Nicholas Drummond

On 25 October 2018, the UK Secretary of State for Defence, the Rt. Hon. Gavin Williamson MP, announced that the British Army would open all combat roles to women. This includes serving in UK Special Forces as well as in Infantry and Armoured regiments.

The decision has generally been welcomed by male and female soldiers, officers and enlisted ranks, who see it as a positive step that will increase the Army’s effectiveness by enlarging the pool of candidates from which it can draw recruits. The initiative also recognises the contribution and commitment made by female soldiers since they were first allowed to perform non-combat support roles.

The idea of extending female integration to include women fighting in combat roles is not something that appeals to everyone. A small, but vocal contingent of serving and retired male soldiers (as well as a few women) has expressed genuine concern. It would be easy (and unfair) to dismiss their point of view as being purely misogynistic or outdated; but since many are seasoned professionals whose objections are based on their own combat experience, their perspectives deserve objective consideration. Therefore, the aim of this article is to provide a balanced discussion of the component issues for and against women on the frontline.

A prevailing view among doubters is that gender equality in the Army is a Government sop for the sake of political correctness. If it is necessary for the Army to reflect the changing nature of UK society, it must balance female roles in the Army with practical considerations that reflect the very real differences between the sexes that limit what women can and cannot do. The counter view of those who endorse women in combat roles is that the Army should reflect the society it serves, because it will better embody British values, our culture and our national character. Both points of view are valid, but who is best positioned to decide what roles women should or shouldn’t do, men or women?

Since suffragettes first campaigned for the right to vote, women have sought to achieve equality with men. They wanted the same pay for doing the same work. They didn’t want to be penalised for having children. They didn’t want entry standards for any occupation or job to be lowered to allow them in. They simply wanted parity and fairness. Given how every other walk of life now affords women the same opportunities as men – so long as they possess the necessary professional qualifications – is it not right that the Army should also do the same? For example, if a female soldier can meet the entry requirements, complete the necessary training, pass the qualifying tests, and achieve higher standards than her male counterparts in the process, then why should she not be allowed to become a helicopter pilot, a sniper, or special forces operator? Conceptually, should there be a barrier that prohibits any women who meets the required standards from serving in whatever capacity she wishes?

The proponents of all-male combat units cite six reasons why women should not serve in combat units:

- Human Physiology and Physical Fitness

Belief: It is a biological fact that women are generally physically smaller than men, with less bone mass and less muscle density. Female body chemistry makes it harder for women to achieve and sustain high levels of fitness. Even the strongest female athlete will have less upper body strength than her male equivalent. To quote a veteran of Afghanistan: “It’s the reason why there are no women in the England Rugby Team.” Or as another serving soldier said: “Women just cannot carry as much kit as men.”

Response: It’s true; women are physically smaller than men and lack the same potential to achieve ultimate physical fitness. This view is supported by the Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. However, as society has begun to treat women equally, allowing them to enjoy more active lifestyles, it is also a fact that they have progressively achieved higher fitness standards. This can be observed not only through the evolution in female body shapes over the last century, but also by the extent to which females have closed the gender gap in performance across different types of sports since 1950. Although female soldiers may not be able to achieve the sheer strength, aggression and ultimate fitness standards of men in elite units, such as the Parachute Regiment and Royal Marines, many thousands of British female soldiers have proved that they can attain very high standards of fitness, including those required by infantry units.

The Army has recently introduced a new Physical Employment Standards (PES) for all ground close combat roles which will come into effect from 2019. It includes new physical fitness standards that are objective, measurable, role-related and gender-free, to ensure Army personnel have the physical capability to meet the necessary force preparation and operational requirements. PES will be incorporated into a new structured suite of Army Role Fitness Tests – a series of tests designed to assess whether personnel are fit for a specific role. Tests include casualty extraction from a vehicle, repeated lift and carry, plus fire and manoeuvre drills. The standards are based on analysis of each role’s requirements, leveraging scientific research conducted by the University of Chichester. Female soldiers who fail the new fitness tests will not be allowed to serve in combat roles. Period.

When it comes to Special Forces units, there is no question of the SAS or SBS lowering their requirements to attract women. Given that 90% of the men that undergo UKSF selection fail, it is extremely unlikely that any female soldier will ever achieve the required standard. Having said that, in January 2013, when the US Army first allowed women to serve in combat roles, a similar view was held about American women entering US Special Forces units. In April 2018, however, it was reported that 12 female soldiers had now graduated from the US Army Ranger School, with applications increasing year-on-year. Female infantry soldiers are also starting to attempt SEAL team selection.

2. Women lack mental strength

Belief: Women do not possess the same mental resilience and resistance to fatigue as men. They are less able to resist cold, interrogation and stress, because they are physiologically and psychologically weaker with less control of their emotions. This means that female soldiers are likely to be less consistent and dependable than male soldiers in tough situations. Or as one ex-soldier put it: “You can’t have a women in your platoon who starts crying as soon as the going gets tough.”

Response: Women serving as SOE agents during the Second World War were in many ways the equivalent of contemporary women serving in combat units. Violette Szabo, Odette Sansom, Lise de Baissac, Noor Inyat Khan and Denise Bloch were all ordinary women who did extraordinary things. Recruited as spies, they received intensive training and were parachuted into France. Performing a number of dangerous missions, they demonstrated remarkable skill, courage and inner strength. Several of these women were unfortunate enough to be captured. They suffered appalling torture and deprivation before meeting horrific deaths, yet they never betrayed their comrades.

We should also remember the nurses, teachers, and ordinary British and Commonwealth housewives who were taken prisoner after the fall of Singapore in 1941. They were forced to march hundreds of miles to prison camps. Their survival depended on them enduring unimaginable hardships over a four-year period, including illness, malnutrition and physical punishment by their captors. Although many died, the vast majority rose to the challenge and showed immense physical and mental resilience. To say that women lack the mental strength of men is to ignore overwhelming historical evidence to the contrary.

3. Risk of Sexual Assault if captured

Belief: Women soldiers who are captured are likely to be subjected to rape.

Response: This risk of female soldiers being sexually assaulted if captured is unfortunately real. However, it is equally a risk for male soldiers. Men are not immune from castration either. According to a retired UK Special Forces officer: “Male soldiers captured in Africa or the Middle East will almost certainly be raped. It happened to soldiers captured in Sierra Leone, Coalition pilots shot down during Operation Desert Storm, and to those who were taken prisoner during Operation Iraqi Freedom. It’s just not talked about.” This is why the Laws of Armed Conflict exist. Those who mis-treat prisoners or non-combatants will be held to account. War remains an ugly business. It’s why we train hard and give our soldiers the best equipment. Being more able to defeat the enemy is the best way to avoid capture.

4. Risk of forming romantic attachments with male colleagues impacting unit cohesion and operational effectiveness

Belief: When men and women are posted to the same unit for extended overseas tours they will naturally form attachments. There may be instances of fraternisation where male and female soldiers have sexual relations with multiple partners within the same chain of command. These may include extra-marital affairs that undermine longstanding relationships with partners back home. In some instances, such episodes may degrade unit cohesion, foster petty rivalries, incite jealousy or feelings of resentment. They can impact unit morale, undermine teamwork and risk reducing operational effectiveness.

Response: When the MoD first proposed opening combat roles to women in 2002, this argument was used to prevent it happening. Subsequent research provided no evidence that the potential problems were insurmountable. The risk of male and female soldiers forming unauthorised attachments is always a possibility. The general rule is that soldiers should not have relationships within the same chain of command. Similarly, relationships between officers and enlisted personnel are frowned upon. This applies to gay male or female soldiers having relationships with members of the same sex within the same units. In most situations good leadership, high personal standards and Army regulations will ensure that conduct is not prejudicial to good order and military discipline. When men and women serve together on operations abroad, even in the most challenging of circumstances, it is wrong to assume that they will automatically cheat on spouses or significant others. When instances of inappropriate behaviour have occurred, e.g. on a nuclear submarine between male naval officer and a female sailor, senior officers have been quick to address the problem. Very often, such occurrences are the result of officers or unit commanders setting a poor example, not other ranks flouting regulations.

Feedback from UK service men and women who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan suggests that the risk of soldiers forming attachments with soldiers in the same unit is a non-issue. Commanders of units with female soldiers attached to them describe their solders’ relationships with them as totally professional and normal. Initially, women attached to infantry units were viewed as a novelty. Once they had proved themselves, they were trusted, treated with respect, and became valuable members of the team Gender became irrelevant. It was about the person and personal qualities they brought to the role, not whether they were male or female.

One aspect of this concern is that many serving male soldiers in infantry and cavalry regiments are simply not used to working with female soldiers. Once the wider integration of female soldiers into combat units has taken place, the concept of women in combat should become normalised.

5. It is a natural male reaction to be protective towards women

Belief: Male soldiers will prioritise female safety or prioritise female casualties above male ones, which could potentially compromise mission success.

Response: Natural male protectiveness towards women is also a case of stereotyped male attitudes. When British Army units have deployed mixed units in combat, feedback unequivocally asserts that the mission always came first. Any suggestion that the presence of female soldiers in a dismounted infantry unit caused normal standard operating procedures (SOPs) to break down suggests that any such units where this might occur would have very low standards of discipline and training.

6. Mixed gender units are less effective than all male ones

Belief: All male units will be more effective in combat than units comprised of men and women.

Response: If men are ultimately bigger, fitter and stronger than women, it follows that a combat unit comprised of men will be more effective. But this views assumes a very narrow definition of combat. If a deployment only involves long-distance patrolling over challenging terrain, closing with and engaging the enemy in highly physical hand-to-hand combat, then you need the fittest, meanest, most aggressive soldiers you can find.

Increasingly, however, combat is not about hand-to-hand fighting. It is operating combat vehicles or sophisticated weapon systems many kilometres away from the enemy. It may include piloting drone aircraft from secure bases or launching missiles hundreds of miles from the front line. In such circumstances, the ability of a female soldier to kill the enemy with her bare hands or to yomp carrying her own bodyweight in kit will be less important. What will matter is technical proficiency to operate highly sophisticated weapon systems.

Sniping is a good example of frontline combat roles where women can outperform their male counterparts. Would a male sniper be preferable to a female one if he was less competent? After all, even the strongest male combatant is vulnerable to a bullet fired by a women as he is to one fired by a man.

Again, mission effectiveness is about balancing the task, the team and the individual. It is not about gender but the quality of skills each soldier brings. For these reasons, generalisations that assert mixed teams are better than all-male teams are misguided. Team composition will depend on the task. Ultimately, you just want the best people for the job in hand.

___________________________________

So what?

There are genuine challenges connected to opening ground combat roles to women in the British Army. The process of integrating them will not be easy. There will be problems. But, on balance, maybe the pay-off will be worth the effort?

Today, we don’t think twice about female police officers. The way in which women PCs have been integrated into UK Police Forces across the Country has been a universal success. Though women PCs who are less strong than their male peers have struggled to apprehend violent criminals and hooligans, technology is on their side. Tasers, pistols and communication systems that allow female officers to call for back-up rapidly have been great equalisers. Above all, by allowing women to serve on the frontline, UK Police have benefitted by being able to access a larger pool of talent.

These advantages translate directly to female soldiers in the British Army. Having women in support roles has already made it easier to staff important technical roles. Allowing women to serve in combat roles now normalises the integration of women in the infantry and cavalry regiments. Trained soldiers, male or female, can now be allocated to units as the need for their particular skills arises. It means that seeing women in Guards or Rifles regiments will be as common as seeing them in RLC or AGC units. If we’re going to have equal opportunities for all, then this is how it should be.

Above all, women in the armed forces should not be the shocking phenomena that some perceive it to be. It was during the Crimean War (1853-1856) that Florence Nightingale and her team of female nurses revolutionised the care of injured combatants. Her spartan field hospital was located uncomfortably close to the frontline. British nurses endured terrible conditions and were exposed to a multitude of dangers.

During the First World War, women again served as nurses as well as in other support roles. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, some 655 women were killed during the conflict. In the Second World War, British Government records show that 640,000 women served in non-combat roles. Even Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II trained as a mechanic in the Auxiliary Territorial Service. Female roles included pilots, ambulance drivers, clerks, mechanics and nurses. Again, many thousands paid the ultimate price for their service.

During the Vietnam War, 11,000 women served in the US Army. In 1991, 28,000 American women served during Operation Desert Storm. Today, the US Armed Forces is comprised of some 350,000 women or 16% of its total personnel. With the US Army and US Marine Corps allowing women to serve in combat units from 2013, it seemed only natural that the UK should also allow them to serve widely and in any role they wish. History shows that women soldiers have succeeded in every task they have been required to perform.

During the British Army’s most recent deployments, to Iraq and Afghanistan, women begun to be employed in combat roles. Charlotte Madison (a Pseudonym) and Joanna Gordon became the UK’s first Apache helicopter pilots. Madison’s book, Dressed to Kill, which recalls her three tours of Helmand Province, busts any myths about women being given special treatment. Her three tours of Afghanistan resulted in her killing more enemy combatants than Harold Shipman, Jack the Ripper and Myra Hindley put together. Women also served on the frontline as combat medics. Joining dismounted infantry on extended patrols, they were required to carry the same heavy loads as the men. With many female soldiers weighing less than their male counterparts, they carried a much higher percentage of their total body weight in weapons, body armour and equipment.

It goes without saying that British Army combat load burdens are too high and impact the ability of both male and female soldiers to be effective on the ground. As a distinguished American general recently said: “soldiers can be pack animals or warriors; they just can’t be both at the same time.” While male soldiers were naturally expected to manage the weight of their equipment, what surprised many senior officers was how well female soldiers coped with heavy loads over arduous terrain. Strength and fitness were not the issues that commanders imagined they would be. This is not to say that there were no times when female soldiers struggled. But male soldiers also suffered from carrying excessive weight.

Far from being squeamish, female combat medics coped with violent and stressful situations to administer life-saving first-aid to those who needed it. Above all, when the situation arose, women never hesitated to use their personal weapons to eliminate enemy threats. Deployed to Afghanistan in 2011, Medic Chantelle Taylor, was in a convoy that was ambushed by the Taliban. She found herself face-to-face with an enemy insurgent. It was a kill-or-be-killed moment. Taylor’s instinct for survival prevailed. As far as she was concerned, she was just doing her job – just like the men in her unit.

Captain Lisa Head, was bomb disposal officer in Afghanistan in 2011. Supporting 2nd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, she was killed when she attempted to defuse an IED that had been deliberately rigged to kill anyone who tried to disarm it. Captain Head was one of only a few EOD personnel to achieve “High Threat IED Operators” status. She is remembered with great respect not because she was a women, but because she was professional, courageous and skilled at her job.

Private Michelle “Chuck” Norris served as a combat medic attached to The Queen’s Royal Hussars Battle Group in Al Amarah, Southern Iraq in 2006. She was just 19-years old and had only recently completed her training. Travelling in the back of a Warrior IFV that came under fire, the vehicle commander was shot in the face by a sniper. Private Norris immediately jumped out of the back of the vehicle, and despite being just 5ft tall, managed to drag C/Sgt Ian Page out of the vehicle turret. As she was doing this, she came under fire from several different positions, with bullets ripping into her rucksack. As soon as the casualty was safe, she began to administer first-aid that saved his life. She became the first female soldier to be awarded the Military Cross.

In each of the situations described above, the women involved were attached to frontline combat units. They did not compromise unit discipline, operational effectiveness or morale. The men with whom they served universally considered these female soldiers as their equal.

Despite the Army opening all roles to women, it is unlikely that female soldiers will rush to join infantry and cavalry regiments or attempt SAS selection. Instead, most can be expected to continue to find niche roles in support units that are well suited to their abilities. But, occasionally, women will be called upon to fight or to provide specialist skills in the direct fire zone. We need to acknowledge that when properly trained, British female soldiers will be more than up to the task.

Saying that women don’t belong in combat roles is the same as saying women have no place in the boardroom, in politics or in the police. History shows us that women have frequently overcome entrenched views by proving themselves in every role they have been allowed perform. Indeed, it could be said that the only barrier to wider female achievement in military roles has been male gender bias that subjectively decided what women should and shouldn’t do, rather than objective analysis what they could and couldn’t do. But this discussion is not about the battle of the sexes; it’s about making the British Army as professional and competent as it can be.

Opening all combat roles may not change the composition of the Army. But it may change the Army’s attitude to women, placing greater confidence in their abilities, treating them as equals and empowering them to be all that they can be. The return on this investment will be a more united, integrated force better able to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow.

Well that is disappointing to say the least. A reasoned response to this article was posted yesterday and appears to have been ‘disappeared’ today.

LikeLike

Bill, Comment were disabled as the topic was generating too much polarised opinion. I need to rewrite this and will then open it up for comments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apparently this article is far less controversial than your C2 Life Extension Program article…. Interesting. It is as it should be IMO, a non-issue, as anyone who meets the set standards is qualified.

LikeLike

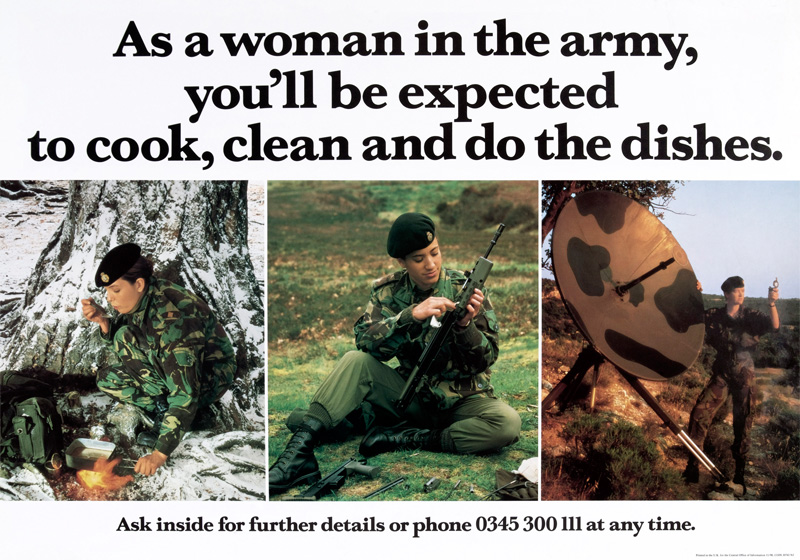

Women soldiers just look cringy. That says a lot.

Call it “intuition in ethics,” or whatever, but the elephant in the room is that pretty much anyone looks at pictures like in this article and just wants to wince a little (or a lot).

Little children are more honest about things like this, because they are apolitical: a group of boys will laugh at the boy in the group who can’t throw the ball, can’t throw the ball as far, or whatever, and say “he’s [doing whatever] like a girl”; but fast forward some years when everyone is an adult, and the politics comes into play.

If the emperor has no clothes, he’s naked, simple as that. If people felt they could say what they *really* think, *when they need to say it*, there wouldn’t be so much oohs and awes at the idea of female soldiery.

The industrialized world, particualry Europe and the U.S.A., is already facing a major demographic problem. Not as bad as, say, China, but bad nonetheless. Women have babies. They are literally made to have babies. But somewhere along the line, most people apparently “forgot” that.

This is a prime example of people getting ‘too smart for their own good’, with increasing societal complexity: societies that can send rovers to Mars and build mile long suspension bridges, but can’t see that there are male and female, that there is dimorphism, and that this hints at a difference in evolutionary development, physically, emotionally, psychologically, epigenetically, etc.

LikeLike