption of 7.62×51 mm NATO weapons and ammunition. Designated sharpshooters using x6 scopes were frequently able to hit targets at 800 metres. Add the latest smart gun sights that combine laser rangefinders with ballistic computers, and effective long range shooting has become much less difficult. The trouble with 7.62×51 mm is it has too much power at shorter ranges. A less powerful, but more aerodynamic cartridge, such as the 6.5 mm Creedmoor, starts off with less energy, but overtakes 7.62 mm at longer distances through its greater efficiency. It’s a clever solution and is working very well for SOCOM in both rifles and machine guns. The problem with the US Army’s new 6.8 bullet and any cartridge built around it is not range, but the requirement to penetrate Level IV body armour. A less powerful, but highly efficient 6 mm, 6.35 mm or 6.5 mm round weighing 6-7 grams (100-115 grains) would overcome 5.56 mm deficiencies without imposing weight and recoil issues that are more substantial than 7.62 mm.

LikeLike

Perhaps I was not clear enough in my earlier response. Allow me to clarify. I do not believe general infantry need to train to be able to hit man sized targets at 800m, for me that limit is 500 or 600m but that does not mean I think that the round they use should not be able to reach out to 800m or more. It would be the job of the DM to effectively engage targets beyond the 600m though the rest of the squad would be able to effectively suppress to the same ranges the DM can engage. Some of that suppression would result in kills as a result of either skill or probability. In my opinion, 6.5 Creedmoor is a round that has that capability and can be used in the standard rifle/carbine, DMR, SAW, and infantry carried MMG. For vehicle/emplaced MMG I’d go for .338NM but that’s a discussion for a different article.

LikeLike

Infantry needs at the very least concealment to be effective. It’s mere targets without concealment.

The ability to extricate yourself from trouble should be sought in smoke rather than firepower – you cannot suppress everyone anyway.

So infantry is suitable for employment in concealment-rich terrain, and can have observation posts at the edges of such terrain to control open (long line of sight) areas. This observation may lead to occasional long range shots (particularly with missiles), but it would mostly be about security, reporting and calls for support fires.

Back in the Cold War the infantry needed about 300 m effective range because art was dispersing so much it couldn’t provide more close fire support. Nowadays we could do with less, maybe 200 m.

The ordinary infantry small arms need no more than 100…300 m effective range (the essential effects would mostly happen at less than 100 m regardless of terrain). Some weapons (‘bazooka’, battalion snipers, dedicated anti-MBT hardware) need more range, but 600 m would usually suffice (safe for ATGMs, which could easily exploit 2 km because their targets are more easily spotted).

A long time ago I advocated two intermediate calibres; something between 5.56 and 7.62 for dismounted use and something between 7.62NATO and .50BMG for mounted use and snipers.

I gave up on the former because of weight considerations. Let’s stick to lightweight cartridges (and carbines, LMGs). We can still move to .338 if powered and fully NIJ level 4 protected exoskeletons appear.

—————

Last but not least a German observation from WW2; attacks that failed did typically fail at 400+ m distance to the line of defence not because of rifle and machinegun fire, but because of indirect fire support. Artillery fires into marshalling areas were commonly more deadly than artillery support fires against troops in contact. Infantry fires add some attrition, but don’t win any battles.

The lesson shouldn’t be to try increase infantry fires, but to try reduce infantry susceptibility to arty fires. This requires the ability to break contact and move quickly, and heavy armament doesn’t help this at all.

LikeLike

“During the Afghanistan conflict, the Taleban regularly engaged ISAF units at ranges of 600-900 metres precisely because they knew that ISAF 5.56 mm weapons couldn’t hit back.”

Extremely often referenced, and irrelevant. Those were harassing fires. Take cover, break contact. Or even better; kick several levels of idiot superiors into unemployment for not providing sufficient overwatch and smoke capabilities for daytime ops.

Look at how extremely overburdened Western infantry regularly was in AFG. To blame their rifles’ effective ranges for the tactical troubles is nonsense. They should have had ATVs in lowlands, and several overwatch positions (20 mm autocannons or 76…105 mm guns brought into high position by helo) and mortar support in mountains. They could also have had support by Cessna piston engine aircraft with gimballed thermal/CCD sensor/SAL and tiny HE glide bombs – but Western land forces bureaucracies were too inflexible and insisted on attack helicopters and jets.

Hiking in mountains is exhausting with mere clothes, tarp, sleeping bag, mattress, food and a little water. Radios, batteries, 5.56 guns and 5.56 munitions add a lot of pain to feet and back and slow you down. To add even further weight makes everything ridiculously sluggish even for acclimatized men and makes them incapable of achieving anything. Patrolling is a mere means to an end, except when it’s useless.

You have to look at firepower as a part of all the means towards the desirable end state. It makes no sense to look at firepower for a month, then look at infantry’s burdens for a month, then look at infantry body armour for a month et cetera.

Professional decisionmakers get paid to make tough decisions (compromises), not to pursue one partial maximization after another, leaving behind a dysfunctional mess.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The main problem is imo, that armies in this area try to solve different tasks with the same system. Because the task to fire on enemy infantry up to 100 m and on the other side up to 800 m is so different, different and therefore more specialised weapons are here much better than an One-fits-it-All Assault Rifle (the overall concept of the assault rifle is even very questionable).

Instead of givinig infantry assault rifles one could think of ultralight PDW like weapons for short distances (which would still defeat body armour at close distance), especially for close combat and immediate self defence this would be even an advantage (more ammunition, shorter, lighter, no recoil etc etc) and then one could invest the spared weight (of the not used AR) in more support / specialised weapons for the infantry unit.

Such a unit could have signifikant more machine guns in calibres like the .338 norma mag, more sniper rifles, more grenade launchers etc and with this weapon mix much more firepower also over greater distances. And for the short distances it could have much more grenade weapons of all kind which are more effektive against enemy infantry than bullets.

Some kind of bullpup grenade rifles (from seizure, weight and appearence like the XM 25) could be here the solution as additional weapons in the group / squad / platoon whatsoever to defeat enemy infantry and also to defeat armour because dedicated armour piercing grenades in this caliber offer much more potential than simple conventional ammunition.

LikeLike

I am with @lastdingo on this one. The response to Soviet 7.62 in the hands of Taliban in AFG was the correct one, more 7.62×51 NATO MG and DMR . Could we have done with a 7.62 MG than the L7, sure. Could we do with lighter ammo, for sure, bring on the bi-metal or polymer cases.

Now @lastdingo is mostly talking about infantry combat in peer-to-peer all out war scenarios, which is not congruent to COIN where ROE stops you dropping a ton of 155mm HE on every team of four flip-flop wearing insurgents. However as noted above, our response to the mountain ridge to mountain ridge COIN issue was probably the right one. Meanwhile what about all the words written about lowering the weight burden on the average infantryman ?

So does the single intermediary cartridge, with its suggested logistics improvement of replacing both 5.56 and 7.62 within the section really pay off, if it brings added weight and complexity (rifle fire control system ? What could possibly go wrong with that……).

I remember years ago Tony wrote an article on shooting the CBJ 6.5mm cartridge with it’s 4mm sabot encased tungsten armour penetrating bullet from a converted 9mm B&T machine pistol. According to the test data on their website, it has pretty impressive armour piercing capability, perhaps good enough for members of the squad who are not carrying a belt fed MG, or a DMR or a six round 40mm grenade launcher ! Effective to 300m, good enough for personal defence and assaulting through the objective ???

LikeLike

With 6.5 CM I see it close to a zero sum gain for the squad as a whole because the weight gained by the 5.56 rifleman is lost by the 7.62 machine gunner and 7.62 DM. Items can be shifted around within the squad to get back to pre-conversion individual weights if so desired. Maybe my view is too simplistic.

LikeLike

Why not have 1 or 2 designated marksman per squad/section with adequate training, full power rifles in a proper lone range caliber (7.62 NATO is mediocre, something between 6.5 Creedmoor and .338 Lapua), armor piercing bullets and fancy sights/fire controls instead of adding a ton of weight, complexity and cost to every soldier? Most of them won’t get the training to use those systems anyway.

Add a Carl Gustaf or a lightweight mortar and you have sufficient long range firepower.

LikeLike

The “we need to be able to shoot back” thing isn’t about military utility. It’s about psychological needs and desires. They hate the idea of being unable to punch back for a while, regardless how much the organisation they’re in is capable of hammering the harassers.

Besides, the equipment you’ve mentioned is really heavy, too heavy for squad level. A single CG per platoon is borderline too heavy (the munitions are the problem).

LikeLike

Logistically it’s better to have a single caliber that the entire squad uses from standard rifleman to DM to MG as it makes things much simpler. if something like 6.5 CM were used as the “squad round” even sniper could use it for all but the most extreme ranges or hardened of targets. From a logistics standpoint it easier to track and store a very large quantity of a single caliber than it is large quantities of two calibers (Note I am not including specialist sniper calibers). It drastically reduces the chance of resupplying a unit with either incorrect quantities or types of ammo. Granted with a single caliber you can still get the quantities wrong but at least you don’t have the chance of getting resupplied with 1000 7.62 when what you needed was 5.56.

LikeLike

I agree; 6.5 mm Creedmoor is in many ways an ideal calibre. Compared to 7.62 mm, it has a lower weight, lower recoil, flatter trajectory, shorter flight time, is less prone to wind drift, has greater retained energy beyond 300 metres, and increases hit probability. It uses a necked-down 7.62mm case, which makes re-chambering 7.62 mm weapons easy. But it’s probably more powerful than strictly necessary in a weapon that’s heavier than it needs to be. The same projectile packaged in a slightly smaller cartridge (like a 47 mm Grendel case) and made from polymer would be only marginally heavier than 5.56 mm. Even so, still a lot to like about the 6.5 mm Creedmoor, not least because it fixes everything that’s wrong with 7.62 mm and genuinely enables a single calibre to be carried at squad level.

LikeLike

I think it all gets back to whether having the capability to reach out to 1k m is important or not. If not, and 600m or so is sufficient then Grendel is the way to go but if it is then Creedmoor is the answer. I err on the side of having the capability to go out to 1k, as evidenced by my responses here and in other discussions, but that is my own person opinion based on my ingrained Marine marksmanship philosophy. That is not to say my opinion is the right answer for the Army (I am aware it may not be), only how I would solve it were it up to me. As long as the Army can find/decide on a single caliber with the “positive” characteristics, we have discussed (and allowable by physics) then I’d count it as a win whether it’s 6, 6.5, 6.8, 7 or whatever.

LikeLike

It’s not accurate to say that logistics would be simplified by using a single caliber. In the US we use a DODIC which is a four digit identifier for different types of ammunition. A typical unit is going to have a bunch of DODICs (5.56 on clips, 5.56 on links, 7.62 in boxes, 7.62 on links, 9mm, LAW rocket, 40MM grenades in three flavors, CG rounds in several flavors, hand grenades, 12.7 ammunition, 60MM, 81MM and 120MM mortars in HE, MAPAM, WP, Illum, IR Illum, etc).

Even if you used one caliber for all rifles and MGs you’d cut exactly one DODIC from over a dozen.

LikeLike

If both rifles and MGs use a common caliber I’d argue it’s more just replacing a single DODIC. Logistics is more than just identifier numbers. Logistics is more than just an identifier number. It’s the whole ball of wax from procurement, to training, to maintenance, to use….

If a single caliber is used, more rounds will be bought which will drive down the individual price of each round due to economies of scale, maintenance wise instead of needing have a set of specific tools for each caliber a common tool set could be used. For example instead of a 5.56 and a 7.62 set you could have 2 6.8 sets and get a discount on the second set due to buying more than 1. Yes the examples are simplified but they still illustrate the effect a single caliber could potentially have on logistics.

LikeLike

RE:

“6.5 mm Creedmoor is in many ways an ideal calibre. Compared to 7.62 mm, it has a lower weight, lower recoil,

[…]

Even so, still a lot to like about the 6.5 mm Creedmoor, not least because it fixes everything that’s wrong with 7.62 mm and genuinely enables a single calibre to be carried at squad level. ”

The funny thing is that the Swedish army had gone for * such round, from rifles to MGs* , with their:

” Swedish military wanted to change from * [long-shaped bullet]6.5×55 mm* to the NATO standard: 7.62 x 51 mm NATO.

One British general who visited Sweden said: Why do you want to change from 6.5×55 mm to 7.62 NATO? The old Swedish 6.5×55 is much better and there is no need for you to change! ”

– I feel another change coming on… in 15-20 years’ time, though

LikeLiked by 1 person

In this article the US Army appears to have decided on a 6.8mm round. But in the article on the USAOC the same Army appears to be considering the 6.5mm round. What can we expect? That the whole US will eventually decide on one or another, or something in between? (and eventually take the rest of NATO with it). Or are they looking at one round for the bulk of the army and a separate round for special forces?

LikeLike

US RDECOM has developed a number of new small arms projectiles based on the EPR design and other technologies. Most have an exposed steel tips to aid penetration and are designed to fragment to aid energy transfer into a target. Such projectiles are known to exist in 6mm, 6.35mm, 6.5mm, 6.8mm and 7mm. Both the 6.5mm and 6.8mm could easily be incorporated into a necked-down 7.62mm case – like 6.5mm Creedmoor. One school

of thought is that the range and terminal effect of a 6.5mm or 6.8mm cartridge would be way in excess of what is actually needed. In fact, a 6mm or 6.35mm cartridge could easily deliver 600 metre lethality in a package that’s very close to existing 5.56 mm size and weight. It’s hard to know what is the optimal solution for use at squad level until proper tests have been carried out. When trials deliver reliable data, we’ll be able to make informed choices about next generation options, but NGSW is still far from being decided let alone being a done deal.

LikeLike

As for “Most have an exposed steel tips to aid penetration” that is what Russia has been doing for a long time (exactly for body armour reasons). At least since, in their own words “they stepped on the same rake (as us) by going for too small a calibre, because most contact was supposed to be between AI dismounting and suppression, rather than hitting a target at distance, was the key.

However, as for ” In fact, a 6mm or 6.35mm cartridge could easily deliver 600 metre lethality in a package that’s very close to existing 5.56 mm size and weight. ” that misses the point about “the optimal solution for use at squad level ” as you will need to consider the DM and SAW-like requirements – this time around, not patching up by putting in higher calibre MGs when the combo is found wanting.

LikeLike

history repeats?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.280_British

LikeLike

I suspect that from the technical point of view, the .276 Enfield would make a closer comparison: this was a magnum-class cartridge developed after the Boer War to allow British soldiers to out-range any opposition. It had a lot of problems concerning recoil, muzzle flash and blast, barrel heating and wear, and I suspect that the army was relieved when WW1 caused the project to be cancelled: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.276_Enfield

LikeLike

Does not the CT ammo technology add a new dimension to the weight debate?

If you can get 6.5 capability for the same or less weight than the current 5.56

Also, using the same external shaped ammo for 5.56 capability when range is definitely not an issue (Urban, jungle etc) then it seems something to consider.

“Thus one’s victories in battle cannot be repeated, they take their form in response to

inexhaustibly changing circumstances.” Sun-tzu (fourth century B.C.)

LikeLike

Yes, the weight saving is an important factor, but the very powerful 6.8 mm round proposed would still suffer from recoil and barrel heating issues.

LikeLike

And then there is the body armour defeating armour piercing requirement, and the use of Tungsten (which is why I had liked the CBJ Tech ammo) :

https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2017/10/29/level-iv-unbeatable-armor-caliber-problem-tungsten/

Would a sabot round with a steel core be able to penetrate Level IV but at closer range? back to 300 to 400m lethality for the individual weapon, and retain a separate caliber for MG and DMR – it’s not like we have not been able to live with the situation through over a 100 years of conflict ?

If supersonic .300 Blackout from a 9 inch barrel is rated as “combat effective” at just over 400m, then would a CBJ Tech sabot round with a hardened steel bullet instead of Tungsten be able to penetrate Level IV plates at 400m ? Their Tungsten round is advertised as beating NATO CRISAT target including titanium plate and kevlar to 1200m ………

LikeLike